This is a post by Sarah Phillimore. I look at the implications of the determination on the facts in the medical disciplinary proceedings bought against Dr Helen Webberley and consider the implications for professionals with statutory obligations to safeguard children. I hope the social work members of EBSWA will respond to this post and offer their insight into how social workers should respond, and hopefully we can organise a webinar to share our joint thoughts.

DETERMINATION ON THE FACTS – 22/04/2022

Dr Webberley has been a long standing and enthusiastic proponent of medical transition for children, and has prescribed female children under the age of 16 with testosterone via a variety of online services such as ‘Gender GP’. On 5 October 2018 she was convicted of two counts in relation to the carrying on or managing of an independent medical agency without being registered under the Care Standards Act 2000, and was fined £12,000. The General Medical Council challenged her continuing fitness to practice around allegations from her care and treatment of ‘transgender children’ in 2016/7.

The Tribunal found Dr Webberley competent to provide hormones to children, but she kept inadequate records, had failed to record or properly consider consent or provide adequate follow up care, leaving one child in a ‘state of anguish’.

The Tribunal will meet again in June 2022 to decide what penalty should follow these findings. I set out a precis of the background and the Tribunal’s reasoning below; for the full discussion please refer to the determination on the facts.

This determination has caused me significant concern. It makes four particular assertions which I do not think are supported by the available evidence and which have potentially harmful ramifications for children.

- ‘gender dysphoria’ is a product of something innate and physical. It is therefore wrong to label it a ‘mental illness’ and wrong to insist on ‘gate keeping’ via mental health screening. ‘Transgenderism’ has been ‘reclassified’ as a physical condition related to sexual health.

- Gender dysphoria manifesting before puberty is often self-remitting, whereas gender dysphoria persisting into puberty or manifesting itself during puberty is far more likely to require gender-affirming therapy.

- Those who object to the medical transition of young children are ‘unenlightened’ and their objections akin to homophobia.

- The Tribunal rejected the assertion that a child’s gender identity develops over time as ‘unevidenced’ despite the research over many decades of expert child development psychologists which supports this.

The Tribunal recognised that while hormones had been prescribed for transgender patients over many years, what was different now is the age of transgender patients to whom these hormones were being administered. However, it appeared to ignore or skate over the following issues:

- As the Divisional Court commented in Bell v Tavistock, there was a risk that the affirmation path ‘locked in’ children to escalating medical and surgical interventions

- The risk of social contagion, seen in the incredible surge in adolescent female patients at the Tavistock around the relevant time, many of whom were also diagnosed with autism

- The increasing narratives of those now in their early 20s who ‘destransitioned’ and feel profound regret

- The apparent internalised homophobia which appears to be motivating some parents

- The interim report of the Cass Review, that sets out the lack of any clear evidence base to support the assertion that puberty blockers and cross sex hormones are ‘harmless’ or ‘reversible’

- Reliance on assertion that children deprived of treatment may kill themselves; it is not clear from the determination what is the evidence base for this assertion.

Given that it the Tribunal did not restrict itself to simply making comment on the state of play in 2016/7 but were clear to criticise people as bigots if they didn’t support medical transition, in my view it was incumbent on them to at least consider the wider landscape and the rejection by the Cass Review interim report of their assertions that it is possible on the current state of the evidence to opine about the safety of prescribing testosterone to 11 year old girls. This report was in February 2022 so was available to the Tribunal prior to the handing down of their determination.

I am particularly concerned by the apparent lip service paid by the Tribunal to the fundamental importance of informed consent from children who are contemplating irreversible and life long medical or surgical intervention. This for example was Patient C’s level of thinking

I would like to not have boobs;

I’d like my boobs cut off – they wobble now and get on my nerves;

I want to have hormone blockers to stop my boobs growing because they are getting too big now. I know the boobs won’t go away;

Patient A was dismissive of the importance of any other intervention – note an email from patient A to Dr Webberley I find going to the Tavistock pointless, because James askes non related and personal questions for an hour, and not only is it boring, it doesn’t help me at all. I know we had to do it to get blockers, because we didn’t know about you at the time but I don’t want to go back as it is a waste of time

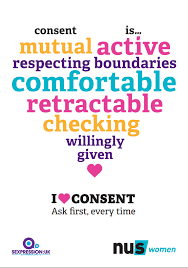

However the Tribunal did find that Dr Webberley failed to properly deal with issues around fertility with regard to Patient C – given that this child was aged 11 at the time, its very difficult for me to understand how informed consent to possible sterilisation could ever be given.

