I was recently contacted by the journalist Beatrix Campbell with a link to an address by the President of the Family Division Sir Andrew McFarlane to the British Society of Paediatric Radiologists. He said this about the Cleveland Inquiry, which has loomed large over family lawyers for the last 30 years. Speech by the PFD: Suspected Physical Abuse of Children – Experts in the Family Court – Courts and Tribunals Judiciary

I suspect that those in the audience, like me, had understood what had happened in Cleveland arose from misdiagnosis by the two paediatricians. In that regard a recent book by journalist Beatrix Campbell ‘Secrets and Silence’ may be of interest. All these years later, with the ability to inspect previously confidential documents in the National Archive, the book explains that most of the children were probably the victims of sexual abuse, and therefore the diagnosis by medical professionals was likely to be correct. The book reveals a lack of transparency which has had lasting impacts. As a result, there as been a continuing false belief that the Cleveland children did not experience sexual abuse and that the crisis was a result of over-zealous and incompetent practice.

I was dismayed to learn that I too had internalised those two false narratives, of no abuse and professional incompetence, if slightly reassured that they were shared by none other than the President.

Back to Basics – what was the Cleveland Inquiry?

Campbell invited me to consider this. I agreed it was important. So back to basics. Sadly the Cleveland Inquiry report is not available on line. The best I could find was a useful summary published by the British Medical Journal 190.full.pdf

The report of Lord Justice Butler-Sloss on her inquiry into child abuse in Cleveland was published on 6 July (HMSO, Cm412).It was initiated in July 1987 following a ‘crisis’ where 125 children were diagnosed as having been sexually abused, thus overwhelming local police, hospitals and children’s services. 98 children were eventually returned home and 27 wardship cases were dismissed.

In June 1986 Susan Richardson had been appointed to the new post of ‘child abuse consultant’ in Cleveland. In January 1987 Dr Higgs began working there as a consultant paediatrician and the two began working closely together.

In early 1987 Dr Higgs found 10 out of 11 children who had lived in one foster placement showed signs of anal abuse and were admitted to hospital. The director of social services Mr Bishop became concerned at the scale of this development. By the end of April a rift developed between Dr Higgs and the police, who did not agree with her diagnoses. The police expressed particular scepticism about the value of reflex anal dilation [RAD] as a diagnostic sign. Mrs Richardson continued to support Dr Higgs and by June ‘unprecedented numbers’ of children had been admitted to hospital under ‘place of safety orders’.

The police and social workers continued to diverge in their approach; the police expressing caution and requiring substantial corroboration, Mrs Richardson requiring routine place of safety orders and suspension of parental contact with the children in case they interfered with the children’s ‘disclosure’.

By June two further waves of admission stretched ‘accommodation and nursing services to breaking point’, parents formed a protest group and media attention ensued. As Anna Glinski the Deputy Director of the Child Sexual Abuse Centre described it Setting the story straight on Cleveland | CSA Centre

A public outcry followed, involving local politicians, local and national media, parents, and professionals from different agencies with safeguarding responsibilities, who could not accept that so many children had been sexually abused. The result was local and national hysteria and panic that over-zealous practitioners were wrongly identifying child sexual abuse. Then the professional judgement of those working with the children was challenged.

The Cleveland report itself did NOT make any findings as to whether the children were in fact abused. It focused on procedures, acknowledging the dedication and commitment of Dr Higgs and Mrs Richardson. But various pressures led to a breakdown in communication between agencies and one of the most worrying features of what went wrong was the ‘isolation and lack of support for parents’

Dr Higgs was found to have placed undue reliance on physical signs alone of sexual abuse, in particular the RAD test and too fixed in her belief that children should be separated from their parents to permit ‘disclosure’. The BMJ described it as ‘her relentless pursuit of her goals, which never seemed to be interrupted by a pause for thought, caused unnecessary distress to children and their families’.

Lady Butler Sloss spoke to Campbell 30 years later; her view was that the doctors had ‘jumped the gun’, which destroyed the credibility of other evidence and led to premature removal of the children.

In essence, this was about disagreements and failure of communication of adults in different departments which had been allowed to obscure the needs of children. The interagency ‘squabbles’ become increasingly personal, not assisted by the bias of some of the media coverage.

One criticism of Dr Higgs was that she failed to recognise the inadequacy of resources in Cleveland to meet the crisis. This is troubling. Of course, we cannot ignore the reality of lack of resources, but this reality should not influence the outcome of an assessment of whether or not a child has suffered or is at risk of suffering harm.

