Sarah Phillimore: I am grateful to FNF for this guest post. While I do not always agree with what this group says or how they frame it, they at least make the effort to explain and evidence their assertions, for which I am grateful. I certainly prefer their approach to the polarising and unevidenced assertions that this discussion appears to encourage from many on ‘both sides’. I remain convinced that the only respectable conclusion the Inquiry can reach is the urgent need for reliable data. Otherwise it seems we will be doomed to spin this wheel for many more years to come.

The Response of Families Need Fathers to the Family Inquiry Panel

Families Need Fathers @FNF_Media www.fnf.org.uk ‘Families need Fathers – because both parents matter’ is a UK charity founded in 1974 to support the welfare interests of children when families separate, with a focus on parents struggling to secure reasonable or indeed any parenting time, in the absence of good reasons. We believe that the best interests of children would be served if there were a rebuttable presumption of shared care. We aspire to a situation where most children enjoy joint care of their separated parents the benefits of which are supported by research where such arrangements are the norm.

Examples of conflict from our front row FNF speak to tens of thousands of parents a year who come to us for help. We also receive feedback from many lawyers, McKenzie Friends and litigants of their experiences. So here is a cross-section of the kinds of scenarios that we see.

- After separation, all was working well. When mother got a new boyfriend, all contact stopped.

- When father got a new girlfriend, mum first insisted that he could not have the children in her presence and stopped contact. When he took her to court, she alleged inappropriate, sexualised behaviour in front of the child.

- When dad lost his job and reduced child maintenance, mum said “no money, no kids”.

- When dad had a job and paid child maintenance, mum said “more money, or no kids”.

- Mum refused to put dad on the birth certificate and threatens no contact, so dad applies for Parental Responsibility.

- Mum beat dad regularly, when be plucked up the courage to tell the police, she alleged sexual abuse.

- She found out he’d had an affair then phoned the police alleging abuse to get him out of the house.

- She slapped him repeatedly in an intense argument. When he pushed her away she phoned the police.

- He said he would leave, but she threatened him with not seeing the children.

- Both parents were aggressive to each other when drinking.

- Both smoked cannabis, but upon separation mum claimed he was the only one who did it in front of the child.

- He was an alcoholic. There was a violent incident where he hit mum many years ago whilst drunk. He’s been dry since then and the main carer of the child, but now she has applied for legal aid on the basis of this incident.

- Separated father reported the mother to social services when a drug dealer moved in with her and the children. She assaulted him when he came to collect the kids, called the police and claimed he’d carried out the assault.

- Mum suffers from a mental health conditions that cause her difficulty in seeing things with clarity. Or, mum has been the victim of a horrendous abuse herself causing her to feel fearful in situations where she would not have otherwise.

All these of incidents could have happened with parents’ roles reversed of course. All form part of the varied situations that family court judges have to deal with. In each, there will be two sides to the story with varying degrees of supporting evidence. It is the role of the judge to (a) decide whether the facts of each of the claims being made are relevant to the safety of the child and (b) weigh-up the evidence and decide which is more credible when evaluating the risks.

The ‘paramountcy principle’ means that their decision has to be based on the best interests of the child taking into account identified risks from each parent. Charlotte Proudman, in her Guest Post of 3rd July 2019 for the Transparency Project makes a range of suggestions as to what is wrong with family justice (and there is much that is). However, her assertions appear to be based, at best on her experience of being a self-proclaimed ‘feminist barrister’ (and hence unlikely to see a typical cross-section of cases) and at worst on dogma.

Claims, for example, that the majority of cases stem from safeguarding concerns relating to family abuse are precisely what it is the judge’s job to decide based on evidence. Both sides are likely to make such assertions. Similarly, claims that Cafcass documenting of allegations of father’s controlling behaviour being discarded are also problematic. If a judge ignores a report in which there are concerns, that would be a basis for appeal. A judge may well dismiss the allegation because the evidence provided by the father was stronger than that offered by the mother, perhaps compelling. It could be that there was evidence of the mother or both parents exercising inappropriate controlling behaviour over the other, the nature of which (a) was unlikely to manifest itself now they don’t live together or (b) is insufficient to warrant placing the child into care.

The current move is to ‘ban abusers from having contact with their children’.

The definition of domestic abuse has been broadened recently. It includes shouting and

aggressive behaviour so the other parent is frightened. Such behaviour is fairly common by both parents who find reason to find fault in each other prior to or in the throes of separation. If that were the ‘abuse’ that has taken place, one would hope that nobody would suggest that neither, or either parent, should be stopped from parenting the child.

However, few studies have gone so far as far as to determine how many of these allegations were found to be irrelevant to the matter before the court, how many involved mutually inappropriate behaviour and how many had findings to support the allegation or that they were unfounded/fabricated. One relatively small-scale one by Professor Tommy Mackay at Strathclyde University concluded that as many as 70% of cases were found to be false or unfounded. Founder of Women’s Aid, Erin Pizzey, reported that more than half of women in the refuge she ran were in mutually abusive relationships and sometimes behaved worse than the men. We would hope that those who claim that false allegations are rare might support our call for truly independent research on a larger-scale into the prevalence and nature of false allegations and exaggerations in the context of Children Act disputes.