I think the implications of this for those professionals who work directly with children and have statutory obligations to secure their welfare – such as social workers – are very serious. I am not competent to unpick the medical evidence which informed the Tribunal’s determination but it is clear that the views asserted as ‘fact’ are, to say the least, controversial. Even if what they find is true – that ‘gender identity’ is something innate and identifiable in the physical structures of the body – what is the prevalence of such a condition? How is it identified? We appear to have no reliable way of identifying which children are genuinely gender dysphoric and which children have been told that ‘changing sex’ is the answer to the confusion they feel about possibly a multiplicity of other traumas or challenges in their lives.

To the man with a hammer, everything is a nail. I am worried that what is happening is that ideology is becoming baked into medical practice – as per Mermaids promotion that ‘a child of any age who says they are trans, are trans’. It is no reassurance that Dr Webberley’s bespoke ‘multi disciplinary team’ compromised of Dr Pasterski and her husband; both having demonstrating very clear allegiance to an ideology of gender identity expression. Dr Webberley has clearly worked closely with Mermaids and the emotional responses she gives in emails to the parents of her child patients sounds an alarm bell to the extent to which her professional clinical judgment is overshadowed by ideological zeal. Providing cross sex hormones to children is not a ‘civil rights issue’ – as Mermaids would have it. It’s a profoundly serious intervention in a child’s life with potential irreversible consequences and requires objective clinical assessment.

What appears to be motivating the ever decreasing age at which cross sex hormones are prescribed is concern by adults that the child will ‘not pass’ if allowed to go through puberty and develop secondary sex characteristics. But of course the alternative, as we see in the desperately sad case of Jazz Jennings, early administration of puberty blockers and cross sex hormones left the child with insufficient penile tissue to perform a successful penile inversion and construct a neo vagina – colon tissue had to be used.

This determination, if relied upon by professionals or parents as authoritative comment, puts social workers and lawyers in a very difficult position if they are attempting to advocate for ‘gender diverse’ children, effectively condemning them as ‘bigots’ if they express any concern about what is motivating a young child’s wish to medically transition. It is a very stark indication of just how urgently we need clear and definitive guidance. I have no doubt that ‘transition’ is being promoted to some very vulnerable and unhappy children as the ‘fix’ for all their problems. They are highly unlikely to be capable of understanding the ramifications of medical transition and its life long consequences. It is not ‘enlightened’ to subject children to a treatment they cannot understand and most will never need. To say that the view I express here is akin to ‘homophobia’ is insulting and ridiculous. I reject it. No gay child ever needed to deny their own physical body to be gay. When it comes to medicating children, I assert there are zero useful comparisons between ‘transgenderism’ – a belief in a ‘gender identity’ and homosexuality – a same sex attraction.

Suggested way forward

I offer the following guidance to lawyers and social workers who may now understandably be reeling in confusion from the starkly contradictory messages from this increasingly polarised issue. This is how I will approach such cases, on the basis of the knowledge and understanding I now have. I hope that social work members of EBSWA will now respond to this post with their suggestions for how we should approach the issue of ‘transgenderism’ in children under 16.

- Pre school children should not be encouraged to socially transition. There is no need for rigid gender stereotyping to be promoted at this age. Children ought to be allowed to wear what they like within reason and play with whatever toys they like

- If primary school children are expressing a wish to transition, then careful and holistic examination of their environment is required. What are the views of the parents? What other mental health/social challenges is the child facing? How do they impact upon issues of gender dysphoria? In my view it is highly unlikely that any primary school child would be Gillick competent to consent to even social transition and the child’s parents must be involved in any such decisions.

- Secondary school children are likely to be Gillick competent in many areas. However, the ramifications of medical and surgical transition are so serious I think it is likely the majority of children under 16 simply cannot given informed consent. The same careful analysis of their social environments is required. What support is available for them in terms of talking therapies? The issue of parental involvement is more complex if a Gillick competent child objects, but I suggest that schools should be slow to exclude a parent from information about a child’s claimed gender identity expression.

- Experts with an ideological bent or an overly emotional response to the issue of childhood medical transition should be avoided.

- Parents who claim that children have expressed ‘revulsion’ for their birth sex from a very early age should be treated with caution and their assertions not simply taken at face value.

