This is a post by Sarah Phillimore

‘A patient is the most important person in our hospital. He is the purpose of it. He is not an outsider in our hospital, he is part of it. We are doing a favour by serving him, he is doing us a favour by giving us an opportunity to do so’

Mahatma Gandhi

I would like to consider a variety of reports that have come to my attention recently. These are

The Needs and Challenges of Adoptive and Special Guardianship Families – Working Together to Help Our Children report from June 28th

Children’s Commissioner’s report on vulnerability – July 2018

Working together to safeguard children – updated 4th July 2018

The Needs and Challenges of Adoptive and Special Guardianship Families is a report produced by a group of parents who are either Special Guardians or who have adopted children. Their chair comments:

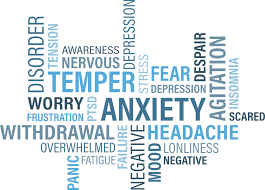

I can see deep systemic problems that affect adopters, and special guardians, which is why we have joined forces. These same problems seem to impact on families where a child has disabilities and special needs where services are required. Austerity has made support harder to achieve, and whether it is from health, education or social care, it so much more difficult to obtain from cash strapped local authorities looking to save wherever they can. We, who rely on services, bear the brunt of austerity, and at the same time can find ourselves victimised by a blame culture that makes us, and our children, extremely vulnerable when our children have behavioural problems and anxiety issues.

Key points from the report

In summary, the report considers the families needs and challenges and their experiences of working together with professionals.

- Over 500 parents and carers were involved in providing information. Two surveys were conducted and four cases were chosen from group members where children had re-entered care to look at children and lives in context.

- Over 700 children were part of these families, many facing very difficult challenges; a high level of disability, numerous complex trauma related mental health problems and life-long conditions such as autism and FASD.

- Parenting children with such serious needs can make family life difficult and respite was identified as ‘vital’ but often not available or hard to come by.

- Parents had mixed experiences of working with professionals. Bad experiences deterred adopters and special guardians from help seeking and made them feel frightened of social services.

- Parents felt that injustices are not adequately scrutinised by the Family Courts as their limited remit is insufficient for such complex cases. The adversarial court system cannot easily ‘problem solve’ and is unable to compel local authorities who do not allocate professionals with adoption or special guardianship expertise to the support of children and families.

The report identified no models, or good practice guidance to assist the safe rehabilitation and reunification of adopted and special guardianship and concluded that this does not seem to be a priority for local authorities.

The report recommends that

- more ethical policies can be developed through the proper involvement of those with‘lived experience’ at a decision-making level in future.

- setting up a Task Force to develop practice guidance for when a child re-enters care to enable relationships between family members to be better supported and develop models for reunification for children where family members are part of the solution rather than part of the problem.

The fundamental point, it appears to me is this:

it is certainly time to have dialogue with those who lives are affected by legislation when the courts cannot be ‘problem solving’ as they should be, when problems are very complex.

Report of the Children’s Commissioner

I do not think there is much, if anything, in this report from the Special Guardians and Adopters with which I disagree. I have been commenting for some time now on the particular pressures that come to bear upon the whole system of child protection which render it arguable ‘not fit for purpose’. See for example this post on ‘Forced Adoption’.

Its broader concerns that the current system does not work well to support vulnerable children and families, are supported by the recent report of the Children’s Commissioner which sets out in stark terms what is being faced by the child protection system. This report found:

The 2.1 million children growing up in families with these complex needs includes:

- 890,000 children with parents suffering serious mental health problems

- 825,000 children living in homes with domestic violence

- 470,000 children whose parents use substances problematically

- 100,000 children who are living in a family with a “toxic trio” (mental health problems, domestic violence and alcohol and/or substance abuse)

- 470,000 children living in material deprivation

- 170,000 children who care for their parents or siblings

Anne Longfield, the Children’s Commissioner said

Over a million of the most vulnerable children in England cannot meet their own ambitions because they are being let down by a system that doesn’t recognise or support them – a system that too often leaves them and their families to fend for themselves until crisis point is reached.

“Not every vulnerable child needs state intervention, but this research gives us – in stark detail – the scale of need and the challenges ahead. Meeting them will not be easy or cost-free. It will require additional resources, effectively targeted, so that we move from a system that marginalises vulnerable children to one which helps them.

