This is a talk delivered by Sarah Phillimore at the Families Need Fathers conference in London on September 14th 2019

The abstract concept of ‘Justice’ is often portrayed as the Greek goddess Themis, usually depicted holding a sword and scales. This represents her ability to cut fact from fiction with no middle ground and the need to be balanced and pragmatic. However the blindfold is a modern addition. It symbolises that justice must be blind i.e. applied equally to all who come before her.

In recent years there appears to have been an orchestrated campaign against both the scales and the blindfold, when it comes to issues of violence in intimate relationships before the family courts. For the first time in my 20 years now as a lawyer, I see not merely journalists and campaigners showcasing their lack of understanding of law and procedure – I see them joined and supported by actual politicians and actual ‘Inquiries’ established by actual Government departments. I and others have commented critically about this elsewhere

If this sounds harsh I am sorry. I do not say this to diminish the suffering of victims of abuse. Violence in relationships is common and is a blight on our society. I agree that a parent who is abusive to anyone, let alone their child’s other parent, is not a good parent and they should not have unfettered access to a child without some clear evidence that this is safe. I agree that women are more likely to be the victims of violence at the hands of male partners. Further, I would be surprised to find anyone who doesn’t think it outrageous that people risk being cross examined directly by those who may be using the court system to further abuse and humiliate. Happily, in my experience at least this is not commonplace – Just out of interest – how many people in this room have either questioned directly an ex partner in court or been questioned directly by an ex partner?

We must be able to say the names of those children who have died painful and frightening deaths at the hands of their adult carers, when the child protection system failed to ask the right questions or properly assess risk – Ellie Butler, Alexa-Marie Quinn, Peter Connelly, Victoria Climbie, Elsie Scully-Hicks Daniel Pelka

Even this short list is too long. When the child protection system fails it is their faces that we must see.

But. It is clear that children risk being hurt and killed by men AND women. Even in that short list above shows women are capable of hurting and killing children, or of deliberately lying to protect the men they know are hurting them.

The only fool proof way to prevent children from pain and suffering is to prevent them from ever being born. There is no system that can protect against all risk. We need to do better – and I will discuss today how we can do that – but the answer to a system that you find unsatisfactory and potentially unfair is NOT to agitate to make it even more unsatisfactory and unfair.

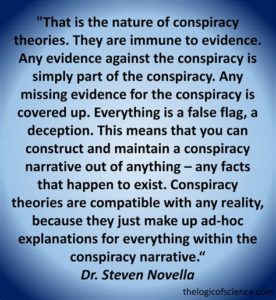

I don’t agree the current crop of campaigners will achieve anything to make victims and their children safer. The MoJ Inquiry and the Sunday Mirror ‘campaign’ etc etc etc is a call to examine or change laws which do not actually exist. I am repeatedly told via social media that we ‘must’ see a change to the law that permits ‘snap decisions which promote contact at all costs’. This is not, never has been and never will be the law.

To campaign on such a false premise is a waste of time and energy. More sinisterly, the ‘changes’ which people want to see, appear to involve very significant challenge to the integrity of both the rule of law and due process.

- by describing complainants as ‘victims’ at the very outset.

- Assuming that these ‘victims’ are women

- By inviting under the campaigning umbrella a number of women who have been found to have caused very serious harm to their children, yet rejecting those findings as yet more ‘failings’ of the family courts. [For comment on Victoria Haigh and the very many judgments against her, see this post from The Transparency Project. ]

https://twitter.com/SVPhillimore/status/1168140277468545030?s=20

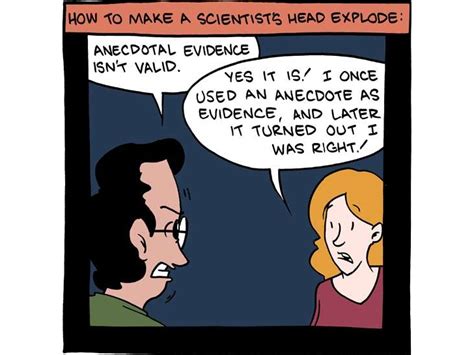

I believe Brexit has unleashed something very harmful into our attempts to talk about serious issues; experts are disdained, facts are distorted and feelings are what matter. This joined forces with another trend – the identification of ‘complainants’ as ‘victims’ before any allegation is either accepted as true or found to be so. This first emerged in the criminal justice system; tragically as a very well intentioned effort to combat some of the truly disgusting treatment meted out by police and lawyers to those who complained about sexual assault.