Given the current state of the evidence and the worrying indications that many practitioners in this field are driven by ideological commitment to ‘gender identity expression’ I would favour a hard ban on any medical intervention for children under 14 and on any surgical intervention for any child under 18. I would prefer it if there was a professional obligation on doctors for a genuinely ‘multi disciplinary’ team to review any decision for cross sex hormones for a child under 16.

I call for continued rational and responsible discussion about what evidence we need to justify another approach and I hope the final Cass Report will assist us here. It is very difficult for me to reconcile the comments made by this Tribunal and the interim Cass Report.

Background

The allegations against Dr Webberley were extensive but can be briefly summarised; between March 2016 and May 2017, she failed to provide good clinical care and treatment to three transgender adolescents, appeared to be ignorant of safeguarding policy and had been dishonest about a variety of matters. The full details of the allegations are set out in the determination on the facts. The patients were aged 11 years and 10 months, 16 years and 3 months and 10 years and 7 months respectively, when they and/or their parent first contacted Dr Webberley.

The GMC case against Dr Webberley was essentially:

“…the care of transgender adolescents is complex and that, in consequence, the care of Patients A, B and C could only be delivered within a multidisciplinary team with input from specialists, particularly those from the disciplines of psychology/psychiatry and paediatric endocrinology. The GMC alleged that Dr Webberley, a GP, was not competent to deliver the care in question and that it was not delivered within a multidisciplinary team setting.”

Dr Webberley’s barrister made closing submissions in the following vein

‘This is the oddest of cases. No one has suggested that each of the patients did not suffer from gender dysphoria. No one has suggested that the treatment for gender dysphoria in this case is not puberty blockers and/or testosterone. None of the patients has complained about the care they received from Dr Webberley. Quite the contrary, the mother of Patient A and the mother of patient C were asked to provide statements to the GMC and the GMC obtained statements from them. Each is glowing in their support of Dr Webberley and each views the care that she provided to their son as life-saving.’

Patient A wished to transition from female to male; concerns were raised about the care and treatment provided by Dr Webberly in 2016 by Professor Peter Hindmarsh, the Clinical Director of Paediatrics at the University College London Hospitals. Patient A’s family had contacted Dr Webberley via one of her websites, and she prescribed ‘gender-affirmation hormone (‘GAH’) therapy – i.e. testosterone. Professor Hindmarsh was concerned this was not appropriate for a child under 16, the dose prescribed was too high and no attempts were made for patient A to undergo any psychological assessment or be manged by a multi disciplinary team (MDT).

Concern was raised over Patient B by Dr Roger Walters, consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist with the Buxton Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS). Patient B was a female who identified as male and was also receiving testosterone from Dr Webberley, which had been obtained by her internet website. Dr Walters was worried about the impact on Bs mental health and if this prescribing of testosterone was in line with standard practice. He attempted to liaise with B’s GP and Dr Webberley, who did not engage.

Patient C, another female wishing to transition to male, came to Dr Webberley aged 11 due to the long waiting lists for treatment at GIDs. Dr Webberley wrote to C’s GP, explaining that she wished to prescribe puberty blockers for C, having assessed C alongside a psychologist and explained possible issues re fertility. The GP surgery eventually sought advice from Professor Gary Butler at the UCLH, who raised concern that Patient C had been prescribed puberty blockers without the appropriate assessments, including any psychological assessments. Further, Professor Butler was also concerned that Dr Webberley’s clinical practice was restricted by the GMC, and that he had reported his concerns to the GMC.

The Tribunal received evidence on behalf of the GMC from a wide variety of witnesses, and on behalf of Dr Webberley from the following expert witnesses

- Dr Valerie Pasterski, Chartered Psychologist and Gender Specialist, report dated 19 August 2021;

- Dr Daniel Shumer, Paediatric Endocrinologist, reports dated 22 August 2021 and 25 August 2021

- Dr Walter Bouman, Consultant in Transgender Health, reports dated 23 August 2021 and 5 September 2021.

Its worth noting that Dr Pasterski was the expert who persuaded Mr Justice Williams to the ‘enlightened’ thinking that there was nothing remotely odd in two unrelated foster children aged 4 and 7, in the same family, expressing a wish to transition.

The GMC case relied on two clinical practice guidelines, namely 7th edition of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s Standards of Care (2012) (WPATHSOC7) and the Endocrine Society’s Clinical Practice Guidelines (2009) as benchmarks in transgender healthcare at the material time. The Tribunal agreed that WPATHSOC7 has the status of peer-reviewed expert guidance and that ‘transgender healthcare’ was an evolving discipline during the material time.

