This post originally appeared on The Transparency Project but objections were raised to my use of the feature image. So I repost it here.

This post is to comment on the latest ramifications of the long journey of two parents who faced the same accusation in both criminal and family courts but with very different outcomes.

The Transparency Project commented on this case in 2016; first looking at the legal position with regard to over turning adoption orders. Julie Doughty described the factual background in June 2016, asking the question ‘can an adoption order be undone?’ (answer – yes but it’s very rare):

In … Re X [2016] EWHC 1342 (Fam), the President of the Family Division, Sir James Munby, gave permission for a full re-hearing of the original allegations made in care proceedings in 2012 involving an injury to child, now aged four, who was adopted in 2015. The problem that has since arisen is that the criminal proceedings brought against the parents, later in 2015, were dropped part-way through the trial. The trial judge directed that the parents be acquitted, as there was no case to answer. The standard of proof in a criminal case is of course higher than in a family case, but the parents now want that family case overturned. This is understandable, because if they want to have more children, or to work with children in the future, the family court finding will still say they pose a risk. However, their barrister told the President that if they were successful at the re-hearing, they would go on to challenge the adoption itself.

I also commented on this decision to hold a re-hearing in November 2016: ‘You can’t handle (51%) of the Truth’ . By October 2016 the parents were clear they did not wish to participate in any rehearing and did not wish to challenge the adoption order. They provided written statements setting out that they could not contemplate removing X from a settled home after so much time had gone by. However, the LA, Guardian and adoptive parents all wanted a hearing.

The LA accused the parents of cynically withdrawing from a case they knew they could not win. The criminal prosecution had failed not because the parents were a victim of a miscarriage of justice and had been ‘exonerated’ but because prosecution witnesses could not agree about the existence or otherwise of metaphyseal fractures; accepted by all as a difficult area of diagnosis. Metaphyseal fractures are also called ‘corner fractures’ or ‘bucket handle fractures’ as they refer to an injury to the metaphysis, which is the growing plate at each end of a long bone, like a thigh bone. Most experts agree it is a indicator of abuse as the force applied to cause these fractures is shaking. Metaphyseal fractures occur almost exclusively in children under 2 because they are small enough to be shaken and they cannot protect their limbs.

The prosecution decided, very properly, that they could offer no further evidence against the parents in light of their own experts’ lack of certainty when set against the high criminal standard of proof.

This emphasis on declaring ‘the truth’ on the balance of probabilities, troubled me then, and troubles me now. In 2016 I commented:

What I had hoped we would see would be some open, transparent and honest discussion about the often enormous and sometimes irreconcilable tensions between doing right by parents and doing right by their children. Some recognition of the unnecessarily cruel bluntness of the lack of options for children to keep in contact with birth families, when decisions are made for adopted children, and which the Court of Appeal recognised in Re W [2016] needed further thought.

However, what it looks like we may get is some dreadful pantomime, further spending of many thousands of pounds of public money in some charade that by holding a re hearing of a finding of fact on the civil standard of proof (the balance of probabilities) we will somehow get to The Truth and we must do this because it will benefit the child.

What happened after October 2016?

For reasons which are not explained, the decisions of the court made in 2016 around this re-hearing have only just been published on the BAILII website in December 2018 so we are finally able to understand how this unusual situation has resolved.

Can a hearing take place if the parents won’t participate? And what are the implications for ‘The Truth’ ?

The first issue to be determined was whether or not the parents’ refusal to participate in the new finding of fact meant it should not go ahead. The court decided it should, commenting at para 30 and my emphasis added:

The fact is that, because of everything which has happened in this most unusual litigation, we are in a very good position to know what the birth parents’ case is and how it would, in all probability, be deployed before me were they to remain participating fully in the re-hearing. So I am reasonably confident that the essential fairness and validity of the process will not be compromised by their absence, just as I am reasonably confident that, even if they play no part in it at all, the process will be able to find out the truth for X and for the public.

I have highlighted that part of the judgment as it does not reassure me that any of the points I raised in 2016 have been answered; rather my concerns have increased. This creates a situation where the child and the wider public are asked to accept that ‘The Truth’ has been discovered on a balance of probabilities, with no participation from the parents and a Judge who is then only ‘reasonably confident’ that the process will work. By the time of the conclusion of the renewed fact finding the President was on firmer footing (see para 47), and was now ‘confident’ the truth had prevailed – but this remains ‘the Truth’ only on a balance of probabilities.

The court then continued with the finding of fact over a 12 day hearing in October and November 2016. See X (A Child) (No 4) [2018] EWHC 1815 (Fam)(decided in 2016 but not handed down in open court until 14 December 2018)

The court found that the parents had hurt X and they had decided at a late stage to try to avoid a finding of fact because they knew ‘the game was up’. The (then) President commented at para 125:

…I ought to say something about the timing and asserted basis for their attempted withdrawal from the proceedings. I cannot accept their protestation that the motivation for this was concern for X’s welfare and a recognition that there was little realistic prospect, whatever my findings, of ever being able to challenge the adoption order. If that had indeed been the case, they could have sought to withdraw much earlier. The truth, as it seems to me, is that, faced with the overwhelming weight of all the expert evidence which by then had been marshalled, they realised that ‘the game was up’ and cynically sought to withdraw, hoping that this would stymie any attempt to re-visit Judge Nathan’s original findings and thus prevent those findings being vindicated…

Matters of interest: Controversial expert evidence

These proceedings touch on a number of key issues that frequently become the subject of discussion and concern about how we deal with allegations that parents have hurt children. I have already commented on the issue of the standard of proof in family proceedings above. Annie will give below her perspective as a parent on how she reacts to the potential for different outcomes on the same facts in criminal and family courts.

It also highlights the difficulties around ‘controversial’ expert evidence which we touch upon in our guidance note relating to experts in the family courts – see Part 6relating to issues of medical controversy. In the criminal court the parents instructed Dr David Ayoub, a board certified radiologist licensed to practise medicine in the United States of America in the states of Illinois, Missouri and Iowa.

He could not be persuaded to attend the renewed fact finding in 2016 so the court considered his 2015 report and the evidence given in the criminal proceedings. Dr Ayoub had taken the controversial view that metaphyseal fractures happen extremely rarely and ‘for a great deal of the time, the medical community fail to take account of rickets’. His evidence was dismissed by the court as ‘worthless’, noting the reactions of the other doctors who described Dr Ayoub’s evidence as ‘nonsense’ (see para 43)

Asked by me to amplify what he meant by “nonsense”, whether he was using it with the colloquial meaning of “bonkers” or with the meaning “lacking any sense”, Dr Somers unhesitatingly replied “both.” Dr Somers said that Dr Ayoub’s interpretation of the images was “so far removed from any competent radiological interpretation that I have encountered that I would question either motive or competence.” He said of Dr Ayoub’s report that it “obfuscates important issues with a selective interpretation of the evidence in order to support an unproven theory.”

It is worth commenting that this is quite an incredible exchange for one expert to have with a Judge about the quality of another purported expert. There are other reported examples of parents attempting to rely on ‘foreign’ experts of less than stellar reputation and I wonder whether this is the inevitable consequence of the growing distrust of ‘the system’ and belief that all experts are in the pockets of the local authority – for an interesting example of the problems this can cause note also A (A Child), Re [2013]EWCA Civ 43. For further comments and concern about Dr Ayoub, see this article from The Times on 10th December 2018,which noted that Dr Ayoub had given evidence in other cases in the UK, further claiming calls were mounting to curb ‘incompetent experts’ and growing fears about their lack of regulation or control.

Matters of interest: Should a Reporting Restrictions Order continue to conceal the parents’ identities?

it is this issue which I think is probably the most pertinent for those of us who are interested in greater openness and transparency in the family courts. We have to grapple with the possible consequences of increased transparency, particularly in light of what seems to be a prevailing journalistic culture that rests very heavily on salacious and personal details as necessary to drive a story. When other members of the Transparency Project commented on a first draft of this post they asked why had chosen not to name the parents. My response was that I had not consciously chosen not to name them – but I felt very sorry for both of them. I have no doubt that they were encouraged to act as they did by those self styled campaigners against the family court system who persistently offer parents very bad advice on the basis that the whole system is corrupt and designed to steal children. Anyone who wants to know their names will find them by following the links in this post. I still feel uneasy about naming them here, even though I know this is futile.

The parents had welcomed considerable publicity after the collapse of the criminal trial in 2015 and their names were well known. The mother gave an interview to the Daily Mirrorsaying:

People need to know this goes on and be told the truth – you can take your baby into hospital scared they might be ill and the hospital can steal your baby away from you.

Their criminal barrister was quoted in the same article as saying:

Every step of the way when people had the opportunity to stand back, look at things again and say ‘we have made a mistake’, they ploughed on instead. These innocent parents have been spared a criminal conviction and a prison sentence for a crime they never committed. But they have had their child stolen from them. Their life sentence is that they are likely never to see their baby again.”

Sadly, this comment could not be excused as excitement in the heat of the moment arising from media attention, as the barrister’s Chambers published a blog which is still on linemaking the same points and quoting the parents’ junior criminal counsel as saying

“This tragic case highlights the real dangers of the Government’s drive to increase adoption and speed up family proceedings at all costs.”

Alarmingly, the blog post claims the parents were ‘exonerated’. They were not. The prosecution offered no further evidence. This is not a positive finding that the parents were innocent of any accusations made against them. This has echoes of the unfortunate ‘exoneration’ of Ben Butler by a family court when his text messages later revealed a very different picture; sadly after he had killed his daughter.

Such claims of exoneration are awkward when read against the 2016 fact finding. X did not have rickets. There was no miscarriage of justice. X had suffered ‘really serious abuse, child cruelty’.

At para 121 the court noted.

Standing back from all the detail, the overall picture is deeply troubling. Over a few short weeks, during the first few weeks of life, and extending, I am satisfied, over some period of time before taken to RSCH, X suffered an extraordinary constellation of what, I am satisfied, were inflicted injuries for which there is no innocent explanation: the constellation of marks and bruises noted by Dr Maynard (excepting the handful for which there may be an innocent explanation); two torn frenulae; and a number of fractures to different limbs. This was really serious child abuse, child cruelty. Whoever was the perpetrator must have known that X required medical attention. Even if someone was neither the perpetrator nor present at the time when injuries were inflicted, that person must have realised, even if only as time went by, that something was seriously wrong and that X required medical attention. Yet, until the final episode of oral bleeding, neither of the birth parents made any real attempt to obtain medical assistance for X, let alone to protect X from what was going on. Whoever was, or were, the perpetrator or perpetrators, both of the birth parents carry a high measure of responsibility for what on any view were serious parental failures.

Despite the considerable public attention already upon the parents in 2016, the court at that time agreed to impose a Reporting Restrictions Order to prohibit further naming or photographs, noting that the absence of that kind of detail would reduce the amount of publicity that could risk identification of the child or adoptive parents during the second finding of fact. The matter would be considered again when proceedings were concluded and this was done at a hearing on 30th November 2018 X (A Child) (No 5) [2018] EWHC 3442 (Fam) (14 December 2018)

In light of the outcome of the renewed finding of fact, it is not surprising that the mother now wished for the RRO to continue. She had since separated from the father who did not participate in the hearing. Her lawyers argued on her behalf that the mother was:

a vulnerable woman, lacking in formal education and certainly lacking in sufficient sophistication to negotiate dealing with the press. In the aftermath of the criminal hearing, [she] quickly came to regret having been forthcoming to the media. She experienced a level of interest and unwelcome attention that she had not anticipated and with which she could not easily cope. She withdrew from any further such involvement. She learned her lesson after the damage was done, but this socially disadvantaged young woman could never have been expected to have understood the ramifications of ‘going public’ and should not now be held responsible for the actions of others, who could have been expected to have such understanding.

However the court was not sympathetic to this argument. After conducting the balancing exercise between Articles 8 and 10 the court was clear that the parents should not be shielded by anonymity. The arguments put forward by the adoptive parents and the Press Association found favour:

…that there are in the public domain two competing narratives: one, the false narrative, in which identified birth parents portray themselves as the victims of a miscarriage of justice; the other, the correct narrative, in which unidentified birth parents are shown to have wrongly portrayed themselves as the victims of a miscarriage of justice. If the RRO continues in relation to the birth parents, it will not be possible to ‘link up’ the two competing narratives and therefore not possible to demonstrate that the false narrative is indeed false. It will remain indefinitely on the internet without anyone being able to counter it and demonstrate its falsity. More specifically, the allegation (now, as we know, false) of the identified birth parents that they – two named individuals – were the victims of a miscarriage of justice will remain indefinitely on the internet without the possibility of challenge and refutation. Ms Cover and Ms Rensten seek to meet this argument by submitting that the dragon is sleeping and will not be revived unless the birth parents are now identified. Even assuming that their premise is correct, this does not meet Ms Fottrell’s point, which is that the false narrative is out there – readily accessible by anyone with access to the internet.

A birth parent’s perspective

Annie, one half of the Project Coordinator role at the Transparency Project and author of Surviving Safeguarding: a parent’s guide to the child protection process adds her perspective.

I remember this case as it unfolded in the glare of the media in 2016.

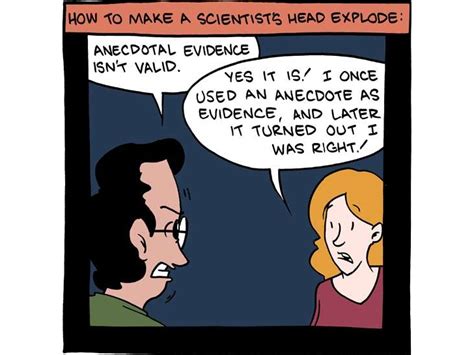

What I, and other parents read was that these parents had taken their child to hospital, quite rightly, for medical help, and were accused of harming him or her, meaning that the baby was removed from their care at six weeks old. These parents were then put through the ordeal of a criminal trial and were found innocent of harming their baby. In the meantime, the Family Court had found, on the balance of probabilities, that the child had been harmed and decided that the baby should never be returned to their (seemingly innocent) parents and forcibly adopted. After being cleared of any criminal charges, the parents launched an appeal to have that child returned, an appeal which they then withdrew from, saying that their child had been with the adopted parents so long it would not be fair to move them.

To add insult to injury, Sir James Munby, the President of the Family Court Division (as he was then) added in cynical comments saying that he thought the parents had withdrawn because they “knew the game was up”. He stood by the family court findings (that the child was harmed by the parents).

I, like many birth parents with experience of the child protection system, felt both confused and angry by what I was reading. I felt angry with Munby and defensive towards the parents. How could birth parents who had been found innocent of abusing their child still go on to lose that child to a non-consensual adoption? It seemed utter madness – and a terrifying concept. Since 2015, I have offered direct advocacy to birth parents embroiled in the child protection process. What was I supposed to say to a parent who came to me, frightened, and not engaging with the local authority as a result, who had read this story in publications like the Daily Mail? How was I to reassure them that if they engaged with the help being offered that they had a far better chance of their family staying together when this story was being splashed all over the news and shared in amongst Facebook groups set up to protest against forced adoption? And quite frankly, who could blame these parents for feeling scared? I was, too.

I’ve since read the judgments, and taken time to review what evidence is available in the public domain. I understand better, and my view has changed. However, in the main, most members of the general public don’t read judgments. In the main, we read the news reports and form our opinions from them.

When it comes to parents involved with Children’s Services, these news reports only serve to exacerbate our fears that social workers are the “bogeymen” who will steal our children, even when we are found innocent. This perpetuates the “them and us” narrative, and means we are far less likely to either ask for help, or engage with the help being offered to safeguard children.

Conclusions

Sir James Munby’s confidence that the ‘true’ narrative will now overpower the false one, perhaps displays too great a faith in the ability of people to readily abandon narratives that chime with their own emotional reactions when presented with ‘facts’ (particularly if these are facts established as likely only on 51%). Publishing information on the internet does not by itself remedy the harms caused by adherence to more general conspiracy theories; a matter I have discussed in more detail at the Child Protection Resource.

However, this case with its harrowing and hopefully very unusual set of circumstances, sets out some powerful lessons. I think it is a continuing reminder of the need to be honest about what findings of fact in court can achieve. They are rarely about ‘exonerating’ or ‘damning’ but rather making a finding on a particular standard of proof. That means we need good quality evidence and experts who adhere to good standards of practice. Although Sir James was at the end ‘confident’ that ‘the truth’ had prevailed, the situation as highlighted in the criminal proceedings remained; the images of the fractures were of poor quality and the experts were not unanimous about what they saw.

As Annie comments above, it is a very clear example of just how confused those are outside the system about how it operates. The different standards of proof in criminal and civil cases is rarely understood, and when it is many parents make the reasonable comment that if their child is going to be adopted, it should be on the higher standard of proof.

However, most compellingly of all in my view, this case is a reminder of that he genie cannot be put back in the bottle. If we are pushing for greater openness and transparency, we all need to be mindful of the possible consequences. Once information is ‘out there’ it is very difficult to control how it will be republished or reinterpreted, no matter how hard you insist yours is the ‘right’ version. Once you have got journalists excited about the intimate details of your case, you may well attract more attention than you bargained for and end up the centre of a story that you had not anticipated.

Possibly parents who have greater faith in a court system will be less likely to seek to use journalists to fight their cause. But the risk of people pushing a false narrative with intent to deceive will remain and we are naive to think that publishing ‘the facts’ at a later stage will undo all the damage.

Feature Pic courtesy of Michell Zappa on Flickr (Creative Commons licence) – thanks!