Keira Bell’s case, which began on October 7th 2020 has provoked a lot of comment about the issues of children and their capacity to consent to medical treatment. This is an attempt to provide a quick over view in easy to understand language. If you are interested in this area in greater detail, I set out some ‘further reading’ at the end of this post.

Medical treatment is only lawful if given in an emergency or with informed consent.

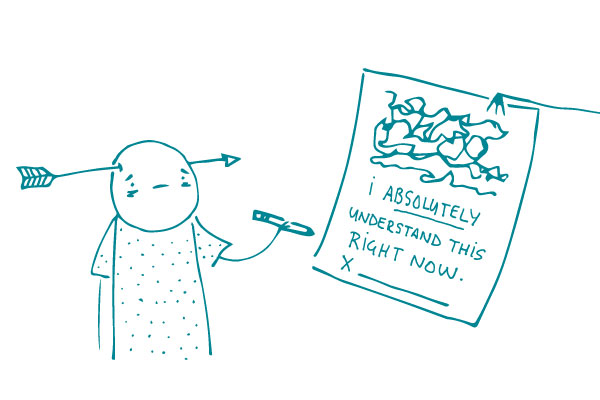

The case of Montgomery (Appellant) v Lanarkshire Health Board (Respondent) (Scotland) [2015] UKSC 11 deals with what risks about birth should have been shared with an adult patient – but is a useful discussion of the general parameters of what can be meant by ‘informed consent’ – patients do not have the medical knowledge of doctors, may not know what questions to ask. Doctors have a duty to reveal and discuss ‘material’ risks with a patient.

At para 77 the court comments approvingly on 2013 guidance to doctors:

Work in partnership with patients. Listen to, and respond to, their concerns and preferences. Give patients the information they want or need in a way they can understand. Respect patients’ right to reach decisions with you about their treatment and care.”

In a genuine emergency, doctors are unlikely to be penalised for treating a patient on the spot. In all other cases, medical intervention to which the patient does not consent is likely to be a crime.

Someone is said to lack capacity if they can’t make their own decisions because of some problem with the way their brain or mind is working. This could arise due to illness, disability or exposure to drugs/alcohol. It doesn’t have to be a permanent condition.

Some people lack capacity because their disability or injury brings them under the terms of the Mental Capacity Act and they cannot understand or weigh up the necessary information. These cases may have to go to the Court of Protection so the Judge can decide what is in their best interests.

Some people lack capacity because they are a child. A child is a person aged between 0-18. While most people would agree that a child aged 4 is unable to make any serious decisions on his own, the waters get muddier the older a child gets, as their understanding and desire for autonomy increases.

A child over 16, who doesn’t have any kind of brain injury or disability, is presumed to be able to consent to medical treatment as if an adult, under the Family Law Reform Act 1969.

Children under 16 may have capacity if they have enough understanding of the issues – this is called Gillick competence, from the case of the same name.

Adults who have parental responsibility for a child can give consent when a child cannot. However, the older the child gets, the more likely there is to be tension between what the adult and child think is best.

If the child, parents or doctors cannot agree about what treatment is best, then this has to come before the court to decide. A very sad example of this which got a lot of media attention, is the case of Alfie Evans, a toddler whose parents disagreed very strongly with the medical advice that his life should not be prolonged.

Applying the basic principles to the Bell case

I have seen some very odd comments about this case. However, first – if it is correct that Bell’s lawyers are arguing that NO child ever could consent to taking puberty blockers, I agree this is a bold submission and would certainly seem to be moving away from the clear statutory recognition of the likely autonomy of the 16 year old child. It may be that this submission rests on the grave concerns about the experimental nature of such treatment – and certainly the Tavistock does not seem to be able to provide the court with much if any hard data about the longer term consequences of this.

But any suggestion that the Bell case will somehow ‘destroy’ Gillick competence and deny 15 year old girls the right to contraception or abortion, is simply wrong.

The first and basic point is that Gillick was decided by the House of Lords – now the Supreme Court. The High Court has no power to change or alter the decision of the Supreme Court. Second point is that even if Bell’s case does succeed in getting a declaration from the High Court that NO child can ever consent to taking puberty blockers for transition, this will not impact other areas of decision making for children about medical treatment.

This is because the nature and quality of such treatments is well known and researched. It is therefore possible to weigh up the consequences, benefits and risks, in a way many would argue is simply impossible for puberty blockers given to aid ‘transition’ rather than to deal with precocious puberty.

When the nature and quality of such treatments are not known and doctors are unhappy to offer it, or a child (or parents) is refusing consent to a treatment that the doctors say is essential, then the matter will need to come to court.

Conclusion

I await the judgment in Bell with very keen interest. It will certainly need to cover all the areas I briefly touch on above, and hopefully will make such vital issues much clearer for many.

I accept a small minority of children DO need access to puberty blockers to prevent the development of sex characteristics they find very distressing. But I think they will be a tiny minority. I think the evidence to dates shows very clearly the impact of some kind of social contagion around issues of ‘gender identity’ which has led to staggeringly high numbers of children seeking ‘transition’ as a cure all for their emotional distress.

While I do not agree that NO child is capable of consenting to take these drugs, I certainly agree that the evidence base which will inform them of the risks and benefits is lacking, and dangerously so.

EVERY child should be given the right information in order to make these decisions.

Further reading

How do children consent? The interplay between Gillick competence and Parental Responsibility CPR January 2020

A child’s consent to transition; the view from Down Under CPR September 2020

In whose best interests? Transitioning pre school children Transgender Trend October 2019

The Impossibility of Informed Consent for Transgender Interventions: The Risks Jane Robbins April 2020

Freedom to Think: the need for thorough assessment and treatment of gender dysphoric children Marcus Evans June 2020