Transgender healthcare services for children and adolescents should, according to WPATHSOC7, be provided by a multidisciplinary team that includes, inter alia, mental health professionals and paediatric endocrinologists. Mental health professionals are central to the WPATHSOC7 vision of how transgender healthcare services should operate, the Tribunal noting the importance of mental health screening:

Clients presenting with gender dysphoria may struggle with a range of mental health concerns whether related or unrelated to what is often a long history of gender dysphoria and/or chronic minority stress. Possible concerns include anxiety, depression, self-harm, a history of abuse and neglect, compulsivity, substance abuse, sexual concerns, personality disorders, eating disorders, psychotic disorders, and autistic spectrum disorders. Mental health professionals should screen for these and other mental health concerns and incorporate the identified concerns into the overall treatment plan.’

The Endocrine Society Guidelines 2009 endorsed the then prevailing WPATH guidelines (WPATH-SOC6) regarding the gate-keeper role of the mental health professional but, surprisingly for a document written by endocrinologists, it contained no guidance concerning the training or competencies required of a hormone-prescribing physician. The Tribunal found it difficult to reconcile the roles of hormone prescriber and diagnostician if the former is an endocrinologist and the diagnosis is a mental illness.

The Guidelines suggest that to receive ‘gender-affirming hormones’ an adolescent should be over 16 but this was a ‘suggestion’ not a ‘recommendation’. The Tribunal found this suggestion was based on the legal position that children aged 16 are generally considered as adults for medical decision making; it did not have a medical or biomedical basis.

Both WPATHSOC7 and Endocrine Society Guidelines 2009 advocate a staged approach to physical interventions in transgender healthcare. Stage-1 involves the arresting of endogenous puberty through the administration of medications such as GnRHa. Stage-2, the administration of gender-affirming hormones to induce transgender puberty. Stage-3 is the surgical remodelling of the body. Stage-1 interventions are regarded as fully reversible, although concerns have been raised that protracted use of GnRHa may impact adversely on skeletal health; stage-2 as partially reversible and stage-3 as irreversible.

The Tribunal noted that there were no NICE guidelines specifically relating to the treatment of gender dysphoria at the material time, nor have any been developed to date and therefore while GIDS is contractually obliged to deliver its service in line with emerging evidence for best practice, it is in reality tethered to WPATHSOC7 and Endocrine Society Guidelines 2009.

To access endocrine interventions, GIDS service users must undergo multiple stepwise or concomitant assessments by multiple mental health professionals over a period of many months to establish a psychiatric diagnosis of gender dysphoria and to confirm persistence of gender dysphoria. This is based in part on evidence that gender dysphoria in pre-pubertal children is often self-remitting. However, the Tribunal found it was crucial to distinguish between children and adolescents, relying on guidance in WPATHSOC7 and concluded: Gender dysphoria manifesting before puberty (i.e. in children) is often self-remitting, whereas gender dysphoria persisting into puberty or manifesting itself during puberty is far more likely to require gender-affirming therapy.

The Tribunal referred to Bell v Tavistock [2020] EWHC 3274 (Admin) but made no mention of the concerns expressed by the Divisional Court that the ‘affirmation’ path of puberty blockers followed by cross sex hormones may be a difficult one for a child to leave. Instead the Tribunal concluded that :

In summary, adolescents that consent to puberty blockers do not need ‘time to think about their gender identity’: they are already settled in their mind and almost invariably seek gender-affirming (stage-2) hormone therapy.

On this rather unusual understanding of adolescent decision making prowress, it is not hard to see why the Tribunal were then critical of GIDs, having

“an unyielding protocol-driven approach to its psychological assessment phase. Far from being tailored to the needs of individual service users, it evidently imposes a one-size-fits-all diagnostic/assessment protocol. Access to hormone therapy via GIDS is, moreover, dependent upon service users meeting DSM-5 criteria for gender dysphoria and thereby accepting that they have a mental illness.

The Tribunal found this particularly pertinent when considering the ‘evidence’ at the material time that gender dysphoria is not, in fact, a mental illness and concluded that opinion was and still is divided amongst experts as to the optimal approach.

The Tribunal found that a shift in terminology to ‘gender incongruence’ reflects a fundamental shift in medical and societal attitudes to transgenderism and gender dysphoria is no longer to be regarded as a mental illness but rather a physical state of being, not a state of mind. This is based on ‘evidence’ that gender identity is innate, rather than learned. This evidence includes ‘post-mortem evidence that the structural neurobiology of the brain is involved in the establishment of gender identity.’

