I was asked by the journalist Louise Tickle to consider whether or not she would be in contempt of court if she published a blog post detailing her frustrations with the way the family court had dealt with a recent application made by a number of journalists.

In brief, the journalists attended a final hearing which had come about due to a decision made by the Court of Appeal that has already been reported and is in the pubic domain. That judgement names the relevant LA and social worker and provides personal detail about the mother, including her ethnicity and the date of birth of her child. What the journalists wanted to do was to report on the final hearing but also link in their reporting to this published judgment as otherwise it was difficult to understand how the case had taken the shape it had.

The Judge at the final hearing was not minded to permit publication of anything that might identify the ethnicity of the mother nor the identities of any professional parties – which poses the immediate problem that no reference could then be made to the prior judgment already published which contained that information.

Louise was unhappy with this outcome and I had to agree it was deeply unsatisfactory. I have not held back criticising journalists who refuse to link to judgments or even read them and end up publishing something partial and inaccurate. Therefore I am troubled to be told that journalists who wished to report by reference to the actual facts already in the public domain were being told that they may not – and even worse, that their right to freedom of expression from Article 10 of the ECHR, did not appear to be given any proper consideration by the Judge or the other advocates.

I read Louise’s proposed blog post and ran this past my understanding of the consequences that followed from applying section 12 of the Administration of Justice Act. My analysis of the law follows below.

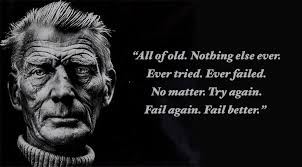

I don’t think Louise is going to be hauled before a Judge and found in contempt of court for publishing her blog. But I didn’t feel that I could offer robustly confident advice that she would not. It is clear that each case will turn on its own facts and thus there is very little guidance for the lay person or lawyer who doesn’t deal with such matters on a regular basis – which I imagine is all of us.

For so long the family court have operated without public scrutiny that I do not think it is common place for Judges to be asked to consider relaxing the requirements of section12 AJA in general run of the mill family cases.

I hope I am right about all this. But I am not sure. It seems a rather unsatisfactory state of affairs that public comment about the family justice system should operate under such a climate of fear. Being found in contempt of court is a serious business; one possible punishment is the loss of your liberty. When facing serious consequences, the law that imposes them needs to be clear and it needs to be accessible. Lawyers need to understand and apply the necessary balancing exercise between Articles 8 and 10. How many do?

I do not think that our law about reporting matters in the family court is clear, accessible or consistently applied and .I will follow developments here with interest. Louise has launched a crowdfunder to raise the costs of her proposed appeal.

My view of the law.

Section 12 of the Administration of Justice Act 1960 forbids the publication of information relating to proceedings under the Children Act 1989 or the Adoption Act 2002. There is no time limit so the prohibition operates even after proceedings end.

Sub section (2) of the AJA exempts ‘the publication of the text or a summary of the whole or part of an order made by a court sitting in private’ UNLESS the court expressly prohibits the publication. There is no other exemption or explanation of terms offered by the statute.

We therefore need to look to case law and other general principles to understand what is meant by ‘information’.

With regard to publication, something is ‘published’ whenever it would be considered published according to the law of defamation UNLESS someone is communicating information to a professional in order to protect a child. A blog post published on the internet would thus clearly meet the definition of publication and by publishing a general blog, Ms Tickle could not avail herself of the defence that she is communicating to a professional.

Publication of “the nature of the dispute”, which is permissible, and publication of even summaries of the evidence, which is not.

What is meant by ‘information’? Munby J (as he then was) considered this in Re: B (A Child) (Disclosure) [2004] 2 FLR 142. He identified classes of information falling into this category as likely to be [para 66] :

- accounts of what has gone on in front of the judge sitting in private

- documents such as affidavits, witness statements, reports, position statements, skeleton arguments or other documents filed in the proceedings,

- Transcripts or notes of the evidence or submissions, and transcripts or notes of the judgment. (I emphasise that this list is not necessarily exhaustive.)… likewise…extracts or quotations from such documents…also the publication of summaries

The identity of witnesses in care proceedings is not protected by section 12 and if any witness does want to remain anonymous they will have to convince the court that their need for anonymity was more important than the need for openness.

Section 12 does not prevent publication

- of the fact that proceedings are happening, or

- Identification of the parties or even of the ward himself. EDIT BUT PLEASE NOTE THAT s97 of the Children Act forbids naming children in current care proceedings.

- or the comings and goings of the parties and witnesses,

- or incidents taking place outside the court or indeed within the precincts of the court but outside the room in which the judge is conducting the proceedings.

However. at para 77 Munby J poses his final question ‘the extent to which section 12 prohibits discussion of the details of a case’. It is likely to be this question that is of most interest to Ms Tickle. He found he was assisted by Wilson J’s analysis in X v Dempster. There the question (see at p 896) was whether there was a breach of section 12 by publishing the words:

“Says a friend of [the mother]: “She has been portrayed as a bad mother who is unfit to look after her children. Nothing could be further from the truth. She is wonderful to [them] and they love her. She wants custody of [them] and we will see what happens in court”.”

Wilson J commented:

I am satisfied that the reference to the portrayal of the mother in the proceedings as a bad mother went far beyond a description of the nature of the dispute and reached deeply into the substance of the matters which the court has closed its doors to consider. If the reference could successfully be finessed as a legitimate identification of the nature of the dispute, the privacy of the proceedings in the interests of the child would be not just appropriately circumscribed but gravely invaded.

Munby J agreed with this observation and concluded:

Every case will, in the final analysis, turn on its own particular facts. The circumstances of the human condition, and thus of litigation, being infinitely various, it is quite impossible to define in abstract or purely formal terms where precisely the line is to be drawn. Wilson J’s discussion in X v Dempster, if I may respectfully say so, comes as close as anyone is likely to be able to illuminating the essential distinction between publication of “the nature of the dispute”, which is permissible, and publication of even summaries of the evidence, which is not.

Consideration of the case law when applied to Ms Tickle’s proposed blog

For a lawyer asked to give advice, the heart sinks upon encountering the phrase ‘every case will, in the final analysis, turn on its own particular facts’. This clearly makes it difficult to offer firm advice.

It is my view that the thrust of the blog post is very clearly to highlight Ms Tickle’s understandable frustration with what seems like a wholly inadequate approach by the court to the necessary balancing exercise of ECHR Articles 8 and 10. I do not think that anything she proposes to publish will fall foul of the distinction identified in X v Dempster. The ‘dispute’ which she wishes to highlight is in fact removed from the actual facts of the care/placement proceedings before the court and is a dispute about an ancillary matter; the relaxation or otherwise of reporting restrictions given that risk (I assume) of jigsaw identification once any reporting of this matter is linked to an earlier Appeal Court decision already in the public domain.

I must stress to Ms Tickle that in offering my opinion as I do, cannot be seen as any kind of guarantee that she would NOT face proceedings for contempt arising out of her blog post. It may be that my opinion is not shared by a Judge hearing this matter. However, I reflect upon the fact that she has clearly taken great care to strip any identifying details from the blog. In my view it is unlikely that any such proceedings would be bought; I would consider them wholly disproportionate in all the circumstances. In my view, the LA is the only party likely to consider such action and I would hope they have better things on which to spend their time and money.

Further reading

The opposite of transparency – an appeal against a reporting restrictions order Louise Tickle’s post on the Open Family Court website.

For a more general discussion of the principles around transparency in the family court see this post

Or visit The Transparency Project website.