“Supporting vulnerable children should be the biggest social justice challenge of our time. Every day we see the huge pressures on the family courts, schools and the care systems of failing to take long-term action. The cost to the state is ultimately greater than it should be, and the cost to those vulnerable children missing out on support can last a lifetime.

“We get the society we choose – and at the moment we are choosing to gamble with the futures of hundreds of thousands of children.”

About the same time as this report, the revised Working Together guidelines were published – this is a lengthy document of 112 pages. Small wonder its so dense, as it makes the clear point that there are a large number of different agencies/organisations who must be putting the child at the centre of their thinking and are under statutory obligations to do so. Under the heading ‘Identifying children and families who would benefit from early help’ it says:

Local organisations and agencies should have in place effective ways to identify emerging problems and potential unmet needs of individual children and families. Local authorities should work with organisations and agencies to develop joined-up early help services based on a clear understanding of local needs. This requires all practitioners, including those in universal services and those providing services to adults with children, to understand their role in identifying emerging problems and to share information with other practitioners to support early identification and assessment.

Conclusion

We all know what we need to do. Children need to be at the centre of our thinking, while respecting the principle that children’s welfare must be seen in the context of their families and communities; families ought to be supported to look after their children rather than the first assumption being that they are places of sinister evil from which children must be ‘rescued’. A stitch in time saves nine, for want of a nail the battle was lost etc etc so we ought to be doing what we can as early as we can because fire fighting is a lot more costly than dealing with problems prior to your house burning down.

But all of this requires time. Time for professionals to build relationships of trust with children and families so they don’t simply become troublesome units to be risk assessed and dealt with in a way that will save agencies from adverse comment down the line. And it requires money. To pay enough professionals to have enough time to be able to identify services and support that could actually help. To devise a coherent strategy of intervention that does not see children and family bounced from a variety of services and individuals.

It is really good that we are talking, and that more efforts are being made to cross professional boundaries. But I am still worried from what I read and hear about the debate around child protection that the compulsion to polarise, to find a ‘gang’ and be part of it remains very strong. Social workers are either ‘corrupt liars’ or parents are ‘monsters’. I have written on many occasions about the dangers of naive or wilfully misinformed allegiance to a position at the expense of actual fact. See as just one example, Linda Arlig, her hammer and some nails.

But the mess we are currently in is not the product of just one profession or one political persuasion. its been building up over many, many years. It is becoming increasingly urgent to translate talk into action. It is particularly difficult when the court and legal system has become, since the Children and Families Act and the 26 week time limits, part of that framework of potential oppression.

Possibly hypocritically in light of the above, I hope that if you have read this far you will consider joining me and many others on September 15th at the Conway Hall in London to discuss the issue of ‘future emotional harm’ as a justification for removing children from parents. This has been for many years a particular bug bear of parents and not something I think is well understood, even by professionals. The focus of the day will be conversation between what I hope will be a large number of different groups – parents, lawyers, social workers, care leavers – with the aim to turn conversation into action.

Further reading

Abuse and neglect – how is it identified and what support is offered? Post from parent October 2017

Care Crisis Review 2018 Family Rights Group

The Adoption Enquiry BASW – their website is down! but you can read my post about it here.

MP Tim Loughton, a former Tory children’s minister has blamed the government’s “woeful underfunding” of local authorities for a crisis in child protection that is putting the safety of vulnerable young people at risk. vThe Guardian, July 11th 2018.

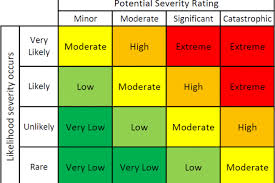

Storing up Trouble – July 2nd 2018 report from All-Party Parliamentary Group for Children (APPGC) following September 2017 inquiry into the causes and consequences of varying thresholds for children’s social care. The inquiry found:

- Vulnerable children face a postcode lottery in thresholds of support

- 4 in 5 Directors of Children’s Services say that vulnerable children facing similar problems get different levels of help depending on where they live.

- Children often have to reach crisis before social services step in.

- Decisions over whether to help a child, even in acute cases, are influenced by budget constraints.

- Children and young people in care and care leavers highlighted the difficulty they faced gaining insight into their personal histories. They called for better support in accessing and understanding information contained in official files.

Summary of the changes to the Working Together Guidance from the NSPCC