The Tribunal called this ‘enlightened thinking’ and rejected the Endocrine Society guidelines which states that one’s self awareness as male or female evolves gradually during infant life and childhood’.

The most astonishing assertion of the Tribunal is at para 111

The Tribunal finds that the reluctance of the Endocrine Society and others to embrace enlightened views of transgenderism is symptomatic of the tendency in all professions to be slow to move with the times. This inertia in respect to medical attitudes to transgenderism mirrors past attitudes to homosexuality, which was classified by the APA as a mental illness until the 1973 edition of their DMS.

The Tribnal asserted that the ‘de-psychopathologisation’ of gender dysphoria and view in 2016/17 that transgenderism was no longer to be regarded as mental illness, was highly relevant.

The reclassification of transgenderism as a somatic state related to sexual health, as opposed to a mental illness, had clear implications for the competencies necessary to deliver safe and effective care to those presenting with gender dysphoria.

The Tribunal therefore supported Dr Webberley’s case that, as an experienced GP and a doctor with a longstanding professional interest in sexual health, in the healthcare needs of minorities, such as gender-variant persons, and in the administration of hormone therapies, she was competent to provide safe and effective care to Patients A, B and C. The Tribunal found that Dr Webberley was hampered by the lack of formal training opportunities in transgender health at the material time and that her lack of validated qualifications in transgender healthcare cannot, therefore, be held against her.

The Tribunal further found that that GPs are competent to recognise and treat, or refer onwards for specialist treatment, persons with mental ill health arising as a reaction to minority stress. Dr Webberley, as an experienced GP and as a doctor with a special interest in transgender healthcare, was most certainly competent in those respects.

The Tribunal did note that ASD is overrepresented in the gender dysphoric population. For example, WPATHSOC7 states that ‘The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders seems to be higher in clinically referred, gender dysphoric children than in the general population.’ Published estimates of the prevalence of ASD in those referred to gender identity clinics vary from 9% to 26% and that valid consent was a ‘profoundly important issue in transgender health care’ given the potentially irreversible effects of gender-affirming hormones. Hormone ‘therapy’ was already a long established treatment in transgender healthcare – what was different now however was the much younger ages at which such intervention was sought.

The Tribunal concluded that it was safe to give testosterone to girls under 16 – or at least there was no evidence to say it was unsafe. It relied in part on a study that included a mere thirteen patients below the age of sixteen and reported no adverse outcomes. This has led to a ‘stage-not-age’ view of when administration of sex steroids is clinically indicated: some experts, such as Dr Shumer, now deem that it is the pubertal stage of the patient that matters, not their chronological age.

The Tribunal then considered if Dr Webberley was competent to prescribe hormones. It found Dr Webberley an ‘impressive witness’ with a ‘depth and breadth’ of knowledge of endocrinology and hormone therapies and she was competent.

The Tribunal stressed that a wish to reduce waiting times or ‘give in to insistent demands from patients for immediate treatment’ can never allow a doctor to compromise patient safety and care – but when an established facility is unable to cope with the demand for its services, it is incumbent on other practitioners in the sector to seek out alternative ways to help those patients in pressing need of attention but facing inordinately long waiting lists. That some patients with gender dysphoria are so desperate they are driven to suicide gives considerable impetus to this need for alternative approaches. No evidence is given to support this suggestion that depriving hormones will lead to suicide.

The Tribunal found that in 2016/7 there was immense pressure on GIDS and that some aspirant service users were, as a result, left in a state of desperation and the ‘rigid and protocol- driven approach’ at GIDs did not meet their needs.

The Tribunal found as a matter of fact Dr Webberley did adopt a multi disciplinary approach to her practice, by developing professional links with psychologists and counsellors and offered a ‘bespoke approach’ to her care of patients. The Tribunal went so far as to comment that Dr Webberley’s approach might be regarded as being at the vanguard of this evolving approach to transgender care. This is despite the various findings about Dr Webberley’s failure to provide adequate standards of care. She failed to provide adequate follow up care to patient A. There was no communication from Dr Webberley and A’s mother between July 2016 and February 2017. She had a duty to communicate with GIDs who were also treating A and she did not, knowing that if she did the Tavistock would withdraw treatment. She failed to ensure adequate records were kept, particularly about issues around consent. Her reliance on sending emails as a substitute for proper record keeping was ‘lazy’.

