This is a post by Sarah Phillimore. Helen Oakwater is an international trainer, coach and author. Her ‘world axis tilted’ in the early 1990s when she adopted a sibling group of children, then aged 5,4, and 2 from the UK care system. I am grateful for a chance to read and review her latest book prior to its publication. My own views about ‘forced adoption’ can be found in this post.

In March 2012 I reviewed Helen’s first book: ‘Bubble Wrapped Children – how social networking is changing the face of 21st century adoption’ . I commented then that I thought it did the book a disservice by apparently focusing on only one element of what was making closed adoption a trickier concept as electronic communications networks grow at exponential rate. In 2012 I said this:

The book inevitably has to cover a very wide range of topics in order to allow the reader to fully understand the full potential for harm from such unexpected contact to children already traumatised by earlier life experiences. The author sets out to explain the likely nature and extent of trauma suffered by the adopted child and the ways in which the child can be helped to make sense of his or her world. She also puts herself in the shoes of the birth parents and considers how they might be thinking and feeling and how this can influence their actions.

The book is thus an excellent resource for those coming new to the system and who require an introduction to the psychological theories around attachment and trauma. The author is able to present a number of quite complicated concepts in direct and vivid language, making good use of metaphor and diagrams to aid understanding; I found illuminating the example of child development as a river. Some rivers flow smoothly to the sea, others are turbulent with additional murky tributaries. Which river would you rather navigate?

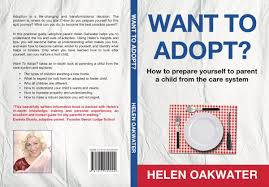

For me, the key issue then (and now) was Helen’s clear analysis of the difficulties ahead for children and their families given the almost inevitability that any adopted child will have suffered some kind of trauma and loss before joining their ‘forever’ family. Her second book takes this head on. It is called ‘Want to Adopt? How to prepare yourself to parent a child from the care system’. It will be published this spring.

The book is divided into three parts. Part 1 ‘I want my own healthy baby’ – immediately, in my view a sensible recognition of what often provides the dangerous tension in debates about adoption; providing children for those who cannot have their own biological children is a very different system from that which seeks out quasi professional parents to provide reparative care for some very traumatised children. The public face of the debate often seems to slide over this very necessary distinction and offers instead just platitudinous mantras about a ‘loving warm home’ being all you need.

Part two deals with ‘Stepping Stones’ – how to approach and deal with the necessarily intrusive assessment process that will follow into your capabilities and your motivations behind adopting. Because of the impoverished public discussion we generally have about adoption I would be very interested to know what the rates are of parents who apply to adopt and then drop out mid way or after the assessment process. Helen identifies the very pertinent and I think over over looked point that it isn’t just enough to prepare yourself for adoption – you must also prepare those around you who may make up your support team. They will also need to make efforts to understand the challenges and complexities of parenting a child with trauma.

Part three is ‘to cross the river or not’, looking at when hope and reality collide. Chapter 13 has some useful direct quotations from various adoptive parents. Helen focuses the discussion on the inevitability of disappointment and challenge in life and the need for an honest appraisal of how we propose to deal with this.

This is a useful and ambitious work which again presents some complicated concepts in clear and vivid language. I do find the use of quotes and diagrams useful, this is an engaging and interesting subject and it deserves a similarly engaging and interesting analysis.

As Helen says in her introduction:

‘This is one of the books I wish I had read before starting my own adoption process back in the early 1990s. I wish I had had this information throughout my journey. I wish I understood the impact of trauma in my own life and its devastating effect on the three children I adopted’.

She does not regret her decision or her children. But it is obvious that any such challenging life event is made easier to navigate with the right information, the right tools, the right people to help and guide you. My very real fear is that for far too long the debate about adoption has simply fallen between the ever widening abyss between the two polarised extremes: that children must be ‘rescued’ urgently from feckless parents where a warm and loving home awaits that will ‘fix’ them OR that any attempt to intervene to provide children with a safe and secure home is part of some murky conspiracy to line the pockets of individuals or agencies.

We need voices like Helen’s who are prepared to tell it like it is and break down this rigid and arid binary. The sentence that really jumped out at me was ‘when hope and reality collide’. So much of human misery that I see appears to stem from the often sadly vast gulf between what we know to be true and what we would like to be true. It takes a lot of energy to keep such dissonance alive. And its wasted energy. As Maslow says, the facts ARE always friendly. There is nothing dangerous or unsatisfying about being closer to the truth. The ‘truth’ about adoption may in reality be very far removed from the sanitised fairy tale of a ‘forever family’ but it is no less an extra-ordinary journey and for some children it is absolutely what they need.

I therefore hope Helen and others like her continue to speak and write and push for wider understanding of some of these fundamental issues. The better prepared adopted parents are, the more cognisant they are of the likely reality, the more able they will be to survive their journey which will be of immense benefit to them – and their children.

Of course, knowledge and preparation alone cannot magically solve all the problems – some of which are very serious and lead to the de facto breakdown of families. See the website of Parents of Adopted and Traumatised Teens for further discussion. Some adopted children will need considerable support beyond their immediate family and I have serious doubts about the availability and coherence of such support – but that’s a topic for another post!