What can I do?

it will depend at what stage of the proceedings you have reached and what orders have already been made. A child can only be adopted when three orders have been made – a care order, a placement order and finally, an adoption order. Care and placement orders are usually made at the same time.

- A care order allows the State to decide where your child should live and who spends time with him or her.

- A placement order allows the State to put your child with a family that may decide to adopt him or her.

- An adoption order confirms that this family is now the legal family and the birth parents no longer have any legal connection to their child.

So which situation are you in? This post will discuss only the LAST TWO. If you want to challenge a care order – see this post.

- Parents are currently in care proceedings and no final order has been made It is really important that parents argue their case in the care proceedings while they are happening – you need to engage with the case against you at the time as it may be too late to do anything to change the situation once a care order is made.

- Final care order made but no placement order. If a placement order hasn’t been made yet, you may be able to appeal against the care order or apply to discharge it.

- Final care order and placement order made – Parents can apply for leave to revoke a placement order under section 24 of the ACA 2002, IF:

- their child hasn’t yet been placed for adoption; and

- they can show a ‘change of circumstances’ since the placement order was made.

- The form to make an application to revoke a placement order is here.

- The court has confirmed that a Judge should look at the welfare checklists in both the Children Act and the Adoption and Children Acts when making decisions about these cases

- Potential adoptive parents have applied for an adoption order – Parents can apply for permission to contest the making of an adoption order under section 47(7) of the ACA 2002 but only if they can show a ‘change of circumstances’.

- The adoption order has been made – can I overturn it? – this is rare but possible. See discussion below.

Challenging an application for an adoption order

Don’t waste time

Remember – UK law is compatible with the ECHR

It is always better to make your challenges and objections during the care proceedings. It is essential to challenge a care order as soon as possible if you do not consider it was validly made – it is too late to wait until the time that applications are made to apply for adoption.

Don’t waste time arguing that UK law is not compliant with international law. In the case of G (A Child) [2017] EWCA Civ 2638 (08 November 2017) the father wanted the court to declare that the Adoption and Children Act 2002 was not compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. The Court of Appeal referred to Re CB (A Child) (No. 2) (Adoption Proceedings: Vienna Convention) [2016] 1 FLR 1286 in which Sir James Munby President said at paragraph 83:

“The second point is that, whatever the concerns that are expressed elsewhere in Europe, there can be no suggestion that, in this regard, the domestic law of England and Wales is incompatible with the UK’s international obligations or, specifically, with its obligations under the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms 1950. There is nothing in the Strasburg jurisprudence to suggest that our domestic law is, in this regard, incompatible with the Convention. For example, there is nothing in the various non-consensual adoption cases in which a challenge has been mounted to suggest that our system is, as such, Convention non-compliant.”

If you are arguing about the care proceedings when faced with adoption order – you’ve already lost

There is a useful and clear discussion about the process in the case of A and F (children) [2015] where a mother argued that her children should not be adopted but this argument was based on an assertion that the care orders should not have been made in the first place. Therefore, she did not accept that any criticism could be made of her parenting and she was unable to engage with the essential steps to challenge her children’s adoption – that she must show ‘a change of circumstances’

As the Judge commented at para 26 of his judgment:

Indeed, the majority of the mother’s statement is concerned with the repetition and correction of perceived past wrongs sustained by her. This was also the position with regard to her oral submissions. This means that inevitably she does not accept as a “starting point” District Judge Shaw’s decision nor his findings. As a matter of logic, therefore, she finds it impossible to address the issue of “changes in circumstances” because broadly her parenting circumstances, when the children were removed, were perfectly acceptable and therefore no change is required. Accordingly, an intellectual impasse results.

So what do you have to do?

- Step One: establish a change of circumstances. The court has already decided by making a final care order that the parent has caused or is likely to cause a child significant harm. Therefore the parent must show the court what is different NOW. This is discussed in more detail below;

- Step Two: convince the court it is right to give permission to argue against an adoption order being made. This means that the court will look at all the relevant issues in the case and think about what the impact would be on the children. The children’s welfare is the most important consideration for the court. If the parent doesn’t succeed in getting permission, the matter ends there.

- Step Three: Persuade the court to refuse an adoption order IF a parent is given permission to argue against the making of an adoption order, they will have to persuade the court to reverse the direction in which the children’s lives have travelled since the Care and Placement proceedings. Obviously, the longer the children have been in their potential adoptive placement, the harder this will be.