The inquiry was set up to look at processes and could not evaluate the accuracy of ‘diagnostic techniques’ in sexual abuse of children. However, only 18 of the 121 children were ‘diagnosed’ on the basis of anal dilation alone. Nor did the inquiry discredit it as a technique. 27 out of the 29 experts who gave evidence considered RAD to be relevant to the recognition of sexual abuse. It was abnormal and suspicious, requiring further investigation but is not in itself evidence of anal abuse. Constipation could also be a cause.

Of the recommendations made by the Inquiry, the BMJ considered the most important

- the requirement to recognise the child is a person not simply an object of concern and adults should explain to children what is happening and not make promises that can’t be kept.

- Children should not be subject to repeated examinations or confrontational ‘disclosure’ interviews for evidential purposes.

- No one person or agency should make a decision in isolation as to whether a child has been sexually abused.

- The speed and level of any intervention planned should be considered very carefully.

- The medical ‘diagnosis’ should not be the prime consideration except in straightforward cases.

I agree with all of that. It was true in 1987, it is true and vital in 2024. So where are we now?

The legacy of Cleveland

Campbell has done important work investigating the National Archives to uncover information that shows between 70-90% of the 121 cases, the ‘diagnosis’ of sexual abuse was correct (see Treasury Official R.B. Saunders memo to Chief Secretary John Major 5 July 1988). The figure of 98 children who went home given at the time did not clarify how many abusers had been removed from the home prior to return

However, Campbell also discovered documents recognising that identifying the correct numbers of children abused was ‘dangerous territory’ as it could result in demands for more money and resources. This is shocking. Campbell’s over arching narrative is that this desire to save money rather than children has infected safeguarding practice ever since.

Anna Glinski on reviewing Campbell’s book, notes 3 ‘myths’ that she is concerned Cleveland cemented

- children commonly make false allegations

- children can easily be ‘led’ by professionals and

- that sexual abuse by a family member is rare.

As a family practitioner who stared her law degree in September 1989 I have grown up in the shadow of Cleveland – and the Orkneys which followed. I accept I had internalised a false belief that most of the children at Cleveland had not been sexually abused and the doctors had been incompetent.

I accept that far more children are sexually abused that services identify, or that we would like to think. Scale & nature of abuse | CSA Centre . It has taken us a long time to accept that children were physically abused in their homes, recognition of sexual abuse has lagged even further behind.

I accept that children at risk of harm do not the resources they need and this has been obvious in the lack of residential care and mental health provision for decades. It is scandalous that the contemporaneous discussions about funding showed a deliberate plan to direct attention away from sexual abuse of children.

However, I do not think it is correct or helpful to extrapolate from this the assertion that the Cleveland Inquiry created enduring ‘myths’ about false/exaggerated allegations and the suggestibility of children that has ‘stunted’ child protection for decades. Far from it. I see very worrying evidence about the growth of various lobby groups who would appear to wish to do away with any forensic process entirely once an allegation of abuse is made.

I cannot usefully comment on the rate of ‘false allegations’ as deliberate lies told by older children, other than to say that has been rare in my practice over 30 years, no more than a handful of cases.

However, the suggestibility of young children is well established along with the ‘impossible’ allegations younger children make. As examples from my own practice, the little girl aged 3 who was confident that the police officer interviewing her lived under her bed, or the little boy aged 5 who asserted his father dressed up as a wolf and stabbed his bottom with scissors, in the absence of any medical evidence at all. I am afraid that ABE interviews (Achieving Best Evidence) continue to be of poor quality and often opportunities lost.

Campbell dismisses any suggestion that children lie, fantasise or that their evidence can be contaminated as ‘fables’ and that to allege parental alienating behaviours is simply ‘playing a card’. My 30 years as a family lawyer shows me beyond doubt that parents – mothers and fathers – can act deliberately to influence children against the other parent. In my experience children say things that are not true and they can be influenced to say them.

Campbell rather skates over the US ‘Satanic Panic’ of the 1980s, which in my view highlighted most alarmingly the dangers of exposing suggestible children to over zealous investigators. She mentions the McMartin day care case and its ‘alarming’ medical signs of gross abuse. But I am not sure what medical evidence Campbell is relying on; I note that in 1986 the Attorney General dropped charges against five of the defendants, saying the case was ‘incredibly weak’. No convictions ensued of the remaining defendants.

