- Your starting point in care proceedings is section 31 of the Children Act 1989. You can find the whole Act here or read what Wikipedia says about it.

- For more detail about this issue from the social worker’s perspective, please see this helpful article.

- For NSPCC Guidance on how to notice signs of abuse, see this document from December 2017

Section 31 of the Children Act allows a Local Authority (LA) ‘or authorised person’ to apply to the court for an order which makes it lawful to to put a child in the care of a LA, or under the supervision of a LA. At the moment, the only other ‘authorised person’ is the NSPCC.

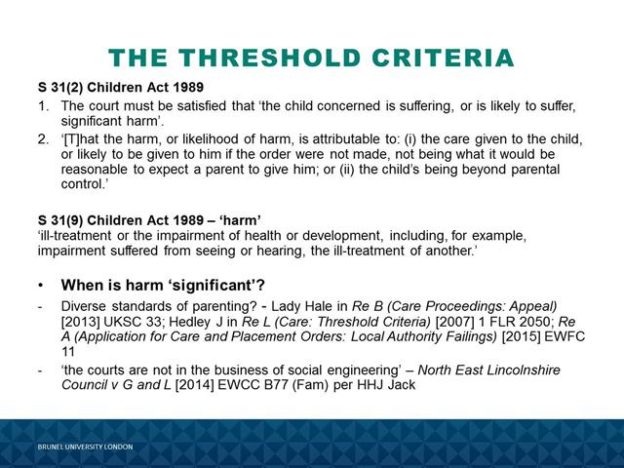

It is NOT the social worker who decides whether or not there should be a care or supervision order. This is a decision for the Judge or the magistrates. They are only allowed to make a care or supervision order if :

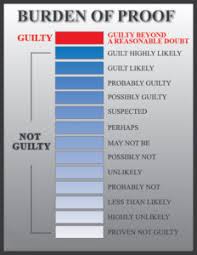

- they are satisfied there is evidence (‘threshold criteria’)

- which proves on the balance of probabilities, that:

- the child is suffering OR;

- is likely to suffer significant harm in the future AND;

- this significant harm will be a result of either ‘bad’ parenting – likely to be seen as the parents’ fault; OR

- the child is beyond parental control – which may not necessarily be seen as the parents’ fault.

[For discussion about what is meant by ‘beyond parental control’ see the case of P (permission to withdraw care proceedings) [2016] EWFC B2.]

The ‘significant harm’ has got to relate to what the parents are doing or likely to do when they are caring for their child. The court will consider the standards of a ‘reasonable parent’: see Re A (A Child) [2015] EWFC 11 and Re J (A Child) [2015] EWCA Civ 222.

In one case, LCC V AB and Others [2018] the LA and Guardian wanted to argue that the threshold regarding significant harm was crossed when a terminally ill mother wanted her children to go into foster care before she died; the court found that it was not and refused to make a care order. The Judge commented at para 26:

Recognising the difficulties she was going to face in her medical treatment and in her medical condition, she made, in my judgement, a timely request for alternate care. In so doing, in my judgement, she acted as a perfectly reasonable, loving, caring mother and requested that the children be cared for by the local authority. She has not subsequently wavered in her acceptance and understanding that the children should remain in full-time foster care, however much no doubt she would want to be looking after them herself. She has cooperated at every stage with the local authority. She has been a willing recipient of advice and support, as is exemplified, as I set out earlier in this judgment, with her acceptance of the advice about the frequency of overnight and weekend contact.

The court will look at two different issues:

- how is the parent looking after the child? Is the kind of care they are giving the kind you would expect from a ‘reasonable parent’? or

- Is the child out of control? for example, not going to school or running away from the parents and getting into trouble?

There is already quite a lot to unpick here.

- What does ‘harm’ mean?

- What does ‘significant’ mean?

- What happens when the court is worried about risk of future harm?

What do we mean by ‘harm’ ?

