This is a post by Sarah Phillimore

I am writing this post because I am concerned that there is a strong view in certain circles that ‘parental alienation’ either does not exist or is very rare and used as a deliberate strategy by violent men to deny contact with children to the mothers they oppress.

I don’t agree that parental alienation doesn’t exist. There is abundant evidence that it does. Nor do I agree that falsely asserting parental alienation as a strategy is commonplace, although I am sure it does happen.

Therefore I find it concerning to see the very existence or importance of parental alienation ‘downgraded’ by a number of academics and lawyers – particularly when those academics are involved in the recent MoJ report into private law cases. I have set out my criticisms of and concerns about this report here.

I endeavour always to render my criticisms reasonable, balanced and evidenced. So it was surprising and rather shocking to be called a ‘troll’ on social media and accused of ‘picking on’ victim of DV by one of the academics involved in a literature review for the MoJ.

This is not a helpful response from anyone. It is a particularly bizarre and inappropriate response from someone with a seat at the table of political influence.

This view about parental alienation as a ‘grand charade’ is set out here by Rachel Watson in July 2020. She says

A pattern emerged in the family courts (England & Wales) of parental alienation (PA) raised as a response to domestic abuse claims, as proved in Dr Adrienne Barnett’s research published in January 2020. It resulted in devastating outcomes for mothers and children. The need for a child to maintain contact became a priority as we were subtly influenced to believe in a new stereotype; a hostile, vindictive mother; a woman scorned, one who used her child as a pawn. Domestic abuse was reframed by controlling, abusive fathers who denied their behaviour, lied about it and projected it onto bewildered, abused mothers. Fathers’ rights groups powerfully marketed the new stereotype. They cried from the rooftops;

“Mothers lie about abuse and cut off contact from deserving fathers; we are the true victims; there is a bias against us!”

Judges routinely minimised domestic abuse in the courtroom; mothers were disbelieved, dismissed and punished through the contact arrangements. Welfare reports were often carried out by unsuitable and underqualified assessors.

I don’t agree with this. It does not reflect my own experience of 20 years in the family courts. That others seem to have a profoundly different experience is worrying. I would like to know what explains the gulf between my understanding and theirs. Given that this will be impossible to achieve in a blog post, I will restrict myself here to addressing the issue of parental alienation as a ‘grand charade’.

What do the courts say about parental alienation?

Let’s look at just two examples from published court judgments. There are sadly many, many more. I hope even this brief discussion makes it clear that ‘parental alienation’ is a phenomenon that exists and which does tremendous harm. Both the alienating parents in these cases were mothers; that does not mean that this is a sex dependent failure of parenting. Fathers can and do alienate their children from their mothers. It is wrong regardless of the sex of the parent who does it.

D (A child – parental alienation) (Rev 1) [2018] EWFC B64 (19 October 2018).

The child D was born in 2005. Proceedings had been ongoing for over ten years, albeit with a four year respite from 2012 – 2016, and had cost a staggering amount of money for both parents – about £320,000 over ten years.

There was a residence order made in the father’s favour in 2011 and the mother’s application to appeal was refused in 2012. Following a relatively peaceful four years, the mother then refused to return D to his father’s care in November 2016 and the father did not see D again until March 2017. A final hearing was listed for April 2018 after the instruction of a psychologist.

in early 2018 D made allegations of a serious assault upon him by the father and contact against ceased. The police became involved but took no further action and the Judge granted the father’s application in August 2018 that D give evidence at the finding of fact hearing.

D gave evidence and was very clear, saying (para 74):

I just want a normal life, living in happiness with mum. I cannot go back to my father’s. I was promised by my mum and the police officer that dad wouldn’t hurt me ever again. Now, I am here in court because he hurt me bad. Why can’t I just have a life that isn’t based on court and stress? I just want a life that I can live not live in fear from, please.’

D’s guardian put forward a schedule of six allegations that D made against his father. The court noted the evidence of the psychologist Dr Spooner at para 85.

D presented with what seemed like a pre-prepared and well-rehearsed script of all the things he wanted to tell me about his father. He took every opportunity to denigrate him, his family and his partner. Each time I attempted to ask him about issues not related to his father, such as school, hobbies and so on, he quickly derailed himself and continued on his frivolous campaign of denigration.

The court heard a great deal of evidence from social workers and other experts about the alleged injuries suffered by D. It is disturbing to note how the Judge was not assisted by some of the evidence from the local authority, not least because the social worker who prepared the section 37 report was working from the assumption that everything a child said must be true.