However, the law of unintended consequences continues to operate, and as Richard Henriques warned and the the trial of Carl Beech showed, to designate people as ‘victims’ at the very outset of any investigative procedure, has the potential to cause serious and damaging consequences for the integrity of what follows.

The time has long gone for those of us who are deeply troubled by all of this to attempt to reclaim the narrative, to restore the position that words have meaning. They are important. Because language shapes thought – not the other way around.

There are two fundamental and serious problems in using the word ‘victim’ to describe a complainant whose allegations have either not been proved or have not been accepted. It is unfair to all who participate in court proceedings.

- setting up a complainant as a ‘victim’ at the inception of the court process gives that person a wholly unrealistic view of how their evidence may be treated in an adversarial court process. It is not enough to simply assert something – you must prove it.

- Treating one party as a victim prior to any findings made about the factual basis for that status, risks undermining the fairness of the proceedings and casting the respondent as a ‘villain’ at the outset.

So I will attempt today to go back to basics.

- What is the rule of law? What is ‘due process’? And why are they important?

- What is evidence? And how does the family court use it? How should you present it?

- Where is the system failing and what can we do to make it better?

What do we mean by the ‘rule of law’ and ‘due process’ ?

The Secretary-General of the United Nations defined the rule of law in this way:

a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards. It requires, as well, measures to ensure adherence to the principles of supremacy of law, equality before the law, accountability to the law, fairness in the application of the law, separation of powers, participation in decision-making, legal certainty, avoidance of arbitrariness and procedural and legal transparency.” (Report of the Secretary-General: The rule of law and transitional justice in conflict and post-conflict societies (S/2004/616).

The rule of law is one of six of the key Worldwide Governance Indicators (The others being Voice & Accountability, Political Stability and Lack of Violence, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, and Control of Corruption).

‘Due process’ is under the umbrella of the Rule of Law:

- procedural due process – legal proceedings which are carried out in accordance with established rules and principles; and

- substantive due process – legal proceedings should not result in the unfair, arbitrary or unreasonable treatment of an individual.

If you are in any doubt as to the importance of the ‘rule of law’ or due process, visit and spend some time in one of the countries which doesn’t have either.

So what IS evidence? And how does the court treat it?

I make no apology for going back to basics, such is the staggering level of misinformation I am seeing on a daily basis from those who purport to have positions of authority and credibility.

Evidence is anything that you experience, read or are told that causes you to believe something happened. It is the information used in court to try and prove something. It can be obtained from documents, objects or witnesses.

Establishing the evidence in a case allows you to ask ‘what does it prove?’. A thing that is proved or accepted then becomes a fact which is relevant to the outcome of the case. We need to know the facts in order to decide what consequences follow or what the risks are and how they are to be managed. The Family Justice System (FJS) puts proof of facts at its heart.

In 2013 Mr Justice Baker addressed a conference asking – how can we improve decision making in the family courts? He identified the twin evils of delay and cost which impact on the quality of decisions made. He commented on the alternatives to litigation, such as mediation or arbitration that might work to mitigate those evils. But he was also clear that alternatives to litigation could never be complete substitutes for litigation.

But there will always be a substantial number of disputes in which a forensic process is unavoidable, a process that involves consideration of allegations and cross-allegations made by the parties, a judicial analysis of the evidence, the makings of findings and an assessment of the consequences of those findings. There are some people who genuinely believe this can be done by some sort of committee without involving lawyers at all. Such views are profoundly mistaken.

This does not mean of course that our current system is without flaws. ‘Fact finding’ may sound simple but is anything but. The foocus on most law degrees is dissection of the lofty legal decisions of the superior courts – but when they hit the ground in practice, the vast majority of legal endeavours will involve the identification and processing of facts.