Section 31(9) of the Children Act tells us that harm means:

- ‘ill-treatment or the impairment of health or development including, for example, impairment suffered from seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another’.

This last part about being exposed to someone else being badly treated, was added by the Adoption and Children Act of 2002. It is intended to cover such circumstances as a child who witnesses or hears someone else being hurt, for example if the parents are fighting or shouting at one another at home.

Development means ‘physical, intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development’

Health means ‘physical or mental health’

Ill-treatment‘ includes sexual abuse and other forms of bad treatment which are not physical. This includes ’emotional harm’. This is the category of harm which probably cases most concern for a lot of people; they are concerned about what kinds of behaviour get put into this category. We will look at the issue of ’emotional harm’ more closely in another post.

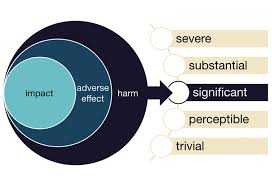

What do we mean by ‘significant’ ?

Section 31(9) tells us what is meant by ‘harm’. But it doesn’t give a definition of what is meant by ‘significant’. The original guidance to the Children Act 1989, issued by the Department of Health, stated that:

Minor shortcomings in health care or minor deficits in physical, psychological or social development should not require compulsory intervention unless cumulatively they are having or are likely to have, serious and lasting effects on the child.

We can get further guidance from looking at Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights [ECHR]. Article 8 exists to protect our rights to a family and a private life. Article 8 makes it clear that the State can only interfere in family life when to do so is lawful, necessary and proportionate.

Proportionality is a key concept in family law. A one off incident – unless extremely serious, such as a physical attack or sexual assault – is unlikely to justify the making of a care order as the court would be unlikely to agree that a single incident would have long lasting and serious impact on a child. But the same type of incident, repeated over time may well have very serious consequences for the child.

Read Article 8 here. For further discussion about what is meant by proportionality, see our post here.

There are some useful law reports where ‘significant harm’ has been discussed. For example, Baroness Hale stated in B (Children) [2008] UKHL 35:

20. Taking a child away from her family is a momentous step, not only for her, but for her whole family, and for the local authority which does so. In a totalitarian society, uniformity and conformity are valued. Hence the totalitarian state tries to separate the child from her family and mould her to its own design. Families in all their subversive variety are the breeding ground of diversity and individuality. In a free and democratic society we value diversity and individuality. Hence the family is given special protection in all the modern human rights instruments including the European Convention on Human Rights (art 8), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (art 23) and throughout the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. As Justice McReynolds famously said in Pierce v Society of Sisters 268 US 510 (1925), at 535, “The child is not the mere creature of the State”.

21. That is why the Review of Child Care Law (Department of Health and Social Security, 1985)) and the white paper, The Law on Child Care and Family Services (Cm 62, 1987), which led up to the Children Act 1989, rejected the suggestion that a child could be taken from her family whenever it would be better for her than not doing so. As the Review put it, “Only where their children are put at unacceptable risk should it be possible compulsorily to intervene. Once such a risk of harm has been shown, however, [the child’s] interests must clearly predominate” (para 2.13).

In 2013 the now Lady Hale stated in Re B (A child) 2013 UKSC 33

Significant harm is harm which is “considerable, noteworthy or important”. The court should identify why and in what respects the harm is significant. Again, this may be particularly important where the harm in question is the impairment of intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development which has not yet happened.

The harm has to be attributable to a lack, or likely lack, of reasonable parental care, not simply to the characters and personalities of both the child and her parents. So once again, the court should identify the respects in which parental care is falling, or is likely to fall, short of what it would be reasonable to expect.

Sometimes, a lot of time is needed in care cases to argue about whether or not the harm in a particular case is serious enough to meet this statutory requirement. If the Judge decides there is no significant harm either being suffered now or likely to be suffered in the future, then he or she cannot make a care order or supervision order.

