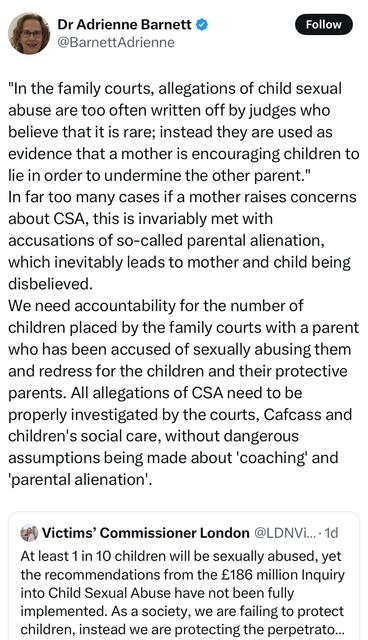

On 3rd June 2025 the High Court handed down judgment in the case of N v N (Expert Evidence on Gender Affirming Treatment) [2025] EWHC 1325 (Fam)

This case involved a child B who was 17 in May 2025. The court refers to the child as ‘she’ but it is clear that B is male so I will use male pronouns. His parents wanted a declaration that B lacked capacity to consent to taking cross sex hormones as ‘gender affirmation’ treatment. The child had a Guardian but instructed his own legal team. The father had also made an application for judicial review of the decision of B’s GP to prescribe hormones to children.

Sarah’s Newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.Subscribed

B lives with his parents and had been prescribed female hormones by a GP since October 2024 pending referral to a specialist gender service. B forged his mother’s signature to get this prescription. In March 2025 CAMHS confirmed that B had ‘gender incongruence’ and accompanying distress.

B’s parents were concerned that there had been no proper holistic assessment of his overall mental and physical health to inform such treatment and this was not in line with the Cass Review and other professional guidance.

This judgment followed a case management hearing, all parties agreeing it was necessary to instruct an expert endocrinologist to assist the court. However, they couldn’t agree that expert’s identity. The parents also wanted to instruct a psychiatrist to report on B’s capacity and asked the court to agree that this was a special ‘medical treatment’ case so each party should be allowed to instruct their own experts. The usual way forward in family cases is for a single joint expert.

B disagreed that a psychiatrist was necessary on the basis that there was no evidence he lacked capacity or that the current treatment risked serious harm to him. If the court didn’t accept B’s position, it should not endorse the parents’ chosen expert, as he sought to advance a particular view about ‘gender affirming’ treatment, i.e. he was not a fan. Equally, the parents’ chosen endocrinologist should not be appointed, as she too ‘has a fixed agenda to advance’ (para 11).

The relevant law

The court then examined the relevant law regarding children’s capacity and referred to the earlier Court of Appeal decision in O v P which I have written about here.

It is useful at the outset to distinguish between three possible issues with which the courts have to deal. First, there is the issue of whether a child under 16 is competent to consent or to refuse medical treatment (see Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech AHA [1986] AC 112 (Gillick), and more recently R(Bell) v Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust [2021] EWCA Civ 1363, [2022] 1 All ER 416 (Bell v Tavistock). Second, there is the issue of whether a child (but also an adult) has mental capacity to consent to or to refuse medical treatment (see sections 1-6 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005). Thirdly, there is the issue of what is in the child’s best interests. This issue arises once the presumption as to competence of a child over 16 to consent or refuse medical treatment is engaged (see section 8 of the Family Law Reform Act 1969 (FLRA 1969), which provides that a child over 16 can give consent in the same way as an adult, and not further consent is required from parents or guardians). Despite section 8, the court still retains the right to override consent given or withheld by a child over 16 on welfare or best interests grounds in very limited and well defined circumstances (see Re W (A Minor)(Medical Treatment: Court’s Jurisdiction) [1993] Fam 64 (Re W).

With regard to the instruction of experts in family cases, the court has to be satisfied that this is ‘necessary’ and where ever possible provided by a single joint expert (see r.25.12 of the Family Procedure Rules 2010).

The court agreed that it was necessary to instruct an expert endocrinologist, and that should be B’s choice of Dr Cotterill, noting at para 38

…the evidence before the court demonstrates that B is currently receiving HRT in the form of spironolactone and oestrogen. The parents seek to prevent B from continuing with that treatment. Within this context, the court does not have expertise on the benefits and risks of HRT used as “cross-sex hormone” gender affirming treatment. Further, the court has no expertise on the benefits and risks of ceasing such treatment after it has commenced, or of continuing such treatment once it has commenced.

Dr Cotterill had been instructed in other cases in this country and could report in 2 weeks. The court noted at para 41

An expert who focuses on the relevant science and medicine and its impact or otherwise on the subject child, rather than on the wider social, philosophical and political context in which that science and medicine is developing, is likely to be of most assistance to the court, having regard to the role of a jointly instructed expert and the duties of that jointly instructed expert under FPR 2010 Part 25. None of this is to impugn the work of Professor Dahlgren and her informed point of view, but rather simply to prefer the expertise and clinical focus of Dr Cotterill on the facts of this case.