Margaret Kelly Michaels of the Wee Free Day Care is not mentioned by Campbell. She was sentenced to 47 years in 1988 but freed after 5, the New Jersey Supreme Court declaring that the interviews of the children which convicted her, were highly improper and utilised coercive and suggestive methods.

Campbell considers the ‘Satanic Panic’ cases are credible, and the children might be reporting ‘real events’ as we can see from David Aaronovitch’s response SATANIC ABUSE: A REPLY TO BELIEVERS – BarristerBlogger to her complaint about his reporting on the ‘Hampstead Hoax’ case of P and Q (Children: Care Proceedings: Fact Finding) [2015] EWFC 26 (Fam) High Court Judgment Template where two children were physically abused by their mother’s boyfriend to make fantastical allegations that babies were being murdered and eaten by local parents and teachers in some sort of Satanic abuse ring.

Campbell makes no mention of this case in her book, possibly because it is such a clear example of how children can be induced to say things that are not true and that goes against her hypothesis that such an assertion is a myth or a fable. Of course the P and Q case is a very extreme example. Most children are not tortured into making fantastic and false allegations. Most cases will be far more mundane and messy that this. I accept that children often find it very difficult to talk about being sexually abused, and for young children it is particularly difficult. But that is not a reason to assume that sexual abuse must be happening and to subject a child to repeated interviews, to say what the interviewer wants to hear. This kind of practice was rightly criticised in the Cleveland inquiry and again in the Orkneys investigations that followed.

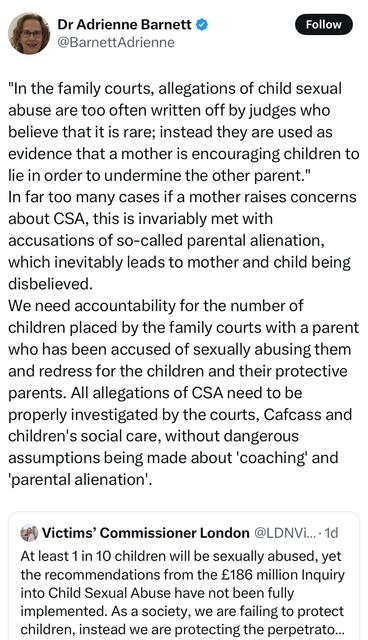

Far from Cleveland acting as a deterrent to accepting sexual abuse, it is clear that a strong lobby group has been established over the last few decades which asserts that sexual abuse is rife and that the family courts routinely fail female victims, particularly blaming mothers who raise allegations against fathers as practicing ‘parental alienation’. Social workers still appear to be trained to ‘believe’ the child and it has proved impossible to dislodge the word ‘disclosure’ from professional reports. For example, in one case I cross examined a social worker who had questioned 2 children about the same event and got 2 very different answers. Which child did she believe? Silence.

We know that when bizarre comments or compromised interviews are then filtered through a parent or professional who is keen to prioritise one narrative over another, the consequences for a fair hearing and hence uncovering anything like the truth, are obvious and severe. The Henriques report into Operation Midland and the fantasies of Carl Beech, demonstrated the catastrophe that can follow when fantasy is accepted at the outset without any kind of sceptical curiosity.

Conclusions

I understood the key finding of the Cleveland Inquiry to be not that the doctors or social workers were stupid and that children are liars, but rather that abuse is NOT a single agency or individual determination. That is as true now as it ever was. Doctors cannot ‘diagnose’ sexual abuse, it is not an illness. Rather they report and interpret clinical signs and give clinical opinions. Signs may ‘indicate’ or ‘suggest’ but can rarely provide a definitive answer alone. ‘Normal’ is the expected finding on examination in cases of abuse and non abuse, as normal examination is found in the majority of child sex abuse cases, even where the perpetrator has confessed. Multi agency working is essential and after Cleveland most suspected abuse cases were referred to community paediatricians in multi disciplinary teams. ‘

Campbell asked Bulter Sloss, 30 years on – what did she think professionals should do about the crux of Cleveland’s crisis: strong physical signs but little or no narrative? ‘She was candid: ‘I don’t know’. As with so much in the family justice system, we are faced with the ‘least worst option’. The family justice system puts proof of facts at it heart. We avoid the use of the word ‘disclosure’ as it means the ‘secret fact made known’. We refer to allegations because it is not the job of the lawyers, police or social workers to declare the ‘truth’ – that can only be the job of the criminal or family court.