The father denied assaulting D but had to hold his arms when D was being aggressive towards him. The Judge did not find any of the allegations proved; he found the father and his partner to be honest witnesses and this was a case where the mother was determined to ‘win’ at any cost. The judge found that she had deliberately alienated D from his father.

Analysis of what is meant by ‘parental alienation’

From paragraph 165 the Judge considered the issue of parental alienation. At para 169 he refers to the research Dr Julie Doughty at Cardiff University. She comments:

There is a paucity of empirical research into parental alienation, and what exists is dominated by a few key authors. Hence, there is no definitive definition of parental alienation within the research literature. Generally, it has been accepted that parental alienation refers to the unwarranted rejection of the alienated parent by the child, whose alliance with the alienating parent is characterised by extreme negativity towards the alienated parent due to the deliberate or unintentional actions of the alienating parent so as to adversely affect the relationship with the alienated parent. Yet, determining unwarranted rejection is problematic due to its multiple determinants, including the behaviours and characteristics of the alienating parent, alienated parent and the child. This is compounded by the child’s age and developmental stage as well as their personality traits, and the extent to which the child internalises negative consequences of triangulation. This renders establishing the prevalence and long-term effects of parental alienation difficult…’

At para 170 the Judge considers the CAFCASS assessment framework for private law cases. The assessment contains a section headed ‘Resources for assessing child refusal/assistance’ which in turn has a link to a section headed, ‘ Typical behaviours exhibited where alienation may be a factor ’. These include:

- The child’s opinion of a parent is unjustifiably one sided, all good or all bad, idealises on parent and devalues the other.

- Vilification of rejected parent can amount to a campaign against them.

- Trivial, false, weak and/or irrational reasons to justify dislike or hatred.

- Reactions and perceptions are unjustified or disproportionate to parent’s behaviours.

- Talks openly and without prompting about the rejected parent’s perceived shortcomings.

- Revises history to eliminate or diminish the positive memories of the previously beneficial experiences with the rejected parent. May report events that they could not possibly remember.

- Extends dislike/hatred to extended family or rejected parent (rejection by association).

- No guilt or ambivalence regarding their attitudes towards the rejected parent.

- Speech about rejected parent appears scripted, it has an artificial quality, no conviction, uses adult language, has a rehearsed quality.

- Claims to be fearful but is aggressive, confrontational, even belligerent.

Re A (Children) (Parental alienation) [2019] EWFC

The Judge said this about the case

In a recent report to the court, one of this country’s leading consultant child and adolescent psychiatrists, Dr Mark Berelowitz, said this: ‘this is one of the most disconcerting situations that I have encountered in 30 years of doing such work.’ I have been involved in family law now for 40 years and my experience of this case is the same as that of Dr Berelowitz. It is a case in which a father leaves the proceedings with no contact with his children despite years of litigation, extensive professional input, the initiation of public law proceedings in a bid to support contact and many court orders. It is a case in which I described the father as being ‘smart, thoughtful, fluent in language and receptive to advice;’ he is an intelligent man who plainly loves his children. Although I have seen him deeply distressed in court because of things that have occurred, I have never seen him venting his frustrations. It is also a case in which the mother has deep and unresolved emotional needs, fixed ideas and a tendency to be compulsive.

The Judge felt it was important for this judgment to be published, albeit heavily anonymised to protect the identities of the children.

My intention in releasing this judgement for publication is not because I wish to pretend to be in a position to give any guidance or speak with any authority; that would be presumptuous, wrong and beyond my station. However, this is such an exceptional case that I think it is in the public interest for the wider community to see an example of how badly wrong things can go and how complex cases are where one parent (here the mother) alienates children from the other parent. It is also an example of how sensitive the issues are when an attempt is made to transfer the living arrangements of children from a residential parent (here, the mother) to the other parent (the father); the attempts to do so in this case failed badly.

The UK Parental Alienation Study

In 2020 Good Egg Safety CIC produced a report about parental alienation and its impact, concluding that parental alienation was:

A devastating form of ‘family violence’ with psychological abuse and coercive control at its heart

Of the 1, 513 who responded to the survey, parental alienation was a live issue for 79% of respondents who were split 56% male, 44% female. 80% experienced an adverse impact on their mental health, 55% an adverse financial impact. 58% saw court orders breached.

Conclusions

Of course, the same criticisms can be made about this survey as I made about the MoJ survey. We have to be careful about the results of a survey conducted with the self selecting. The MoJ reassured itself this was ok because the wide ranging review of case law and literature supported the view of the self selecting respondents that family courts routinely ignore issues of violence.

The problem however, as I pointed out above, is when you have someone conducting your literature review who thinks that those who talk about parental alienation as a real thing are ‘trolls’.

