The first performance took place on 28th September at the Arnolfini in Bristol and the second will be taking place in London on 28th October 2017 – see here for further details and how to register for tickets.

I have written before about the process of preparing for the performance and want to take some time to consider the feedback from the Arnolfini – did we meet our objectives of ‘having an intimate conversation’ with the audience, did we succeed in showing the audience another perspective on an area they might not have thought much about before? Were we able to empower others to take this conversation into other areas of their lives and to continue this very necessary discussion?

My feedback

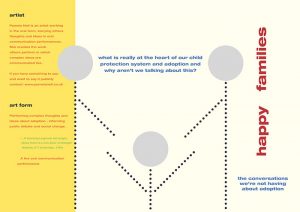

I wanted to ask the following questions – because I don’t know the answers and I don’t think we are collectively having open and honest discussions about these issues:

- Can we make happy families?

- Can we impose identity on a child?

- Do we need to ‘rescue’ children or should we be trying to support unhappy families?

- What is really at the heart of our child protection system and adoption and why aren’t we talking about this?

I was surprised how nervous I felt during the dress rehearsal – it was the first time using the actual space where the performance would take place. However, I was pleasantly surprised by how that anxiety diminished once the audience were actually there and even more pleasantly surprised by how the conversation developed afterwards.

Now, instead of dreading the London performance, I am in fact looking forward to it and to have a further arena for discussions. Because, and rather obviously, we will never get answers to questions if we don’t ask them.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BZWwcE1B-Zu/?taken-by=sarah_phillimore

Pamela Neil on stage during dress rehearsal

Feedback from others

After the performance, Pamela Neil,the artist I collaborated with to create the performance, contacted those who had attended for feedback. We are very grateful for all the thoughtful comments and will give some thought to how best to respond and incorporate any changes into the London performance.

The following are some of questions posed and the text in bold are some of the responses.

- What did you enjoy? the chance to hear some familiar concepts developed at a pace that i could absorb differently to their normal context (when sarah and I are cross and ranting to one another about the situation)

- Are your ideas about adoption different now, following the performance? actually yes, pushed slightly further along the spectrum than i was from enthusiastic to worried

- Has the performance inspired you to engage with the problem discussed? yes. i am already engaged with it, as i suspect were most of the audience, but it was helpful to look at things from a new angle. I found the analogies helpful.

- If you could suggest one change to enhance future performances, what would it be? to let the audience know what was expected in terms of questions and participation at the end. I think only those who knew sarah felt empowered to participate. I don’t know how you could better manage that and the fact that some were quite pushy in terms of ensuring that the conversation is with new people not just those who are already part of it – other than by explicit invitation.

One attendee echoed that last concern about how people can be empowered to join in the conversations:

I was hoping for a conversation about the possibility of co-parenting and whether FDACs were a good model to follow but the after-show conversation felt exclusive and I didn’t say anything. I didn’t know who was speaking, what the issues were, nor the previous history between Sarah and the speakers, although I could feel the tension. I think it would have been helpful if speakers had been invited to introduce themselves and the organisations they were representing. I was watching people’s body language during the performance and saw lots of discomfort – I hoped social workers, if there were any there, would speak out at the end and perhaps they did but I left when I felt it was a private conversation that was re-hashing old arguments rather than discussing a way forward.

We clearly need to give some thought as to how to avoid any impression that what is happening is a ‘private conversation’ – this may be an inevitable consequence of holding the first event in Bristol where the audience were more likely to know me. Hopefully a London audience can be more diverse and conversations can be less about historic tensions and more about fresh perspectives.

However, this commentator did find the performance valuable:

There was lots of food for thought and I wanted to thank Sarah; it is good to hear other perspectives – our focus can become too narrow. I hope it will encourage the different systems to work together more closely and explore alternative ways of looking after children perhaps based on evidence from other countries.

I hope that the conversations can continue in London on October 28th.