Although the courts try to separate out the different questions, to make it easier to analyse the issues, it is clear that each question has the potential to be significantly wrapped up in the other questions. For example, the ‘prospect of success’ the court is looking at refers to your prospect of success in challenging the order, NOT your prospects of success in getting your child home.

However, if you have very little chance of persuading the court that the child should come home, that issue is certainly going to be on the court’s mind. It is very difficult to successfully challenge placement or adoption orders, as by the time such challenge is made the child has been living away from the parents for many months, even years and the court is going be worried about the impact on the child of possibly another move from a home where they may now be settled.

In Re L [2014] 2FLR 913 at paragraph 45, Lady Justice Black said this:

“When a judge considers a parent’s prospect of success for the purposes of section 47(5), he is doing the best he can to forecast what decision the judge hearing the adoption application is going to make having the child’s welfare throughout his life as his paramount consideration. What is ultimately going to be relevant to the decision whether to grant the adoption order or not must therefore also be material at the leave stage.”

STEP ONE – what does ‘change in circumstances’ mean?

It’s a matter of fact and it has to be relevant. Case law gives us the following principles :

- The test should not be so difficult that it rules everyone out – parents shouldn’t be discouraged from trying to improve their lives.

- The changes must be relevant to the question of whether or not leave should be granted – for e.g. if the worry was originally that you drink too much, have you stopped or cut down?

- The changes are not confined to those of a birth parent, but they may include changes occurring in the child’s life (see Re T [2014] EWCA (Civ) 1369).

- The necessary change in circumstances … does not have to be “significant”; the question is whether it is “of a nature and degree sufficient, on the facts of the particular case, to open the door to the exercise of the judicial discretion to permit the parents to defend the adoption proceedings”: Re P (Adoption: Leave Provisions) [2007] EWCA 616, [2007] para 30 – discussed in Re T [2014] in context of applying to revoke a placement order.

There is a useful article here by suesspiciousminds which considers the relevant case law in this area, and in particular the case of The Borough of Poole v W [2014] EWHC 1777. The Judge concluded at paragraph 25 of his judgement that the parents could not succeed, despite making considerable changes to their lives:

I have considered this case with the most anxious care, considering how much is at stake, both for parents and prospective adopters who happily all have a real understanding of each other’s predicaments. However, above all what is at stake for SR? There can be no blame attached to any of the four adults for why we have all ended up where we have. Nevertheless, a decision of profound significance has to be made. In the end, I have reached a clear conclusion that there is only one route which will sufficiently safeguard the welfare of SR and that is the route of adoption.

My real concerns about SR’s ability to survive the process of rehabilitation and the parents’ ability to sustain her care, whatever her reactions throughout her childhood, when seen in the context of their fragility and of the consequences to SR of a failure of rehabilitation and the need to then start all over again. All those matters when drawn together, in my judgment, require that adoption be provided as the way of securing her welfare and therefore require that the court dispenses with the parents’ consent. In making the order which, in my judgment, promotes the welfare of SR, I fully recognise the grief of the parents who do not share my view and I recognise that I have no comfort to offer them, beyond letterbox contact. If ever an example was needed of how legitimate and heartfelt aspirations of parents can be trumped by the welfare needs of the child, this surely is it.

For an example of a case where a mother succeeded in appealing against the initial refusal to allow her to argue against a placement order, see the case of G (A Child) [2015] EWCA Civ 119, discussed in this post by suesspiciousminds. The Court of Appeal agreed that a change to the child’s circumstances could also be relevant:

The “change in circumstances” specified in section 24(3) of the 2002 Act is not confined to the parent’s own circumstances. Depending upon the facts of the case, the child/ren’s circumstances may themselves have changed in the interim, not least by reason of the thwarted ambitions on the part of the local authority to place them for adoption in a timely fashion. I would regard it as unlikely for there to be many situations where the change in the child’s circumstances alone would be sufficient to open the gateway under section 24(2) and (3) and I do not suggest that there needs to be an in-depth analysis of the child/ren’s welfare needs at the first stage, which are more aptly considered at the second , but I cannot see how a court is able to disregard any changes in the child/ren’s circumstances, good or bad, if it is charged with evaluating the sufficiency of the nature and degree of the parent’s change of circumstances.