The court did not agree that this case was part of a ‘special category’ where a second opinion should be allowed as a matter of course (para 43). The parents could make further application to the court after receiving Dr Cotterill’s report if they considered it was necessary to request a second opinion. The court would also limit the questions to the expert, as the parents’ questions went more to the merits and consequences of gender affirming treatment generally, rather than the impact on B.

But with regard to the instruction of a psychiatrist, the court noted that he parents wanted the court to ‘examine wider questions of policy with respect to gender affirming treatment’ (para 25). The court reminded itself of what the Court of Appeal said in O v P – matters of policy regarding this treatment are for the NHS, the medical profession, the regulators and Parliament. This case was not a forum for determining the wider political, social or philosophical questions arising from the treatment.

The parents had not provided the court with any evidence that B lacked capacity to consent to taking hormones, other than expressing ‘concerns’ about his mental health and doubt as to whether he had been fully informed of the risks. But the court noted that B had litigation capacity to instruct his own solicitors and he wished the court to know he found it ‘insulting’ to have his capacity questioned in this way.

The court did not find there was cogent evidence that B had mental health difficulties to an extent that would impact his capacity. The court balanced the diagnosis of the CAMHS psychiatrist that B had gender incongruence against the parents’ strongly held views that gender affirming treatment would be inevitably harmful and considered that it would have an adverse impact on B to direct an assessment that he is ‘vehemently against’ (para 36). The court therefore declined to instruct a psychiatrist.

The court’s conclusion is firm at para 47

Finally, and to repeat, this case is and always will be about only one thing. Namely, B’s best interests. This is not, as it has been described in some correspondence the court has seen, a “landmark” case. It is already difficult for a young person when their parents decide to engage lawyers and commence litigation as a means of challenging their choices. Those difficulties can only be enlarged if attempts are made to use such already emotionally charged family litigation as a collateral means of addressing matters of policy with respect to gender affirming treatment that are properly the province of the NHS, the medical profession, the regulators and Parliament. The court will not permit that to happen.

Commentary

It is reassuring to see that the court, indeed both parties, agreed that it was necessary to have some expert medical evidence about the impact of cross sex hormones. I also agree that the court is right to warn against using the welfare of an individual child to wage war on a broader ideology. I agree that the courts cannot overstep into matters which are rightly left to Parliament or the good sense of individual doctors.

But. That doesn’t mean the wider setting of these issues can simply be ignored and this is particularly relevant with regard to the issue of capacity to consent to this treatment. The courts should have no doubt following the Cass Review and the investigations into the Tavistock, that this is a field of medical intervention with children that has itself been hijacked by ideologues. The family court remains the last defence of children who have been dangerously let down by medical and social work professions that have rushed to ‘affirm’ any child’s bare wish to ‘change sex’, despite the lack of any compelling evidence that medical interventions have a positive benefit. This is obvious from the response of the Government to banning puberty blockers and now consulting on the wisdom of providing cross sex hormones to children over 16.

It is disappointing to see no discussion at all in the judgment of the Court of Appeal’s reasoning in O v P as to why the court should continue to have oversight over the provision of cross sex hormones, even to a child with presumed capacity to consent. The Court of Appeal were able then to recognise the rapidly changing ground beneath their feet and the need for caution – why couldn’t this Judge?

And of course, in O v P the 17 year old child in that case was found to be articulate and intelligent just like B – but it was later revealed that the child in conspiracy with her father had set out to deceive the court and the Guardian and had been taking hormones for many months. I note that B was also dishonest in forging his mother’s signature to get his hormones on prescription.

Of course one may be dishonest and have capacity, but in my view, that both children were willing to engage in such deceptions is a measure of how significantly matters have spiralled out of control in this field, where those who have decided that this is what they want to do cannot or will not hear any cautionary voice. This is a very dangerous place to lead children.

I was reminded of a comment at the Genspect conference in Lisbon in September 2025, that stuck with me. Parents were often simply dismissed as ‘transphobic’ by medical professionals, but it was forgotten that it was usually only the parents who saw the whole arc of their child’s life and worried about it.

There is a huge and broad canvass of worry and doubt over what is being done to children in the name of ‘gender identity’. It is difficult for me to see how any child has the capacity to consent to a course of treatment that is unevidenced and irreversible. It is not meddling in policy for a court to agree that great caution is needed here. The fact that a child simply refuses to engage in a psychiatric assessment is not an indication that one is not needed (I would argue the reverse), however I agree it makes it practically difficult to arrange.

Of course, the court should never be asked to determine who is on the ‘Right Side of History’ as this cannot be their role in a democratic society. We have to leave the creation of law and policy to the elected politicians.

But the court interprets the law and it cannot do so in a vacuum. Any court dealing with the welfare of a child ought to be willing to consider the wider negative impact of unevidenced and dangerous medical practice in this field on a child’s ability to offer informed consent. That is neither playing God nor dabbling in policy decisions but rather doing the job with which the High Court is entrusted – to exercise the ancient parens patriae jurisdiction to secure the welfare of every child before it.