It is also deeply alarming to see reliance placed by the Tribunal on Dr Webberley’s ability to rely on her husband Dr Michael Webberley, described as ‘a general physician who had experience in endocrinology’. There is no reference to Dr M Webberley’s on going fitness to practice tribunal hearing which has seen highly critical evidence from a number of expert witnesses.

An email from A’s mother makes for particularly sad reading

‘Hi,

I attempted to contact you and Katie numerous times regarding the next prescription of testosterone, the blood tests that you stated were a necessity, and to let you know that without the authorisation of NHS professionals, my GP would not assist with this.

However, I received no response for two whole months. You claimed that they had not been received, and that I should instead send messages to your personal email address, but I had already done this, in addition to sending messages to the email address of the secretary. While one or two could perhaps have slipped through the net, it didn’t seem feasible that they all had gone wayward.

It was obviously hugely concerning that we had apparently been left devoid of guidance, advice, support, prescriptions or ability to get any tests performed, or even any correspondence. So, after the Tavistock had phoned me a few times, I had to admit that we had already been receiving treatment from elsewhere, though the details were not discussed. Dr Gary Butler, [Patient A’s] endocrinologist, personally rang me to ask what dosage of testosterone [Patient A] was receiving, and when I divulged the figure, he was exceptionally concerned, and dedared it was the dosage only an adult should take. He elucidated that a child of [Patient A’s} age should only be taking a small fraction of the dosage, which would allow him to progress through puberty at the same rate as his peers, and mentioned that the breaking of the voice should take a few years -which I recognised to be true from when my older son’s voice broke. The fact that [Patient A’s] broke within two weeks, including other developments, was alarming to say the least. This new information, coupled with the fact that we felt so abandoned, assisted with the decision to continue seeking assistance from the NHS, as at that particular juncture we felt we had no other option! It wasn’t until quite some time later that I received an email from you asking for an update, to which t responded, and then you replied that you hadn’t received any of my messages. So, basically we are now back in the hands of the NHS, and left to wait the painful three years until [Patient A] is 16! However, travelling abroad for treatment is still an option being considered, as [Patient A] doesn’t want to wait until then.

I wish you all the best, but do think that procedures should be thorough, and from what I have been told, you are not an endocrinologist, nor an expert with hormones, and that treating adults in this field Is fine, but treating children is a different kettle of fish entirely. This is obviously not from me – I just want what is best for my son, and feel like I’m in a horrendously tricky situation, and am rather depressed knowing that following the NHS guidelines will mean my son has to wait until he is 16, whereas other countries can prescribe from 14, and have prescribed, cross-sex hormones to children of 12 with great success!’

It is also extremely concerning to read about how A was now behaving, with episodes of violence and suffering chronic depression.

It is alarming to read that A’s mother believed her daughter to have been displaying repulsion at anything conveying their biological gender, going back to when they were just 9 months old (which is as early as they were able to display it) What exactly it was that this baby displayed which could be interpreted as such repulsion, is not explained but it raises interesting and worrying questions about the environment in which A was raised and the degree of parental influence on how ‘repulsion’ was perceived and interpreted

With regard to Patient B, Dr Webberley had not carried out sufficient assessment of her mental health state which meant she had not been able to properly consider if some of B’s disturbing behaviours required treatment for something other than gender dysphoria. With regard to Patient C, although Dr Webberley had sought assistance from Dr Pasterski, she had not considered when assessing C other possible alternative diagnoses that may provide an alternative explanation for the dysphoric feelings or complicate them.

So the determination gives some useful indication of where Dr Webberley fell short, which hopefully can be of assistance to other GPs. But its explicit assertions that medical transition of the under 16s is ‘safe’ and objections to it are some kind of bigotry should profoundly worry all of us charged with the protection of children.

Further reading

And an excellent point in this substack from Dave Hewitt which I missed – despite criticising Dr Webberley for not being sufficiently conscientious in recording the child’s consent, the Tribunal concluded at para 25 it didn’t matter because the parent could consent on their behalf. This in spite of the Tavistock confirming in Bell that they would never dream of treating a child who did not or could not consent.

Regarding consent, the tribunal – having previously decided that children’s self-knowledge is paramount – went on to declare that parents can consent for children who lack comprehension, so all questions as to Webberley having effectively established consent were moot. Not only that, if a child disagrees with the treatment, but is not Gillick competent, the parent can consent anyway: