Resources

The information set out here, is a summary from the three documents below.

The President’s Guidance from 2014 The International Child Abduction and Contact Unit (ICACU) (judiciary.uk)

The ICACU’s guidance on completing the request form icacu_request-for-co-operation-guide.docx (live.com)

Protecting Children and Families Across Boarders [CFAB] Kinship assessment guidance CFAB | International Kinship Care Guide. This guidance deals with

- The steps which should be taken whilst identifying, assessing and preparing potential carers overseas for an international kinship care placement when the child is in local authority care.

- The complexities in ensuring that orders are mirrored and/or recognised in the receiving country.

- Recommendations for the ongoing relationship between the relevant authorities in each country to ensure that responsibilities are clear and are mutually agreed.

- Barriers to permanency which would need to be considered before placement, or which would need additional support for the child and carer to ensure that the child has a successful and permanent placement.

Care proceedings with an international element – how do you get information about family members? How do you assess them?

- An increasing number of cases have an international element. This brings with it almost inevitably great potential for delay and costs, in making inquiries and getting documents translated. It’s imperative that we do not add to these problems so we need to be alert when a case is likely to require consideration of the practices and procedures of another country, so we do not cause additional delay and we make sure that assessments or placement plans will be recognised by a foreign country.

- As the introduction to the CFAB Kinship Care assessment guide sets out:

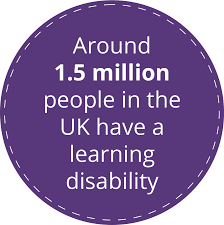

Both the Children Act 1989 and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child place an emphasis on children remaining with family. The practicalities of supporting this across international borders are delicate and complex, requiring specialist guidance to ensure they are carried out properly and with the best interests of the child at the forefront. There is otherwise the risk of vulnerable children being placed with inappropriate carers, of children being returned to the originating local authority due to faulty legal procedures and of family breakdown because the right support measures were not proactively identified….Despite the risks, the scale of the problem for these vulnerable children is unknown. The charity Children and Families Across Borders (CFAB) estimates that there are 18,000 Looked After Children in England and Wales who may have family members abroad that could – and should – be explored as options for their long term care.

What is the 1996 Hague Convention?

- The HCCH (Hague Conference on Private International Law Conférence de La Haye de droit international privé) is an intergovernmental organisation which aims to secure the “the progressive unification of the rules of private international law”

- The HCCH’s mission is …[to provide] internationally agreed solutions, developed through the negotiation, adoption, and operation of international treaties, the HCCH Conventions, to which States may become Contracting Parties, and soft law instruments, which may guide States in developing their own legislative solutions.

- Since the inception of the HCCH, it has created over 40 Conventions and instruments. One of its ‘core’ Conventions is The 1996 Hague Convention on Jurisdiction, Applicable Law, Recognition, Enforcement and Co-operation in Respect of Parental Responsibility and Measures for the Protection of Children [the 1996 Hague Convention]. HCCH | About HCCH

- The Hague Conference website[1] has helpful information and documents about each Hague Convention and explains which countries are party to that Convention and whether the Convention is in force between the UK and another country.

- As of October 2022 the 1996 Hague Convention has 54 contracting states. HCCH | #34 – Status table and a broad scope. It aims to avoid conflicts between legal systems in respect of jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition and enforcement of measures for the protection of children and emphasises the importance of international co-operation. It provides the basic framework for exchange of information and collaboration by setting up ‘Central Authorities’ in each contracting state.

- Article 3 sets out the issues within its scope HCCH | #34 – Full text which includes guardianship and analogous institutions, the placement of a child in a foster family or institutional care, and the supervision by a public authority of the care of a child – therefore if you want to carry out an assessment of a family member in a Hague Convention State you will be within scope.

- If you want information from a country outside the 1996 Hague Convention then I am afraid we seem to be limited to the Working with foreign authorities: Child Protection cases and care orders. Advice template (publishing.service.gov.uk) This is not very informative and essentially tells you to contact the Embassy or CFAB.

What is the ICACU?

- The ICACU is the operational Central Authority for England for the 1996 Hague Convention. It’s a small administrative unit and its staff are not lawyers or social workers. It is set up to make requests for co-operation to another country, for the collection and exchange of information if the other country is a State Party to the 1996 Hague Convention; and the request for co-operation is within scope of the Convention.

- The ICACU is also the operational Central Authority for the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction and the 1980 Hague European Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Decisions Concerning Custody of Children and Restoration of Custody of Children.

- The ICACU does not become directly involved in the court proceedings. Central authorities are not under any obligation to engage in proceedings and do not require a court order before discharging their duties and responsibilities under 1996 Hague Convention

- If you want to place a child in another country, this is a matter for the requested country – a placement which we may think is a private law placement, may be regarded as a public law placement by the requested country.

- A request for co-operation can be made to establish if, in principle, the consent of the other country would be required for placement even if the care plan for the child is not yet fully informed.

- For requests for co-operation under the 1996 Hague Convention to or from Wales, you should contact the Welsh Government. Scotland and Northern Ireland have their own Central Authorities.

What is within the scope of the ICACU?

- You need information from the other country to help you formulate a care plan, for example:

- identifying and/or assessing potential kinship carers

- Confirmation if you need the other country’s consent to place children there

- the other country’s procedure for progressing a request to transfer jurisdiction under Articles 8 and 9 of the 1996 Hague Convention, because its considered that another country is best placed to make decisions about the child’s future.

What is outside the scope of the ICACU?

17. Article 4 of the 1996 Hague Convention explains what is not in scope of the Convention. This includes adoption, measures preparatory to adoption, or the annulment or revocation of adoption.

- If your request is not in scope of the 1996 Hague Convention, it may be in scope of another European Regulation or international Convention and another central authority or body may be able to assist.

- With regard to serving documents abroad, or taking evidence abroad, the Senior Master is the central authority under Article 3 of the 1965 Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters (‘the 1965 Hague Convention’) and Article 2 of the 1970 Hague Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters (‘the 1970 Hague Convention’). If dealing with these matters you need to contact the Foreign Process Section based in the Royal Courts of Justice. [[email protected]].

- A request for copies of foreign court papers is more likely to be in scope of the 1970 Hague Convention.

- If you wish to get information on someone’s criminal record outside the jurisdiction, contact the UK Central Authority for the Exchange of Criminal Records International Criminal Conviction Exchange Department ACRO Criminal Records [email protected]

- If you need to let a foreign jurisdiction know that one of its citizens is involved in care proceedings, following Re E (Brussels II Revised: Vienna Convention: Reporting Restrictions) [2014] EWHC 6 (Fam), [2014] 2 FLR 151, you must contact the relevant consular authorities. This applies also to inquiries about passports or other travel documents. A ‘Consular authority’ refers to an official appointed by a sovereign state to protect its commercial interests and help its citizens . It can refer to a High Commission, Embassy or Consulate.

- A request for an opinion on how a foreign country might recognise an order of the English court is not a question for central authorities. You will need to think about getting permission for expert advice on the law in the relevant jurisdiction.

- If you want someone to give oral evidence in the English court while they are physically present in a foreign state, for e.g. via video link or phone, you have to get permission from the foreign state. This is done via the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office [FCDO] “Taking of Evidence Unit” [“ToE”]. HMCTS will contact the ToE on behalf of any party who notifies the tribunal that they want to rely on oral evidence from a person abroad, so all that that party needs to do is notify the tribunal of: a. the name of that person and case number; b. the country the person would be giving evidence from; c. if it is not the appellant what the evidence would be about; d. the date of any listed hearing This must be done as soon as it is known that a person wishes to give evidence from abroad, to avoid the risk of delaying any hearing.

How do I contact the ICAU?

- The ICACU’s general office telephone number is 0203 681 2608 and can be used by parties seeking “in principle” advice based on the ICACU’s experience of the other country but email contact is much preferred: [email protected].

- In public law children cases the ICACU prefers that the local authority contact the ICACU about a request for co-operation It is administratively more efficient and less likely to give rise to miscommunication if the ICACU is in contact with one party only.

Making a request for co-operation and timescales

- The form is on line – see above. If as a social worker you are not sure if your request falls under the 1996 Hague Convention, you must get advice from your legal department as the ICACU does not give legal advice. The form requires you to identity the relevant Articles of the Hague Convention that inform your request.

- But you can make a preliminary inquiry to the ICACU prior to a formal request if your legal team aren’t sure. Identify in the subject line of the email that this is a ‘general inquiry’ and set out your identity and country you are asking about. Make it clear if your request is urgent.

- The ICACU does not open a case file in response to a general enquiry; it only does so when it receives a formal request for co-operation.

- Article 37 of the 1996 Hague Convention says that the ICACU shall not request or transmit any information if to do so would be likely to place the child’s person or property in danger or constitute a serious threat to the liberty or life of a member of the child’s family. You will be asked to confirm that the request does not engage Article 37.

- The ICACU cannot compel the requested central authority or foreign competent authorities to respond within a specific timetable and different countries have differing views as to what information or assistance can be provided. It is therefore difficult to predict how long it will take for you to get any useful information. Therefore, it is really important to do all you can at your end to keep things moving. You need to make a relevant and focused request as early as possible in the proceedings.

- Do not simply send the court bundle – that is likely to slow things down. The following information is key:

- The court timetable and when hearings are listed – and remember when fixing the timetable in the English court, to build in realistic timescales for a reply from the ICACU

- The ICACU does not require a court order to act but if the court has ordered the local authority to make a request, include a copy of the sealed order – but remember that orders should not be made against foreign authorities.