Understanding how to identify and apply facts in court is complicated. Jerome Micheal, the author of ‘The nature of judicial proof: An inquiry into the logical, legal, and empirical aspects of the law of evidence’ summarised his view of the ‘theoretical basis of the arts of controversy’ in 1948, pointing out that there are very many things we need to appreciate when we approach evidence in a court. Among others, we need to understand probability, causation, the distinction between direct or perceptual and indirect or inferential knowledge. We base much of our understanding on presuppositions about human nature and behaviour – these often change over time or as research develops – but we need some basic knowledge about how humans think and react.

Judges often say findings of fact must be based on evidence, not speculation – Re A (A Child) (Fact Finding Hearing: Speculation) [2011] EWCA Civ 12) but as that case illustrates, the line between the two is not always clear or easy to find and obviously involves some subjective discretion form the decision maker.

However, regardless of all the obvious imperfections of the fact finding exercise, we have as yet, no other system to deal with contested allegations. I am not sure what else could be suggested – we return to trial by combat? Or in the modern era presumably this will be ‘trial by Facebook’ – whoever can garner the most ‘likes’ and ‘shares’ or the biggest amount in their crowd funder will ‘win’. I have a horrible suspicion that this is exactly how some people think it should work, as we have seen in both the Minnock and Baldwin cases.

But unless and until Parliament decides to dissolve the courts of law in favour of the courts of public opinion, we need to focus on what we have got.

The family court process

Deciding what ‘weight’ attaches to the evidence will comprise a mixture of objective and subjective elements. Judges have a pretty wide discretion; it is not a ground of appeal that you didn’t agree with the judge’s decision. You have to show the judge was wrong – he or she took into account the wrong things or ignored the right things. Just because a Judge fails to explicitly mention a particular point, doesn’t mean the appeal court will allow your challenge to succeed. A useful example of this can be found in the case of A and R (Children), Re [2018] EWHC 2771 (Fam) where the Recorder was criticised for not making explicit reference to some parts of PD 12J.

Family courts operate an ‘adversarial’ as opposed to ‘inquisitorial’ system. This means that the Judge can only decide the case that is in front of him or her. The Judge does not take on an investigative role. Evidence is presented to the court and challenged by the parties as ‘adversaries’ in the court process. Claims that we are in fact ‘quasi-inquisitorial’ seems to mean in practice to amount to little more but that lawyers are asked to tone down their combativeness a notch.

The court must take into account all the pieces of evidence in the context of all other evidence, The civil standard of proof applies, which means facts must be proved ‘on the balance of probabilities’: If it is more likely than not that the thing happened it is proved – see Re B [2008] UKHL 35). This is known as the ‘binary system’ as there are only two options – true or false. I appreciate that there is legitimate criticism of this, particularly given the low standard of proof and again I would like to see more official recognition of this, rather than the predominant congratulatory back slapping that the family courts have ‘discovered the truth’.

Over time rules of evidence developed, to attempt to make proceedings as consistent and fair as possible. For example, in most civil cases ‘hearsay evidence’ is not permitted – that is the evidence of those who tell the court, not what they know themselves, but what they have heard from others. A fundamental point of fairness is that if you don’t accept the evidence offered against you, you must have the ability to challenge it. Its obviously very difficult to challenge the words of someone not in court. For this reason if hearsay is accepted in family court proceedings, the judge must think very carefully about the weight to be attached to it.

Expert Evidence

A particular bone of contention revolves around the use of experts – as these experts are often in the ‘soft science’ field of psychology. I accept that the use of experts is not without controversy and I have seen a worrying lack of humility from some about the strength of their conclusions. However, it’s important to remember that ‘the expert advises but the court decides’ . Expert evidence is just one piece of a jigsaw that a judge needs to try and put together – it is rarely the entire answer to the case – see Re T [2004] 2 FLR 838.

As Professor Luthert commented in R v Harris and Others [2005] EWCA Crim 1980: It is very easy to try and fill those areas of ignorance with what we know, but I think it is very important to accept that we do not necessarily have a sufficient understanding to explain every case.

A judge does not have to accept an expert’s evidence but must explain why the evidence is not accepted. See the comments of Lord Justice Ward and Lady Justice Butler-Sloss in the case of Re B (Care: Expert Witnesses) [1996] 1 FLR 667

I accept we need a greater awareness of and willingness to challenge experts on the basis of confirmation bias or scientific prejudice but as barrister David Beddingfield comemented in 2013 – this can be tricky – see Expert Evidence – Another Chapter in a Continuing Story in Family Law Week:

The expert, as we all know, is expected to give an opinion about the most significant issues in a case. A paradox underlies the use of all expert evidence: the reason an expert is required is that the decision-maker lacks the expertise of the expert and requires that expert’s help. How is that same decision-maker also competent tojudge the content of the expert’s evidence? How is the decision-maker to choose, for example between two competing experts, each using different methodologies beyond the ken of any non-specialist?

Practical problems in family cases – Documents versus words

The uncontroversial ‘gold standard’ of evidence is the contemporaneous documentary record. And this is the fundamental reason why allegations about what did or did not happen in intimate relationships can be so difficult to prove in court, even on a low standard of proof. Many cases I have dealt with involve a bitterly fought battle between parents who make allegations each against the other which are starkly different. It is difficult to discern patterns of behaviour and very difficult to cross examine on a bare denial.

Relationships, which may have endured over decades, may offer the court little evidence but the words of the parties themselves. Not many of us – I hope – enter into a relationship expecting to keep a running log of all the bad behaviour of our partners.

I was asked a very interesting question about this issue of ‘collecting evidence’

…. would it help to suggest that people keep diaries, records, photos, dates, times, places – particularly when there are already difficulties i.e. any statements may be seen to be more credible if they are detailed and based on contemporaneous notes?

And my answer to that is ‘be careful’. You do run a risk that you may appear to be offering self serving or manipulated evidence. The courts are often very wary of recordings of arguments etc because of course it is difficult to know what happened immediately before the recording started. I have seen recordings and diary entries used with powerful effect but there is always a suspicion that such one party may have acted deliberately to antagonise the other in order to ‘collect evidence’ . I appreciate this is a very difficult position to be in – much abuse occurs behind closed doors and the abuser is able to present a very different face to those outside the relationship.

But it remains an inescapable truth that the more serious the allegations you make, the less likely is any court to simply accept them, absent any supporting evidence – see for example the case of Sivasubramaniam v Wandsworth County Court & Ors [2002] EWCA Civ 1738. The complainant described events to the court in this way:

… part of a long-running criminal conspiracy against him involving members of Wandsworth Borough Council solicitors, lawyers and the chief executive and the finance officer and their assistants, members of the Wandsworth police, doctors in the hospitals, social workers, local court officials, judges and the lessee occupying the flat below his. The conspiracy involved unsuccessful attempts to murder him … It had included impersonation of him, had involved the fraudulent termination of four sets of legal proceedings that he was conducting, including the two with which we are concerned, while he was detained under the Mental Health Act or under medication thereafter, and continued to this day.

Unsurprisingly the court declared that no Judge would be able to accept such a version of events on one person’s word alone.

Gold Standard Evidence versus Witness Credibility

The courts have said for a long time that the best way of testing witness credibility is to test witnesses against objective facts which are independent of their testimony.

Lord Goff in Armagas Ltd v. Mundogas S.A. (The Ocean Frost), [1985] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 1, p. 57:

Speaking from my own experience, I have found it essential in cases of fraud, when considering the credibility of witnesses, always to test their veracity by reference to the objective facts proved independently of their testimony, in particular by reference to the documents in the case, and also to pay particular regard to their motives and to the overall probabilities. It is frequently very difficult to tell whether a witness is telling the truth or not; and where there is a conflict of evidence such as there was in the present case, reference to the objective facts and documents, to the witnesses’ motives, and to the overall probabilities, can be of very great assistance to a Judge in ascertaining the truth.

Lord Pearce in the House of Lords in Onassis v Vergottis [1968] 2 Lloyds Rep 403 at p 431:

Witnesses, especially those who are emotional, who think that they are morally in the right, tend very easily and unconsciously to conjure up a legal right that did not exist. It is a truism, often used in accident cases, that with every day that passes the memory becomes fainter and the imagination becomes more active. For that reason a witness, however honest, rarely persuades a Judge that his present recollection is preferable to that which was taken down in writing immediately after the accident occurred.

It is clear that people who have been traumatised by abuse over many years can behave in ways that reflect that trauma. They may not be able to be clear or consistent in their account. They may have been too afraid or too ashamed to have told any one else so have no police or medical evidence. Or they may worry about ‘rocking the boat’ and risking losing contact with their children. Exposure to gradually escalating abuse and intimidation can become numbing and appear ‘normal’ – the ‘boiling a frog’ principle.

The massive problem for the court system however is that a tendency to be inconsistent or reveal crucial details at a much later stage is also strongly suggestive of someone who is lying.

Therefore the credibility of witnesses in family cases is often of supreme importance. It really matters how you come across when you give evidence. The appeal courts often say that they are at a disadvantage when examining a challenge to the decision of the first court, as they don’t have the same opportunity to assess how people gave their evidence as well as what they actually said. I think there is a danger – of which the courts are aware – that too much or improper weight can be put on demeanour as an indication of credibility. They are two very different things – ‘demeanour’ is concerned with whether or not a witness appears to be telling the truth.

It is usually unreliable and often dangerous to draw conclusions from demeanour alone. Is someone hesitant because they are lying or just naturally cautious? These problems are magnified where the witness is from a different country or culture than the Judge or is giving evidence through an interpreter. I accept that most of us still do have a view of how a ‘victim’ should present in court – particularly if that alleged victim is female, and I accept there is a risk that people who don’t fit the general stereotype of ‘victim’ – i.e. weak, timid, tearful – may find their accounts treated as less credible.

The case of Excelerate Technology v Cumberbatch [2015] provides some useful discussion about how Judges assess credibility. It is determined by looking at the following issues.

- is the witness a truthful or untruthful person?

- If truthful, is he telling something less than the truth on this issue?

- if untruthful is he telling the truth on this issue? Not all liars lie all the time and motivations for lying can vary; see the Lucas direction.

- If truthful and telling the truth as he sees it, can his memory be relied upon?

- Is what is asserted so improbable that it is on balance more likely than not he was mistaken in his recollection?

What can we do to improve the situation?

So – what do we do? I accept that court arenas are unpleasant places at the best of times. Attempting to establish the truth or otherwise of your experiences in an abusive relationship is very far from the best of times.

The lawyers and judges must have a clear understanding of how to make proceedings as fair and efficient as possible:

- have clear understanding of the requirements of PD 12J – see below.

- Be wary of making any decision based on the demeanour of a witness or what a victim ‘ought’ to do

- make sure vulnerable witnesses have a safe place to sit and wait before the hearing starts

- make sure that issues of screens in court, video links and intermediaries are properly discussed in good time.

- be more willing to impose serious penalties on those who are found to have lied in their evidence

- list findings of fact as soon as possible and be prepared to take enforcement action as soon as it becomes clear the resident parent won’t accept the findings of the court

What will help the parties?

- Understand the court process

- Understand the burden and standard of proof

- where ever you can – find some additional evidence that supports what you are saying. Are there any medical records or police reports? Did you say anything to a friend or family member at the time? Would they be willing to come to court and be cross examined about what you said?

- If you have nothing other than your words – that is still evidence but you must be careful to be as clear and consistent as you can. Set out your statement in short numbered paragraphs and go in chronological order. Include everything that you can remember.

However, it has been my view for some time that the fundamental challenges to fair, efficient and humane processing of legal complaints about violence in intimate relationships are very little to do with the lawyers, the Judges and their lack of understanding or training. The real problems will require political will and a huge amount of cash to sort out.

- court buildings that are not fit for purpose – no or very few waiting rooms, no separate entrance, courts sitting in cramped rooms with very little space, inadequate technology to accommodate video links etc

- lack of judges and available court rooms to hear fact findings quickly – cases quickly become stuck and are allowed to drift.

- lack of judicial continuity which is detrimental to effective case management – see comments in the case of A and R (Children), Re [2018] EWHC 2771 (Fam) para 57 -61.

- lack of legal aid so that vulnerable witnesses may have be face being cross examined by their alleged abuser, the issues in the case are not identified and presented efficiently, litigants in person can’t afford to instruct experts etc, etc, etc.

- wider societal problems, such as lack of available safe and affordable housing so that the financially weaker partner finds it very difficult to leave an abusive relationship particularly if there are children involved.

This is what we need to tackle. And I have to wonder why we are all so keen to be distracted by yet another newspaper campaign based on what seems to be a complete lack of knowledge or understanding of any of the issues I raise above. At the moment, the only people I can see who will benefit from all this are those who are pushing for Judges to be ‘trained’ – presumably by their own organisations and at significant cost.