As lawyers we owe first allegiance to the forensic process. We are not counsellors, psychologists or support workers. We work on the basis of what we can and cannot prove. And the key lessons from Cleveland remain important, most fundamentally that children are not just objects of concern but actual people who deserve protection and explanation. I appreciate that this call for recognition of children as human rings hollow in the light of what Campbell has uncovered about the financial motivations to cover up widespread abuse. That is a shameful failure. But I do not accept it is proof of continuing deliberate policy to deny the existence of sexual abuse of children. If anything, my professional practice causes me great concern that many would like to jettison any kind of forensic process entirely the moment an allegation of sexual abuse is raised.

Campbell argues that the medical scrutiny of children’s bodies is never neutral, it is always political. I agree with that up to a point. It is clear to me that issues of violence and abuse in the family justice system are often filtered through a particular ideological lens; either the family justice system is a tool of misogynistic oppression or it is rabidly anti fathers. A plague on both their houses. All I can do is stand firm in support of the rule of law, due process and evidence. Campbell states that this position is indicative of ‘hauteur’ or even ‘contempt’ as I present myself among the ‘objective, disinterested observers of other professionals causing havoc…’ I don’t accept that observation. Any one who begins an investigative process laden with any kind of ideological baggage or from any other starting point than ‘listen and take seriously’, risks corruption, failure and children left unprotected or further traumatised by inept procedures.

But I do accept to do justice to those principles of law, we need a child protection system that is fit for purpose. And that comes back round again to money. That the Cleveland Inquiry was used to promote a false narrative about the prevalence of child sexual abuse is shocking and I am grateful to Campbell for bringing that message very firmly home and correcting my false beliefs.

But the love of and the necessity of money cuts both ways. Many have built professional reputations and livelihoods on their ideological commitment to particular causes and effects of abuse and the funding they can attract. I note that shortly after the McMartin investigations began in the US, the budget of the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect (NCCAN) increased from $1.8 million to $7.2 million between 1983 and 1984, increasing to $15 million in 1985. Only $5 million was directed towards physical abuse and neglect.

It is neither ‘hauteur’ nor ‘contempt’ to demand fair and rigorous investigation into child abuse and to counsel caution against those with an ideological drum to beat. It is essential. And I don’t think it’s the legacy of the Cleveland Inquiry which is the biggest – or even any – part of the problems we face today. Failure to investigate issues of child abuse properly or at all is not explained, in my view, by some sort of ideological denial cemented by the Cleveland Inquiry, but rather the far less sexy but even more dangerous lack of resources, overwhelming case loads, the sheer scale of child poverty and the lack of effective early intervention for families.

Campbell, B Secrets and Silence: Uncovering the Legacy of the Cleveland Child Sexual Abuse Case

Further reading

Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel Nov 2024 The Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel – I wanted them all to notice

Explores the specific challenges which feature in the identification, assessment, and response to child sexual abuse within the family environment.

“The report reveals that safeguarding agencies were not equipped with the skills and support to listen, hear and protect these children from horrific abuse. It recommends the government urgently puts in place a national action plan to protect and support children at risk

The Independent Review looked at 136 child safeguarding incidents – the most serious cases of abuse and neglect – and found over 75% of the children sexually abused by a family member were under the age of 12.

The report reveals a system in which children are all too often ignored or disbelieved, do not receive the protection they need and in which the risk posed by adults within the family is frequently misunderstood or minimised. Importantly practitioners from all agencies lack the support, confidence and guidance required to intervene effectively to help and protect children.

Over a third of incidents featured a family member with a known history of sexual offending or who was known to present some risk of sexual harm. This included convicted sex offenders and family members who had been previously prosecuted for sexual abuse, including rape, moving into a home with young children without a strong risk assessment.

In order to combat this, the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel is urging the government to develop a national action plan which should include:

-

- Reviewing and updating initial training, early career and ongoing professional development and supervision, so that practitioners can fulfil their roles and responsibilities in identifying and responding to child sexual abuse.

- Ensuring that criminal justice and safeguarding agencies work together so there is robust assessment and management of people who present a risk of sexual harm and who have contact with children.

- Implementing a national pathway which provides a clear process to support practitioners from when concerns are first identified through to investigation, assessment and the provision of help.

- Instructing inspectorates to undertake a “Joint Targeted Area Inspection” focussing on multi-agency responses to child sexual abuse in the family environment.

Thousands more children’s social workers needed over next 10 years – new LGA research | Local Government Association Press release Nov 2024