For now, one thing we do know is that Professor Liz Trinder, of Exeter University, carried our research that assisted the Government in its decision to table the ‘No-Fault Divorce’ Bill that is currently going through Parliament. The report quotes a range of authoritative sources e.g. The Law Commission saying that the ‘system still allows, even encourages, the parties to lie, or at least to exaggerate, in order to get what they want’. Does anyone suppose that when emotions are raw, people are angry, feel jealous and hurt, and stakes high (access and parenting time) that the propensity to lie and exaggerate might be any less?

If we then add to this cocktail that since 2013, when LASPO was introduced, a condition of qualification for Legal Aid in private family disputes was the making of allegations of domestic abuse. Whilst the majority of such claims are likely to be genuine, a significant proportion – that we estimate in thousands per year, are obtained on the basis of false allegations and exaggerations – on issues that do not then even feature in subsequent proceedings.

The statistics imply this. The growth of complaints of this amongst our service users supports this and we are now hearing of this increasingly from the judiciary too. The former President of the Family Division, Sir James Munby, said “One of the greatest vices of our system… is the unfounded allegation which festers around and poisons the process”. He should know!

Parental Alienation

Interviewed on the Victoria Derbyshire Show on 15th May 2019, Charlotte Proudman spoke of a view that “women lie” and that Parental Alienation being a “new term” that “really turns my stomach”. In her article, she suggests there is ‘scant scientific research’ into it. Except, firstly, nobody is suggesting that only women lie. Men and women can and do and it is up to the court to determine whether and who is lying. Secondly, Parental Alienation has been recognised under those terms since the ‘80s (as well as studied earlier). Thirdly, bad-mouthing and the many other behaviours that form part of what is now known as parental alienation existed well before the term was coined and were every bit as damaging. Fourthly, there is a significant and growing body of research into it and the World Health Organisation, (WHO), who don’t take decisions lightly, has just recognised it too. Whatever the research, one hopes that it is not too contentious to say that parents who enmesh the children in their feelings and paint their other parent as a monster are not putting their children’s needs first. They are doing harm to their own children that is certainly equivalent to other forms of child abuse. That, and all forms of abuse, should be a concern for all of us to jointly develop solutions for. To deny parental alienation and alienating behaviours is a danger to children.

As we are not saying that all women lie any more than all men do, neither should it be surprising that parents who are accused of abuse might seek to use parental alienation as a form of defence. The role of the court, however, has to be to use evidence to distinguish between the different causes of a child’s rejection of a parent, including undue influence by the other. A dogmatic failure to consider this possibility would in fact leave the child at risk of ongoing abuse that will damage them for life.

The reality of some 6,000 applications being made each year for enforcement of Child Arrangement Orders that have not been complied with tells its own story. As does the fact that courts often give up in these situations and make orders for Indirect Contact only i.e. sending cards, letters and gifts (see article in Family Law).

Prevalence of Abuse and How to Make Progress

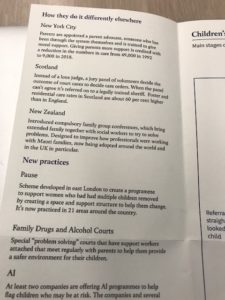

At FNF we note that there are men who are perpetrators of horrendous abuse, just as there are women who do so. Ministry of Justice data reports that around two-thirds of domestic abuse (65%) is against women and a third (35%) against men (695,000). We might also argue that there is evidence of more men under-reporting. The point is, whatever the precise figures, every victim who is being harmed deserves to be supported by the courts and other services. So does every victim of false allegations – the latter do tremendous harm too. We need to create a culture that drives out all forms of abuse against everyone. It will happen when we all seek to understand each other’s problems and reach out for balanced facts and research. That is less likely to happen if those whose voices dominate the discussions on domestic violence continue to seek to make this into a gendered debate. A divisive approach seems unlikely to succeed and real progress will happen when men support women who are victims and vice versa.

Review of Protection in Family Justice May 2019 saw the culmination of an organised, effective lobby from a number of women’s rights activists and organisations seeking a review of family justice based on a narrative suggesting that family courts are granting ‘contact at all costs’, resulting in dangerous men having unsupervised contact. This is patent rubbish. At that time 123 MPs were persuaded to sign a call for an independent inquiry into this frightful alleged occurrence. An entire one hour Victoria Derbyshire Show was dedicated to this ‘scandal’ and subsequent shows continued to address this narrative. The ‘research’ carried out by the show found four cases in the last four years where a father had killed a child whilst on contact. The problem was that it was selective and did not look at children killed by mothers – of which, sadly, there are many.

As if to highlight this point, only last week a Serious Case Review was published following the murder of a five-year-old boy, whilst on contact with his narcissistic mother on Father’s Day. She left a note to say ‘If I can’t have Leo then nobody is going to’. One of the recommendations of the report was:

‘That Kent Safeguarding Children Board and the Kent and Medway Domestic Abuse Executive Group develop an increased understanding of the needs of men as victims of domestic abuse and what this means about the nature of services that should be provided for them.’

If we are to make the world safer for children and adults alike, it will not be achieved by men and women working against each other, but in seeking to understand the underlying issues without being led by feelings, ideology and dogma. The Government rejected an independent inquiry, but did announce a more limited review. The need to create trust amongst both men and women remains. The current make-up of the review panel is 10 women and one man. It includes a representative of Women’s Aid and not one representative of men’s or fathers’ organisations or those with experience of false allegations. Consequent recommendations will affect fathers, mothers, and children including, in all probability, those where there are no domestic abuse considerations.

In summary – there is a desperate need for a review of family justice, but this narrow, gendered exercise with a very unrepresentative panel is not the right approach.