In the light of concerns about the Ben Butler case in June 2016, this post by Sarah Phillimore attempts to explain the law that will apply in the family courts when a child has been hurt and there are a number of adults who could have done it – the so called ‘pool of perpetrators’.

If you want to know more about the practicalities of the court process from a parent’s perspective, please see this guest post by Suesspiciousminds ‘The Social Worker tells me my child has been hurt’.

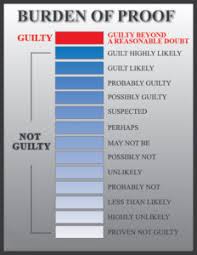

There is often confusion expressed about why both criminal AND family cases can run together, based on the same concerns that a child has been hurt. In some cases, the criminal proceedings will stop or not even start and only the family case continues. This is because of the different roles and responsibilities of the criminal and family courts. Criminal courts, in essence, exist to identify criminals and punish them. As punishment can involve a deprivation of liberty by sending someone to prison, the standard of proof is high – ‘beyond reasonable doubt’.

Family cases however are about protecting children so the focus is different and the standard of proof is lower. There are many parents however who argue that it is simply wrong to make findings about children being injured and remove them from their families on the basis of that lower standard of proof. However, it will probably take an Act of Parliament to change this as Judges are now very clearly bound by decisions of the Supreme Court.

The relevant law – general principles about establishing facts

The court should consider the following issues when it needs to make a finding about what happened in any particular case:

- Articles 6 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights [ECHR] which means the court must respect the right to family life and the right to a fair trial.

- A finding of fact by a Judge that someone hurt a child is a serious thing; therefore anyone at risk of such a finding being made against them must have a chance to be part of the court proceedings and be able to make their case. If someone is a vulnerable adult and needs help from, for e.g. an intermediary, this should be considered by everyone at an early stage

- The ‘burden of proof’ lies on the person who makes the allegation, in this case the local authority. This means that it is not the adult’s responsibility to prove they did not hurt the child; the local authority must prove they did.

Burden and standard of proof in ‘binary’ system

- The standard of proof is the ‘balance of probabilities’ – it must be more than 50% likely that something happened: see Re B (Care Proceedings: Standard of proof) [2008] UKHL 35. In the words of Baroness Hale at paragraph 70: “I…would announce loud and clear that that the standard of proof in finding the facts necessary to establish the threshold at s31 (2) or the welfare considerations at s1 of the 1989 Act is the simple balance of probabilities, neither more not less. Neither the seriousness of the allegations nor the seriousness of the consequences should make any difference to the standard of proof to be applied in determining the facts. The inherent probabilities are simply something to be taken into account, where relevant, in deciding where the truth lies”.

- If a fact is to be proved the law operates a ‘binary system’ which means it is either true or it is not.

- Findings of fact must be based on evidence not speculation. As Munby LJ (as he then was) observed in Re A (Fact Finding: Disputed findings) [2011] 1 FLR 1817 “it is an elementary position that findings of fact must be based on evidence, including inferences that can be properly drawn from evidence and not suspicion or speculation”.

- The court’s task is to make findings based on an overall assessment of all the available evidence. In the words of Butler-Sloss P in Re T [2004] 2 FLR 838: “Evidence cannot be evaluated and assessed separately in separate compartments. A judge in these difficult cases must have regard to the relevance of each piece of evidence to other evidence and to exercise an overview of the totality of the evidence in order to come to the conclusion whether the case put forward by the local authority has been made out to the appropriate standard of proof”.

- If it is suggested that something is ‘very unlikely’ to have happened, that does not have an impact on the standard of proof. See BR (Proof of Facts) [2015] EWFC 41 (11 May 2015) where Jackson J commented at paras 3 and 4:

The court takes account of any inherent probability or improbability of an event having occurred as part of a natural process of reasoning. But the fact that an event is a very common one does not lower the standard of probability to which it must be proved. Nor does the fact that an event is very uncommon raise the standard of proof that must be satisfied before it can be said to have occurred.

Similarly, the frequency or infrequency with which an event generally occurs cannot divert attention from the question of whether it actually occurred. As Mr Rowley QC and Ms Bannon felicitously observed:

“Improbable events occur all the time. Probability itself is a weak prognosticator of occurrence in any given case. Unlikely, even highly unlikely things, do happen. Somebody wins the lottery most weeks; children are struck by lightning. The individual probability of any given person enjoying or suffering either fate is extremely low.”

I agree. It is exceptionally unusual for a baby to sustain so many fractures, but this baby did. The inherent improbability of a devoted parent inflicting such widespread, serious injuries is high, but then so is the inherent improbability of this being the first example of an as yet undiscovered medical condition. Clearly, in this and every case, the answer is not to be found in the inherent probabilities but in the evidence, and it is when analysing the evidence that the court takes account of the probabilities.

What happens if a witness lies about something?

- An important part of the assessment is what the court thinks about the reliability of the adult’s evidence. The court will be worried if someone is found to have lied about something, but that does not necessarily mean that person has lied about everything. The court will keep in mind the warning in R v Lucas [1981] QB 720 that “if a court concludes that a witness has lied about a matter, it does not follow that he has lied about everything. A witness may lie for many reasons, for example out of shame, humiliation, misplaced loyalty, panic, fear, distress, confusion and emotional pressure”.

Expert witnesses

- With regard to evidence provided by expert witnesses, the court should consider the following:

- First, whilst it may be appropriate to attach great weight to clear and persuasive expert evidence it is important to remember that the roles of the court and expert are distinct and that it is the court that is in the position to weigh the expert evidence against the other evidence: see, for example, Baker J in Re J-S (A Minor) [2012] EWHC 1370.