The case of P (A Child) [2018] EWCA Civ 1483 (28 June 2018) allowed a mother’s appeal against the refusal to grant her an adjournment before making a placement order. Although there had been long standing concerns about her alcoholism, she had developed considerable insight and made significant progress – she had done ‘all’ that could be expected of her. The Court of Appeal rejected the suggestion that a six month adjournment served ‘no purpose’ given that the plan for a 6 month old baby was adoption.

Further reading about ‘change of circumstances’.

- See this post from the UK Human Rights blog – Challenging Adoption order using Human Rights.

- For an example of a case where an appeal against an adoption order did not succeed,see R (A Child) [2014]

- For a case discussing what happened when a parent wanted to contest an adoption order by asking the court to look at fresh evidence, see the case ofG (A Child) [2014].

- See C (Revocation of Placement Orders) [2020] EWCA Civ 1598 (27 November 2020) and discussion of the case by The Transparency Project. Even a mother who was said to have made a ‘remarkable transformation’ to her life did not succeed in challenging the adoption of her three children.

- See also M (A Child: Leave to Oppose Adoption) [2023] EWCA Civ 404 which highlights the importance of getting a transcript of the judgment which is challenged as soon as possible.

STEP TWO: If there is a change of circumstances, should the court give you permission to challenge the adoption order?

In relation to Step two this an issue of judicial evaluation or discretion which means that different judges can and do make different decisions but could not necessarily be challenged on appeal. ‘Exercising a discretion’ means you are making your own value judgment and there is usually a pretty wide range of possible outcomes that would be accepted. Provided of course that the Judge has applied the correct law and facts.

The parent must have ‘solid grounds’ for making the application. Paragraph 74(i) to (x) of Re B-S identifies the features to be weighed in the balance.

- Prospect of success here relates to the prospect of resisting the making of an adoption order, not the prospect of ultimately having the child restored to the parent’s care.

- The issues of ‘change in circumstances’ and ‘solid grounds for seeking leave’ are treated as two separate issues in order to analyse them BUT in reality they are inter-linked and one may follow the other

- If the Judge finds a change of circumstances AND solid grounds for seeking permission, the Judge must then consider child’s welfare very carefully.

- The judge must keep at the forefront of his mind the teaching of Re B, in particular that adoption is the “last resort” and only permissible if “nothing else will do” and that, as Lord Neuberger emphasised, the child’s interests include being brought up by the parents or wider family unless the overriding requirements of the child’s welfare make that not possible.

- But, the child’s welfare is paramount.

- To find out what the child’s welfare needs, the judge must take into account ‘all the negatives and the positives, all the pros and cons, of each of the two options, that is, either giving or refusing the parent leave to oppose. The use of Thorpe LJ’s ‘balance sheet’ is to be encouraged.

- The court needs proper evidence, but this doesn’t always have to be evidence from people speaking to the court. Often applications for leave can be fairly dealt with on written evidence and submissions.

- As a general proposition, the greater the positive change in circumstances and the more solid the parent’s grounds for seeking leave to oppose, the more significant must be the detrimental impact on the child if the court is going to refuse to give them permission to challenge the adoption order.

- The fact a child is now living with the prospective adopters or that a long time has passed, cannot determine the matter.

- BUT the older the child and the longer he/she has been living with the prospective adoptions, the worse it is likely to be to disturb that.

- The court should not attach too much weight to any argument that the proceedings are having an adverse impact on the prospective adopters – but this isn’t a trivial point and judges must try to minimise this impact by robust case management.

- The judge must always bear in mind that what is paramount in every adoption case is the welfare of the child “throughout his life”.

Given modern expectation of life, this means that, with a young child, one is looking far ahead into a very distant future – upwards of eighty or even ninety years. Against this perspective, judges must be careful not to attach undue weight to the short term consequences for the child if leave to oppose is given. In this as in other contexts, judges should be guided by what Sir Thomas Bingham MR said in Re O (Contact: Imposition of Conditions) [1995] 2 FLR 124, 129, that “the court should take a medium-term and long-term view of the child’s development and not accord excessive weight to what appear likely to be short-term or transient problems.” That was said in the context of contact but it has a much wider resonance: Re G (Education: Religious Upbringing) [2012] EWCA Civ 1233, [2013] 1 FLR 677, para 26.

The court will be well aware of the seriousness of adoption and the decision of the Supreme Court in the case of Re B [2013] 1WLR 1911.

See also W (A Child: Leave To Oppose Adoption) [2020] EWCA Civ 16 (21 January 2020) where the appeal court agreed the parents should be given permission to argue against the making of an adoption order.