If he or she decides that there is enough evidence of significant harm, we move to the second stage of the necessary legal test – whether or not to make a care or supervision order is in the child’s best interests. This is called the ‘welfare stage’ of the test and we will examine this in another post.

Different types of abuse which can cause significant harm

In some cases it is very easy to see that a child has already suffered significant harm, for example when a child has been sexually abused or physically attacked. The court is likely to have clear and first hand evidence in the form of reports from doctors or the police who have examined or interviewed the child. The majority of people agree that being attacked or sexually abused is likely to be very harmful to children.

The more difficult cases involve issues of neglect and emotional abuse where it is hard to find one particular incident that makes people worried – rather it is the long term impact on the child of the same kind of harm continuing. These cases are particularly difficult when it is also clear that there are positives for the child in his or her family and the court has to decide whether the positive elements of family life are outweighed by the bad, or whether the family can make necessary changes quickly enough to meet the needs of the child.

For example, if on occasion you get angry with your child and shout at him or smack him it is highly unlikely your child would be considered at risk of significant harm if for the majority of the time you are loving and patient. But imagine a child who is shouted at and hit on a daily basis. It is not difficult to see how living in such an environment is likely to cause that child significant emotional or even physical harm.

See what the House of Commons Education Committee said about the child protection system in 2012.

Table 1: Children and young people subject to a Child Protection Plan, by category of abuse, years ending 31 March 2011

More recent statistics from the NSPCC show neglect cases rising from 17,930 in 2013 to 24,590 in 2017; emotional abuse from 13,640 to 17,280.

You can see from the figures that the most common cause for concern about children in every year was the issue of neglect – but we can see a significant and consistent rise in number of cases of emotional abuse. The NSPCC confirmed that in 2015:

Neglect is the top reason why people contact the NSPCC Helpline with their concerns about a child’s safety or welfare – and this has been the case since 2006. In 2014–15 there were 17,602 contacts received by the NSPCC Helpline about neglect (3,019 advice calls and 14,583 referrals), an increase on the previous year13.

In 2012, the Education Committee examined the issue of neglect from paragraph 41 in their report and said:

41. Neglect is the most common form of child abuse in England. Yet it can be hard to pin down what is meant by the term. Professor Harriet Ward told us that, based on her research into what was known about neglect and emotional abuse, “we definitely have a problem with what constitutes neglect” and that “we need to know much more about what we actually mean when we say neglect”. Phillip Noyes of the NSPCC agreed that “There is a dilemma with professionals, and indeed the public, about what comprises neglect, what should be done and how we should do it”. He went on to explain his belief that: “at the heart of neglect […] is a lack or loss of empathy between the parent and child”.

42. There are two statutory definitions of neglect: one for criminal and one for civil purposes. Neglect is a criminal offence under the Children and Young Persons Act 1933 where it is defined as failure “to provide adequate food, clothing, medical aid or lodging for [a child], or if, having been unable otherwise to provide such food, clothing, medical aid or lodging, he has failed to take steps to procure it to be provided”. Action for Children has called for a review of this definition, declaring it “not fit for purpose” because of the focus on physical neglect rather than emotional or psychological maltreatment. Action for Children also believe that the definition leaves parents unclear about their responsibilities towards children and seeks only to punish parents after neglect has happened rather than trying to improve parenting.

[….]

The civil definition of neglect which is used in child and family law is set out in the Children Act 1989 as part of the test of ‘significant harm’ to a child. This is expanded upon in the previous Working Together statutory guidance which describes neglect as:

the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical and/or psychological needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of the child’s health or development. Neglect may occur during pregnancy as a result of maternal substance abuse. Once a child is born, neglect may involve a parent or carer failing to provide adequate food, clothing and shelter (including exclusion from home or abandonment); protect a child from physical and emotional harm or danger; ensure adequate supervision (including the use of inadequate care-givers); or ensure access to appropriate medical care or treatment. It may also include neglect of, or unresponsiveness to, a child’s basic emotional needs.

- With regard to violence in the home between adults there is some useful information from the Royal College of Psychiatrists about the impact upon children of domestic violence here.

- Read what we say about emotional abuse here.

- Further information about the impact of neglect from research at Harvard University.

Future risk of harm – what do we mean by ‘likely to suffer’ ?

Simply to state that there is a “risk” is not enough. The court has to be satisfied, by relevant and sufficient evidence, that the harm is likely

The most difficult cases of all are where a child hasn’t yet suffered any kind of harm but the court is very worried about the future risk of harm. It is this category which has caused most concern to those who worry about the child protection system as they feel strongly it is not fair to a parent to punish him or her by removing their child for something they haven’t yet done.

As Dr Claire Fenton-Glyn explained in her recent study on the law relating to child protection/adoption in the UK, presented to the European Parliament in June 2015:

A major problem with the law prior to 1989 was that it required proof of existing harm, based on the balance of probabilities. The local authority could not take a pre- emptive step to protect a child from apprehended harm, causing significant difficulties, in particular with newborn babies. As such, the inclusion in the Children Act of the future element of “is likely to suffer” was an important innovation, introduced to provide a remedy where the harm had not occurred but there were considerable future risks to the child. However, this has also been the cause of some controversy, as the answer as to whether a child will suffer harm in the future is necessarily an indeterminate and probabilistic one.

You can read about what the Supreme Court decided in a case like this in re B in 2013 where the court had to grapple with the issue of the risk to the child of future emotional harm.

Lady Hale said from para 193:

I agree entirely that it is the statute and the statute alone that the courts have to apply, and that judicial explanation or expansion is at best an imperfect guide. I agree also that parents, children and families are so infinitely various that the law must be flexible enough to cater for frailties as yet unimagined even by the most experienced family judge. Nevertheless, where the threshold is in dispute, courts might find it helpful to bear the following in mind:

(1) The court’s task is not to improve on nature or even to secure that every child has a happy and fulfilled life, but to be satisfied that the statutory threshold has been crossed.

(2) When deciding whether the threshold is crossed the court should identify, as precisely as possible, the nature of the harm which the child is suffering or is likely to suffer. This is particularly important where the child has not yet suffered any, or any significant, harm and where the harm which is feared is the impairment of intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development.

(3) Significant harm is harm which is “considerable, noteworthy or important”. The court should identify why and in what respects the harm is significant. Again, this may be particularly important where the harm in question is the impairment of intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development which has not yet happened.

(4) The harm has to be attributable to a lack, or likely lack, of reasonable parental care, not simply to the characters and personalities of both the child and her parents. So once again, the court should identify the respects in which parental care is falling, or is likely to fall, short of what it would be reasonable to expect.

(5) Finally, where harm has not yet been suffered, the court must consider the degree of likelihood that it will be suffered in the future. This will entail considering the degree of likelihood that the parents’ future behaviour will amount to a lack of reasonable parental care. It will also entail considering the relationship between the significance of the harmed feared and the likelihood that it will occur. Simply to state that there is a “risk” is not enough. The court has to be satisfied, by relevant and sufficient evidence, that the harm is likely: see In re J [2013] 2 WLR 649.

Therefore, if the court is worried about things that happened in the past and wants to use those events as a guide to future risk of harm, it must be clear about what has actually happened in the past – you cannot find a risk of significant harm based on just ‘suspicions’ about what might have happened before.

See further the Supreme Court decision of Re S -B [2009].

Baker J commented in 2013:

In English law, the House of Lords has now concluded definitively that in order to determine whether an event has happened it has to be proved by the person making the allegation on the simple balance of probabilities. Where the law establishes a threshold based on likelihood, for example that a child is likely to suffer significant harm as a result of the care he or she would be likely to receive not being what it would be reasonable for a parent to give, the House of Lords has also concluded that such a likelihood, meaning a real possibility, can only be established on the basis of established facts proved on a balance of probabilities.