It is my view that the case law abundantly supports the findings of the Good Egg Safety report. Parental alienation exists and it does enormous harm to the children and parents caught up in it. It is not restricted to women as perpetrators – but I am sad to say that in all the cases of parental alienation in which I have been involved over 20 years, the majority of those found to be perpetrators by the court were women.

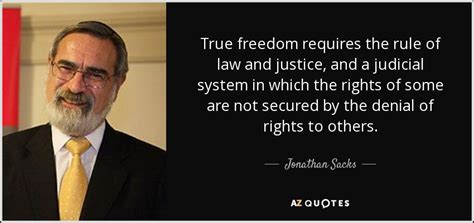

It also does enormous harm to the rule of law and respect for court orders. Pretending it doesn’t exist or that it exists primarily as a strategic tool for abusive men to further their abuse is plain wrong. I suspect those who promote this theory know on some level how wrong they are, given the level of abuse and insults they throw at anyone who challenges them.

You may not like what I say. You may – with some justification I concede – accuse me of rudeness or abruptness in the way I say it. But I am no troll. That is a baseless, insulting assertion and it will not help your arguments gain or sustain any credibility whatsoever.

For those now asking in despair – but what do we DO about all this? I set out some suggestions in this post. But as many of them will involve a significant financial investment in both judges and court buildings, I do not expect to see any change in my life time. But I will continue to do what I can to promote honesty and openness in the public debate about such important issues.

Further reading

Case Law

A case where shared residence was agreed after 10 year dispute – see Re J and K (Children: Private Law) [2014] EWHC 330 (Fam)

See Re C (A Child) [2018] EWHC 557 (Fam) – Unsuccessful appeal to the High Court by a mother against a decision which transferred the residence of C, aged six, to her father, in light of the mother’s opposition to progressing C’s contact with her father. Permission to appeal was refused as being totally without merit.

Transfer of residence of child from mother to father – RH (Parental Alienation) [2019] EWHC 2723 (Fam) (03 October 2019)

Re S (Parental Alienation: Cult) [2020] EWCA Civ 568 – child ordered to live with father if mother continued to refused to give up her adherence to a ‘harmful and sinister’ cult.

Re A and B (Parental Alienation: No 1) 25 Nov 2020 [2020] EWCH 3366 (Fam)

X, Y and Z (Children : Agreed Transfer of Residence) [2021] EWFC 18 (26 February 2021)

Articles and Research

What is the evidence base for orders about indirect contact?

See this article from the Custody Minefield about how intractable contact disputes can go wrong or get worse.

Address from the President of the Family Division to Families Need Fathers, June 2018

Review of the law and practice around ‘parental alienation’ in May 2018 from Cardiff University for Cafcass Cymru. There is a very useful summary of the relevant case law in Appendix A. The report concludes at para 4.7:

With no clear accepted definition or agreement on prevalence, it is not surprising that there is variability in the extent of knowledge and acceptance of parental alienation across the legal and mental health professions. The research has however, provided some general agreement in the behaviours and strategies employed in parental alienation. This has led to the emergence of several measures and tests for parental alienation, although more research is needed before reliability and validity can be assured. Many of the emerging interventions focus upon psycho-educational approaches working with children and estranged parents, but more robust evaluation is needed to determine their effectiveness.

The Cafcass Child Impact Assessment Framework (CIAF) sets out how children may experience parental separation and how this can be understood and acted on in Cafcass. The framework brings together existing guidance and tools, along with a small number of new tools, into four guides which Cafcass private lawpractitioners can use to assess different case factors, including:

- Domestic abuse where children have been harmed directly or indirectly, for example from the impact of coercive control.

- Conflict which is harmful to the child such as a long-running court case or mutual hostility between parents which can become intolerable for the child.

- Child refusal or resistance to spending time with one of their parents or carers which may be due to a range of justified reasons or could be an indicator of the harm caused when a child has been alienated by one parent against the other for no good reason.

- Other forms of harmful parenting due to factors like substance misuse or severe mental health difficulties.

Resources and Links recommended by the Alienation Experience Blog

Useful analysis of case law from UKAP.ONE

The Empathy Gap 14th June 2020 – Commentary on Adrienne Barnett in “A genealogy of hostility: parental alienation in England and Wales”, Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law (Jan 2020). The paper discusses the role of parental alienation within the English and Welsh family courts.

The Empathy Gap 11th June 2020 – Commentary on “U.S. child custody outcomes in cases involving parental alienation and abuse allegations: what do the data show?”, By Joan S. Meier, Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law 42:1, 92-105 (2020)