STEP THREE: Will the court reverse the ‘direction of travel’ for the child and refuse to make an adoption order?

It is quite rare for the court to refuse to make an adoption order. One example of such a case is A and B v Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council [2014] which is the first since the 2002 Adoption Act. The court removed the child from the home of the potential adoptive parents – where he was settled – to live with his paternal aunt. It is clear that the court must consider the child’s welfare throughout his life – as the Judge commented here, this could mean 80 years or more.

The Judge commented at paragraph 95:

This case clearly requires taking both a short term and a long term view. C is currently very well placed with “perfect adopters”. They are a well trained couple with whom he is very well attached. He is of mixed race. They are both white and share with him that half of his ethnicity. A and B are “tried and tested” as has been said. His aunt and the principal members of the paternal family are black and share with him that half of his ethnicity. The aunt is a single person. She has not been “tried and tested” as a carer for C, but she has been observed as a carer of her own child, G, and thoroughly assessed as entirely suitable to care long term for C. There would be likely to be short, and possibly long term harm if he now moves from A and B to the aunt, but that is mitigated by his embedded security and attachments with A and B, and can be further mitigated by specialist training and support for the aunt, which she will gladly accept. The unquantifiable but potentially considerable advantage of a move to the aunt is the bridge to the paternal original family.

It is my firm judgment and view that it is positively better for C not to be adopted but to move to the aunt. In any event, I certainly do not consider that making an adoption order would be better for C than not doing so. Accordingly I must, as I do, determine not to make an adoption order and must dismiss the adoption application. Pursuant to section 24(4) of the Act, I exercise a discretion to revoke the placement order made in respect of the child on 2 August 2013.

The Judge had this to say about the ‘nothing else will do’ test at paragraph 15:

With so many Article 8 rights engaged and in competition, it does not seem to me to be helpful or necessary in the present case to add a gloss to section 1 of only making an adoption order if “nothing else will do”… Rather, I should simply make the welfare of the child throughout his life the paramount consideration; consider and have regard to all the relevant matters listed in section 1(4) and any other relevant matters; and make an adoption order if, but only if, doing so “would be better for the child than not doing so”, as section 1(6) requires.

If the balance of factors comes down against making an adoption order, then clearly I should not make one. If they are so evenly balanced that it is not possible to say that making an adoption order would be “better” for him than not doing so, then I should not do so. If, however, the balance does come down clearly in favour of making an adoption order, then, in the circumstances of this case, I should make one. I do not propose to add some additional hurdle or test of “nothing else will do”.

The decision of the Court of Appeal in July 2016 in W (A Child) [2016] EWCA Civ 793 dealt explicitly with four very important questions:

- The approach to be taken in determining a child’s long-term welfare once the child has become fully settled in a prospective adoptive home and, late in the day, a viable family placement is identified;

- The application of the Supreme Court judgment in Re B [2013] UKSC 33 (“nothing else will do”) in that context;

- Whether the individuals whose relationship with a child falls to be considered under Adoption and Children Act 2002, s 1(4)(f) is limited to blood relatives or should include the prospective adopters;

- Whether it is necessary for a judge expressly to undertake an evaluation in the context of the Human Rights Act l998 in such circumstances and, if so, which rights are engaged.

The court said this about the ‘nothing else will do’ test at paragraph 68 of their judgment:

Since the phrase “nothing else will do” was first coined in the context of public law orders for the protection of children by the Supreme Court in Re B, judges in both the High Court and Court of Appeal have cautioned professionals and courts to ensure that the phrase is applied so that it is tied to the welfare of the child as described by Baroness Hale in paragraph 215 of her judgment:

“We all agree that an order compulsorily severing the ties between a child and her parents can only be made if “justified by an overriding requirement pertaining to the child’s best interests”. In other words, the test is one of necessity. Nothing else will do.”

The phrase is meaningless, and potentially dangerous, if it is applied as some freestanding, shortcut test divorced from, or even in place of, an overall evaluation of the child’s welfare. Used properly, as Baroness Hale explained, the phrase “nothing else will do” is no more, nor no less, than a useful distillation of the proportionality and necessity test as embodied in the ECHR and reflected in the need to afford paramount consideration to the welfare of the child throughout her lifetime (ACA 2002 s 1). The phrase “nothing else will do” is not some sort of hyperlink providing a direct route to the outcome of a case so as to bypass the need to undertake a full, comprehensive welfare evaluation of all of the relevant pros and cons (see Re B-S [2013] EWCA Civ 1146, Re R [2014] EWCA Civ 715 and other cases).

The court was clear that there is NO ‘presumption’ or ‘right’ for a child to be brought up by natural family and that those assessing the case had wrongly believed there was – thus the focus on the impact of removing A from the only parents she had known for 2 years, was not properly considered.

The issue is only and always the child’s welfare. The matter was returned to another judge for a re-hearing. It will be interesting to know the outcome.

Time Limits for Appeals.

For more detailed discussion of the rules that apply to time limits, see this post about appealing against a care order. It is very important that you tell the court that you want to appeal and why you want to appeal within 21 days of the decision you want to challenge.

The court have considered appeals out of time in the case of re H (Children) [2015] and emphasised how important it is to stick to time limits in children cases. Although the father in this case was allowed to appeal some 8 months after the first decision, the court emphasised that this was ‘exceptional’. See paras 33 and 34 of the judgment:

33.As a matter of law, if no notice of appeal is lodged during the 21 days permitted for the filing of a notice, a local authority should be entitled to regard any final care order and order authorising placement for adoption as valid authority to proceed with the task of placing the child for adoption. If that process has subsequently to be put on hold in order to allow a late application for permission to appeal to be determined, the impact upon the welfare of the child (particularly where prospective adopters who have been chosen may be deterred from proceeding) is also too plain to contemplate.

34. The problem that I have described is a necessary difficulty that arises from our system which contemplates that, notwithstanding the expiry of the 21 day period for lodging a notice of appeal, the court may, where to do so is justified, permit an appeal to proceed out of time. There will thus inevitably be a period after a late application for permission to appeal where time is taken to process the application before it is determined. Whilst accepting the inevitability of this source of, in some cases, highly adverse impact on the welfare of a child, every effort should be made to avoid its occurrence. One strategy which would seek to avoid the problem would be for the judge in every case where a final care and placement for adoption order is made to spell out to the parties the need to file any notice of appeal within 21 days and for the resulting court order to record on its face that that information was given to the parties by the judge. Secondly, this court and any appellate judge in the Family Court, must continue to strive to process any application for permission to appeal in a public law child case with the utmost efficiency. Finally, the fact that an application for permission to appeal which relates to a child in public law procedure is out of time should be regarded as a very significant matter when deciding whether to grant ‘relief from sanctions’ or an extension of time for appealing.

The adoption order has been made – can I challenge it?

This is very rare – but possible. However, those cases where adoption orders have been overturned appear to rest on procedural flaws in the application, not on the merits or otherwise of the adoption. The Websters for example, were denied the opportunity to challenge the adoption of their children on the basis that the children had lived apart from them for so long, it would not be in the children’s interests to remove them from their adoptive homes.

The case of, ZH v HS & others [2019] EWHC 2190, gives a clear example of how mistakes made in how the adoption order was applied for and made, were so serious that they undermined the whole basis for the order and it was set aside.

T and her mother ZH tried to come to the UK from Somalia to claim asylum .T ended up with the maternal aunt and uncle who asked social workers to help them regularise T’s status with them. They didn’t get legal advice but went to a CAB and filled in the forms to make an application to adopt T, saying ZH was missing – as they didn’t know where she was. T’s mother then managed to enter the UK two years later. She was clearly out of time to appeal against the making of an adoption order so she applied under the court’s inherent jurisidiction to set it aside. Every one agreed by the time this got to court in 2019, this was the right thing to do and T should be looked after by her mother.

The court was very critical about how the adoption order ever came to be made, calling the process ‘flawed’ and ‘replete with errors and omissions’, not least the correct notice wasn’t given to the LA and there were no checks on the uncle and aunt and no guardian appointed for T.

It is indeed really worrying to think that such an application got through a court process without anyone apparently noticing such significant procedural failings and there is no surprise that the High Court found these errors were so serious they tainted the whole process; the adoption order could not stand.

However, we are waiting for the Court of Appeal’s full judgment on another case where a mother has attempted to use the inherent jurisdiction to over turn an adoption order – her appeal was dismissed in June 2021 and it will be interesting to read the full reasons.

See further Julie Doughty’s discussion at The Transparency Project, ‘Can an adoption order be undone?’

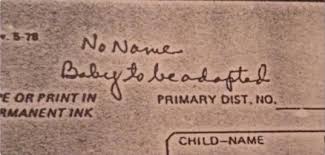

I have taken the photograph above from this blog post – How does it feel to be adopted?