This is a post by Sarah Phillimore.

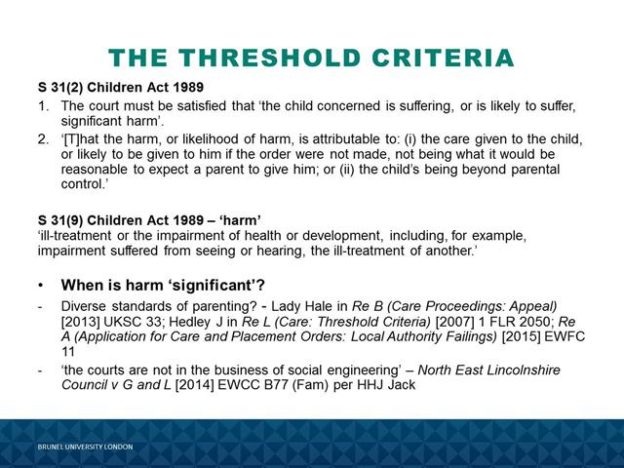

You will often hear the phrase ‘threshold criteria’ or ‘threshold analysis’ being used in care proceedings but unsurprisingly, anyone who isn’t a lawyer or social worker, often doesn’t understand what it means. In summary, the ‘threshold criteria’ are the facts that a local authority have to prove if they want the court to make a care order or a supervision order.

The ‘Two Stage’ Test in care proceedings

In order to justify making a care or supervision order, the court has to satisfy a two stage test:

The first stage – the threshold stage – there must be sufficient reasons to justify making a care or supervision order – or in other words, the case must cross a threshold. This threshold can only be crossed if the court agrees:

- that things have happened which have already caused significant harm to a child,

- or pose a serious risk that significant harm will be suffered in the future,

- or which show that the child is beyond parental control.

If the child is not suffering or at risk of suffering significant harm there CANNOT be a care or supervision order. This is because the requirements of section 31(2) of the Children Act 1989 will not be met.

The second stage – the welfare stage – even if the threshold is crossed, it must be in the child’s best interests to make an order. It is not inevitable that a care order will be made every time a child has suffered significant harm (but it is likely).

The importance of the ‘threshold criteria’

If you don’t cross the threshold, the court can’t make a care or supervision order. Therefore, the relevant facts must be proved on the balance of probabilities. If this isn’t done, the care proceedings have to stop. It is therefore vital to establish at a very early stage exactly what the LA want to rely on as their threshold criteria and to find out if the parents will agree or there needs to be a court hearing to test the local authority’s evidence.

The local authority will have to prove that things happened on or before the date they applied for a care or supervision order. It can rely on information that became available after that date, as long as it is information relevant to what was happening at that time. See R G (Care Proceedings: Threshold Conditions) [2001].

How is significant harm caused?

- EITHER by what the parents are doing or failing to do for their children (i.e. its more likely to be perceived as ‘their fault’)

- OR because the child is beyond parental control (which may not necessarily be considered the parents’ fault).

See the case of WBC v A [2016] EWFC B70 in October 2016 where the court decided that there was no need to try and link a child being beyond parental control with anything that was the parents’ ‘fault’ – therefore threshold could be met on that basis without any need to ‘blame’ the parents.

However, whether or not the parents are to ‘blame’ for what has happened to the children, there must be a clear link between the significant harm and the events on which the LA rely.

Lady Hale in the case of Re J [2013] UKSC 9 said:

Time and again, the cases have stressed that the threshold conditions are there to protect both the child and his family from unwarranted interference by the state. There must be a clearly established objective basis for such interference. Without it, there would be no “pressing social need” for the state to interfere in the family life enjoyed by the child and his parents which is protected by article 8 of the ECHR. Reasonable suspicion is a sufficient basis for the authorities to investigate and even to take interim protective measures, but it cannot be a sufficient basis for the long term intervention, frequently involving permanent placement outside the family, which is entailed in a care order.

What should the ‘threshold’ document contain? And when will I see it?

The local authority have to set out the proposed threshold in the application form for a care or supervision order. Some commentators have expressed concern that sometimes local authorities are not very good at setting this out clearly. See this post from Pink Tape. But hopefully parents will be able to get at least some idea of the case against them at the earliest stage.

Documents setting out the threshold criteria are meant to be quite short but will need to have enough detail to justify the proceedings and so the parents understand the case against them. The local authority will provide further evidence to support their threshold criteria with statements from social workers and other professionals such as teachers or doctors, depending on the facts of the particular case in front of them. But the threshold document should act as a clear and accessible summary of the problems and provide a quick ‘way in’ to understanding what the case is all about.

Sir James Munby, when President of the Family Division, discussed the format and length of the ‘threshold statement’ that a local authority must provide in 2013. (View from the President’s Chambers: the process of reform: the revised PLO and the local authority [2013] Fam Law 680). He states that the threshold document should be limited to no more than 2 pages and that the court does not need to find ‘a mass’ of specific facts to determine that threshold is crossed. In asking the question – what does the court need? he answers:

It needs to know what the nature of the local authority case is; what the essential factual basis of the case is; what the evidence is upon which the local authority relies to establish its case; what the local authority is asking the court, and why.

The Court of Appeal endorsed this view in the case of Re J (A Child) [2015] and further endorsed the crucial importance of linking the facts relied upon with the requirements of section 31 of the Children Act 1989, which the President further discussed in the case of Re A (A Child) [2015].

Linking the alleged facts to the harm suffered, or likely to be suffered.

For example: the LA might say:

‘The child has suffered significant emotional harm evidenced by:

- frequent exposure to his parents arguing and fighting while he is present in the family home;

- On at least two occasions in the past year the police were called by concerned neighbours when the parents were fighting (see police reports at pages XX of the bundle);

- The police arrested the father who was drunk and had hit the mother in front of the child; the mother has refused to co-operate with the police with regard to any criminal proceedings against the father for assault.

- The parents do not show any insight into their relationship difficulties and have refused to attend any counselling or domestic violence intervention programmes.

The paperwork before the Judge in a case like this is likely to contain, as well as statements from the social workers, parents and child’s guardian, evidence from the police, such as their own notes as to when they were called out and what happened, medical evidence to deal with alcohol misuse, possibly a report from a psychologist or psychiatrist. You can see why it is both helpful and necessary to put the issues in the case into one accessible document as even a simple case can generate a lot of written evidence.

If the parents can accept the threshold

The matter will then proceed to the ‘welfare stage’ i.e. where the Judge has to decide what if any order is right in this case. This will depend whether or not the parents have accepted they have difficulties and are willing to work at them. If so, no order or a supervision order may be appropriate. However, if the parents are found to have caused their child to suffer significant harm and do nothing to show how they will change for the future, or if the parents refuse to agree that there is anything wrong at all with their parenting, the court is likely to think a care order is the right order to make.

This will allow the LA to also have parental responsibility for the child and will put them in the driving seat with regard to making decisions to safeguard the child’s future – which could include removing him to an adoptive or foster placement.

If the parents don’t accept the threshold

Then the Judge will need to read all the written evidence and hear oral evidence from everyone involved and then make a decision about what did or didn’t happen. Sometimes there has to be a separate court hearing to make a decision about an interim care order before the final hearing, but it is possible to wait until the final hearing to make a decision about threshold.

It is vital if parents don’t agree with the threshold criteria that they given their solicitors full information as soon as possible and produce their own written document in response.

What Judges have said about meeting threshold

The most significant case concerning threshold criteria is that of re B in the Supreme Court in 2013 which confirmed that a decision as to whether the threshold conditions for a care order have been satisfied depends on an evaluation of the facts of the case as found by the judge; it is not an exercise of discretion.

Lady Hale set out in paragraph 193 of her judgment in that case things that the courts should keep in mind when a threshold is in dispute:

- The court’s task is not to improve on nature or even to secure that every child has a happy and fulfilled life, but to be satisfied that the statutory threshold has been crossed.

- When deciding whether the threshold is crossed the court should identify, as precisely as possible, the nature of the harm which the child is suffering or is likely to suffer. This is particularly important where the child has not yet suffered any, or any significant, harm and where the harm which is feared is the impairment of intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development.

- Significant harm is harm which is “considerable, noteworthy or important”. The court should identify why and in what respects the harm is significant. Again, this may be particularly important where the harm in question is the impairment of intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development which has not yet happened.

- The harm has to be attributable to a lack, or likely lack, of reasonable parental care, not simply to the characters and personalities of both the child and her parents. So once again, the court should identify the respects in which parental care is falling, or is likely to fall, short of what it would be reasonable to expect.

- Finally, where harm has not yet been suffered, the court must consider the degree of likelihood that it will be suffered in the future. This will entail considering the degree of likelihood that the parents’ future behaviour will amount to a lack of reasonable parental care. It will also entail considering the relationship between the significance of the harmed feared and the likelihood that it will occur. Simply to state that there is a “risk” is not enough. The court has to be satisfied, by relevant and sufficient evidence, that the harm is likely: see In re J [2013] 2 WLR 649.

Criticisms of the current approach to threshold – are too many cases going to court?

Isabelle Trowler. In her Bridget Lindley Memorial Lecture in March 2019 Care Proceedings in England: The Case for Clear Blue Water, raised a variety of concerns about what is beyond the recent and serious increase in number of cases coming to court.

She has seen the concept of ‘significant harm’ change and parents who would have once been described as ‘struggling in difficult circumstances’ are now accused of ‘neglect’. She found a lower – but inconsistent – tolerance for diverse standards of parenting with social workers becoming increasingly ‘pro child’, together with fears that the ‘march of predicative harm’ and the mis-use of section 20 has damaged relationships with parents and thus harmed the guiding force of the Children Act – that parents and professionals should work in partnership.

Isabelle Trowler was concerned to note the proportion of children who ended up staying with their parents or within the wider family at the end of contested hearings – about a third. Although in the majority of cases intervention was necessary, if a child ended up with a Supervision Order – was it really necessary for that have gone to court?

But we found a very significant proportion of families subject to proceedings who ended up staying together – with 34 percent of all disposals resulting in a Supervision Order. The public purse pays a heavy price for taking families into court only for children to remain at home anyway; but families and their children pay the heaviest price of all. Inevitably, we had to question – was it really worth it?

The rise in the numbers of applications for care orders may be explained by the

…much greater and deliberate national focus on the early protection of the child, a stronger focus on lower level parenting concerns as first signs of cumulative neglect and with a recognised risk of future harm, a greater sense of urgency to act and secure permanency without delay and the need to act on the side of safety

She poses the worrying question – are we simply asking too much of parents now?

And it did raise an even more troubling question for me – are we asking the impossible of parents? We have an incredibly strong child focus and that is laudable – and that is something that we do not want to change – but in doing so have we made, inadvertently, the family the enemy? We have a multitude of professionals looking out for the rights of a child we have the local authority social worker and their supervisor and their manager, and then there is the foster carer, for example, and their supervising social worker and of course their manager. There is the independent reviewing officer and of course their manager. Then once we hit the court arena, we have the children’s guardian and then their supervisor and the entire hierarchy of Cafcass. That is a lot of people looking out for the child. Maybe as it should be. But is it fair? We are asking parents, often powerless anyway, often frightened and furious, to stand up to everyone else. This feels uncomfortable.

There is a need for some ‘clear blue water’ between those families who could continue to care for their children with help and support and those children who do need to be ‘rescued’ from situations that cannot or will not change within the child’s timescales. Lack of tolerance for diverse parenting standards, coupled with lack of resources appears to be creating a situation where the focus is on going to court.

But for the family justice system to work effectively and fairly, there should be clear blue water between those children who are brought into public care proceedings and other local children who have suffered significant harm or who are at risk of being so. But for there to be clear blue water between these two groups of families, this requires the local authority to be sufficiently equipped to support families and to manage the risk to children within their communities. This requires the right resource spent on the right things and a social work profession with the necessary knowledge and skill to practise confidently at all levels.

Further reading

- Here is an interesting case which decided to what extent harm suffered by other children from a previous relationship could be relied upon to provide the threshold criteria for proceedings now.

- Here is another case where the Judge considered threshold carefully and concluded that it was satisfied.

- In this case the Judge decided that threshold was NOT met as the child’s injuries could have been caused by Vitamin D deficiency.

- In this case, the judge was highly critical of the LA’s evidence, decided that threshold was not met and returned the child to his mother.

- In this case, the President of the Family Division was appalled by the lack of any analysis by the LA of their case against a father; he found threshold was not met.

- Neglect in the context of the criminal law – independent analysis and proposals for reform 2013