- A clear background case summary, agreed by all parties if possible. If it is not agreed, make this clear.

- The full names and dates of birth of the children and relevant adults with explanation of family relationships – if complex, a genogram can help

- Explain ‘technical language’. What do you mean by ‘section 20’? What do you mean by ‘kinship care’?

- Avoid acronyms – the other country is unlikely to understand what is meant by ‘IRH’ for e.g.

- If you are trying to identify potential kinship carers, provide as much information as possible to assist the other country to trace the individuals concerned; if current contact details are not known, provide as much information as possible about last known addresses etc.

- Explain what you would find helpful for a kinship assessment to cover – but you cannot require the foreign authorities to carry out an assessment in a particular way.

- A rough timeline of an approach to the ICACU can look like this. You can see how each step of the process carries with it potential for delay.

- The local authority decides to make a request for co-operation

- The ICACU receives the request

- The ICACU requests translation of necessary documents

- The request is sent by the ICACU to the other country

- The other country makes inquiries.

- Arrangements are made to translate documents

- The ICACU responds to the local authority or makes requests for further information

- the ICACU sends the response to the local authority

- Translation can be a big problem – the ICACU has a limited budget. It will translate the initial request but you will have to decide at your end who is preparing and paying for translation of any supporting documents. If you are able to arrange for translation of your initial request, that can help speed things up.

Central Authority contact details

Scotland and Northern Ireland have different legal systems from England and Wales and the law in Scotland and Northern Ireland also differs in some respects. England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland each have their own Central Authority for the Regulation. Wales has its own Central Authority for the 1996 Hague Convention.

| Central Authority for England (for the 1996 Hague Convention) The International Child Abduction and Contact Unit The Official Solicitor & Public Trustee Office Post Point 0.53 102 Petty France London SW1H 9AJ DX: Post Point 0.53 Official Solicitor & Public Trustee DX 152384 Westminster 8 tel: +44 (0)20 3681 2756 www.gov.uk e-mail for new requests and general enquiries only: [email protected] | The International Child Abduction and Contact Unit (ICACU) is open Monday to Friday. In an emergency outside these hours you should contact the Reunite International Child Abduction Centre on tel 0116 2556 234. Please note that the office of the ICACU is not open to the public. Emails received after 2.00pm will not be considered until the next working day except in cases of extreme urgency (please indicate in the subject heading whether flight risk / abduction in transit / imminent risk of harm) |

| Central Authority for Northern Ireland Central Business Unit Northern Ireland Courts & Tribunals Service 3rd Floor Laganside House 23-27 Oxford Street BELFAST BT1 3LA Northern Ireland United Kingdom tel: +44 (0)28 9072 8808 fax: +44 (0)28 9072 8945 Internet: http://www.courtsni.gov.uk/ email: [email protected] is used for applications under 1980 & 1996 Hague conventions along with Brussels II requests | |

| Central Authority for Scotland Scottish Government Central Authority and International Law Branch GW15 St. Andrew’s House EDINBURGH EH1 3DG Scotland United Kingdom tel: +44 (0)131 244 4827 fax: +44 (0)131 244 4848 e-mail: [email protected] | |

| Central Authority for Wales Welsh Government Social Services and Integration Cathays Park CARDIFF CF10 3NQ United Kingdom tel.: +44 (29) 2082 1518 fax: +44 (29) 2082 3142 email: [email protected] | The Welsh Government is the Central Authority for Wales for the 1996 Hague Convention only. |

Other useful resources

| The Foreign Process Section Room E16 Royal Courts of Justice Strand London WC2A 2LL United Kingdom tel.: +44 (0)20 7947 6691 +44 (0)20 7947 7786 +44 (0)20 7947 6488 +44 (0)20 7947 6327 +44 (0)20 7947 1741 fax: +44 870 324 0025 email: [email protected] | The Senior Master is the transmitting agency under Article 3 of the 1965 Hague Convention and the central authority under Article 2 of the 1970 Hague Convention. The Foreign Process Section is the administrative unit which supports the Senior Master. |

| The Hague Conference on Private International Law Permanent Bureau Hague Conference on Private International Law Churchillplein 6b 2517 JW THE HAGUE The Netherlands Fax: +31 (0)70 360 4867 www.hcch.net | The Hague Conference does not provide legal advice but their website has copies of all the Conventions, Explanatory Reports, a status table for each Convention and other useful documents. |

[1]https://www.hcch.net: At Homepage scroll down to Sitemap, at Sitemap use the dropdown menu for ‘Instruments’ and go to ‘Conventions, Protocols and Principles’ for an interactive list of all the Conventions.