- Secondly, the court should always remember that today’s medical certainty may be disregarded by the next generation of experts. As Hedley J observed in Re R (Care Proceedings Causation) [2011] EWHC 1715 “there has to be factored into every case…a consideration as to whether the cause is unknown”.

Particular considerations in a case when a child has suffered injury

The court will consider the decision of the Supreme Court in in Re S-B (children) (non-accidental injury) [2009] UKSC 17.

Was the injury an accident?

- If the court is satisfied that the child sustained injuries, the first question is whether they were caused ‘non accidentally’.

- The court is reminded of the comments of Ryder LJ about the expression “non-accidental injury” in S (A Child) [2014] EWCA Civ 25:-I make no criticism of its use but it is a ‘catch-all’ for everything that is not an accident. It is also a tautology: the true distinction is between an accident which is unexpected and unintentional and an injury which involves an element of wrong. That element of wrong may involve a lack of care and/or an intent of a greater or lesser degree that may amount to negligence, recklessness or deliberate infliction. While an analysis of that kind may be helpful to distinguish deliberate infliction from say negligence, it is unnecessary in any consideration of whether the threshold criteria are satisfied because what the statute requires is something different namely, findings of fact that at least satisfy the significant harm, attributability and objective standard of care elements of section 31(2).

- For an example of an injury deemed accidental, see EF (a child), Re [2016] EWFC B107 (15 September 2016) the court accepted the parents’ account and thus the LA had not made out its case.

If it wasn’t an accident – who did it?

- Having established the injury was not an accident, attention turns to whether or not the court can say who caused the injury. The ‘threshold criteria’ (what the court needs to find proved in order to make a care order) can be established by findings that a child has suffered harm whilst in the care of his parents, or other carers, without the need to establish precisely who caused the injuries. Nevertheless, where possible, it is clearly a good idea to identify who has caused the injuries:

- to be as clear as possible about future risks to the child and how to deal with those risks.

- The child has a right to know what happened to him, if it is possible to find out.

How hard should the court try to find out who did it?

- However, the court should not ‘strain unnecessarily’ to identify who hurt the child. If the evidence does not support a specific finding against an individual(s) the court should attempt to identify the ‘pool’ of possible perpetrators. See Lancashire CC v B [2000] 2 AC 147 and North Yorkshire CC v SA [2003] 2 FLR 849.

- The identification of a pool of possible perpetrators is sometimes necessary in order to determine if the child’s parents or carers are to blame for the harm suffered by the child. If the child was hurt by someone outside the home or family – for example by someone at school or at hospital – then it would usually be unfair to say that this is the parent’s/carer’s fault.

- In considering whether a particular individual should be within the pool of possible perpetrators the test is whether there is a real possibility that he or she was involved.

- If the court identifies a pool of possible perpetrators the court should be wary about expressing any view as to the percentage likelihood of each or any of those persons being the actual perpetrator. (In the words of Thorpe LJ: “Better to leave it thus”).

What happens in the future if a parent is found to be in the ‘pool of perpetrators?’

As a parent, this could have a serious impact on your current or future family life. You may find that you need to submit to a risk assessment from the local authority if you want to care for your children.

However, if you become involved in care proceedings in the future, the court is clear that a previous finding that you were ‘in the pool’ can NOT be treated as simply ‘proof’ that you hurt a child and it cannot be used in this way as part of any threshold document to assert that your current children are at risk.

However, the fact that a parent was part of a household where a child suffered injury, cannot just be ignored and will need to form part of a careful assessment of current circumstances.

See In the matter of J (Children) [2013] SC 9 – the judgment of Lady Hale at para 52:

52. It is, of course, a fact that a previous child has been injured or even killed while in the same household as this parent. No-one has ever suggested that that fact should be ignored. Such a fact normally comes associated with innumerable other facts which may be relevant to the prediction of future harm to another child. How many injuries were there? When and how were they caused? On how many occasions were they inflicted? How obvious will they have been? Was the child in pain or unable to use his limbs? Would any ordinary parent have noticed this? Was there a delay in seeking medical attention? Was there concealment from or active deception of the authorities? What do those facts tell us about the child care capacities of the parent with whom we are concerned?

53. Then, of course, those facts must be set alongside other facts. What were the household circumstances at the time? Did drink and/or drugs feature? Was there violence between the adults? How have things changed since? Has this parent left the old relationship? Has she entered a new one? Is it different? What does this combination of facts tell us about the likelihood of harm to any of the individual children with whom the court is now concerned? Does what happened several years ago to a tiny baby in very different circumstances enable us to predict the likelihood of significant harm to much older children in a completely new household?

54. Hence I agree entirely with McFarlane LJ when he said that In re S-B is not authority for the proposition that “if you cannot identify the past perpetrator, you cannot establish future likelihood” (para 111). There may, or may not, be a multitude of established facts from which such a likelihood can be established. There is no substitute for a careful, individualised assessment of where those facts take one. But In re S-B is authority for the proposition that a real possibility that this parent has harmed a child in the past is not, by itself, sufficient to establish the likelihood that she will cause harm to another child in the future.

It is very important to investigate all the surrounding circumstances thoroughly and not to risk reversing the burden of proof. The Court of Appeal commented in B (Children : Uncertain Perpetrator) (Rev 1) [2019] EWCA Civ 575 (04 April 2019) that it might be better to talk more about a ‘list’ than a ‘pool’.

Further reading

Barristers at 6 Pump Court consider recent developments in the law relating to injuries to very young children, 22 March 2017.

We believe you harmed your child: the war over shaken baby convictions The Guardian 8 Dec 2017