And a the elephant in the room will remain. Why do so many people behave so badly in intimate relationships? And why do so many people have so little self worth that they accept it or cannot recognise it until many years have passed and great harm has been done? What as a society are we going to do about this? is there anything ‘we’ can do?

All I can say with certainty is that continued insistence on the FJS or any external agency to ‘fix’ the problems of cruel, unreasonable or otherwise dysfunctional people is doomed to expensive and emotionally harmful failure. And those who will suffer most, as they always do, are the children.

APPENDIX

Definitions in Practice Direction 12 J

Domestic abuse” includes any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality. This can encompass, but is not limited to, psychological, physical, sexual, financial, or emotional abuse. Domestic abuse also includes culturally specific forms of abuse including, but not limited to, forced marriage, honour-based violence, dowry-related abuse and transnational marriage abandonment;

“coercive behaviour” means an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten the victim;

“controlling behaviour” means an act or pattern of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour;

“development” means physical, intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development;

“harm” means ill-treatment or the impairment of health or development including, for example, impairment suffered from seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another, by domestic abuse or otherwise;

“health” means physical or mental health;

“ill-treatment” includes sexual abuse and forms of ill-treatment which are not physical

Para 5 what must the court do?

- dentify at the earliest opportunity (usually at the FHDRA) the factual and welfare issues involved;

- consider the nature of any allegation, admission or evidence of domestic abuse, and the extent to which it would be likely to be relevant in deciding whether to make a child arrangements order and, if so, in what terms;

- give directions to enable contested relevant factual and welfare issues to be tried as soon as possible and fairly;

- ensure that where domestic abuse is admitted or proven, any child arrangements order in place protects the safety and wellbeing of the child and the parent with whom the child is living, and does not expose either of them to the risk of further harm; and

- ensure that any interim child arrangements order (i.e. considered by the court before determination of the facts, and in the absence of admission) is only made having followed the guidance in paragraphs 25–27 below.

In particular, the court must be satisfied that any contact ordered with a parent who has perpetrated domestic abuse does not expose the child and/or other parent to the risk of harm and is in the best interests of the child.

Para 8

In considering, on an application for a child arrangements order by consent, whether there is any risk of harm to the child, the court must consider all the evidence and information available. The court may direct a report under Section 7 of the Children Act 1989 to be provided either orally or in writing, before it makes its decision; in such a case, the court must ask for information about any advice given by the officer preparing the report to the parties and whether they, or the child, have been referred to any other agency, including local authority children’s services. If the report is not in writing, the court must make a note of its substance on the court file and a summary of the same shall be set out in a Schedule to the relevant order.

How do we deal with tension around open justice and protecting the vulnerable? Para 10:

If at any stage the court is advised by any party (in the application form, or otherwise), by Cafcass or CAFCASS Cymru or otherwise that there is a need for special arrangements to protect the party or child attending any hearing, the court must ensure so far as practicable that appropriate arrangements are made for the hearing (including the waiting arrangements at court prior to the hearing, and arrangements for entering and exiting the court building) and for all subsequent hearings in the case, unless it is advised and considers that these are no longer necessary. Where practicable, the court should enquire of the alleged victim of domestic abuse how best she/he wishes to participate.

Why are fact findings important – para 16

The court should determine as soon as possible whether it is necessary to conduct a fact-finding hearing in relation to any disputed allegation of domestic abuse –

(a) in order to provide a factual basis for any welfare report or for assessment of the factors set out in paragraphs 36 and 37 below;

(b) in order to provide a basis for an accurate assessment of risk;

(c) before it can consider any final welfare-based order(s) in relation to child arrangements; or

(d) before it considers the need for a domestic abuse-related Activity (such as a Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programme (DVPP)).

Para 40 In its judgment or reasons the court should always make clear how its findings on the issue of domestic abuse have influenced its decision on the issue of arrangements for the child. In particular, where the court has found domestic abuse proved but nonetheless makes an order which results in the child having future contact with the perpetrator of domestic abuse, the court must always explain, whether by way of reference to the welfare check-list, the factors in paragraphs 36 and 37 or otherwise, why it takes the view that the order which it has made will not expose the child to the risk of harm and is beneficial for the child.