This post looks at the legal and practical difficulties parents may face if they disagree with doctors or social workers about the medical treatment their child needs. Doctors cannot examine or treat anyone without getting consent, unless the situation is life threatening and urgent. Medical intervention can range from the trivial to the really serious and the further up the scale of intervention you go, the more likely you are to encounter disagreements about the best way forward. Who gets to decide and how?

The case of Ashya King

For more detail about Ashya King’s case see this post from the Transparency Project.

The issue of managing disagreements between parents and doctors came to the fore in September 2014 with the case of Ashya King, a five year old boy who was being treated for cancer in the UK. His parents and the hospital could not reach agreement about the best treatment options for Ashya; his parents removed him from the UK to seek treatment abroad and were then arrested after the hospital informed the police and the local authority (LA) of their disappearance.

The LA applied for Ashya to be made a ward of court, which meant that no decision could be taken about his treatment without permission from the court. Upon arrest, Ashya’s parents were kept apart from their son for several days. The case caused enormous concern both in the UK and internationally. Of particular concern is the parents’ view that they had no choice but to leave in the way they did as they were alarmed by the hospital suggesting that the LA would need to get involved, even to apply for an emergency protection order. It is clear that the working relationships between the parents and the doctors must have seriously deteriorated, if not broken down completely.

When the case came before Baker J on September 8th he discharged the wardship. He found that the earlier decision to make Ashya a ward of court was justified on the information that the court had before it. But now the position had changed; there was a clear treatment plan which was not opposed by either the LA or Ashya’s guardian. The Judge could not comment on the desirability of issuing a European arrest warrant which resulted in the parents’ detention, but commented that it was clearly not in Ashya’s best interests to have been separated from his parents.

So what happens if you disagree with the treatment proposed by professionals?

The importance of consent.

The fundamental principles of consent were discussed in the case of A (Children) [2000]. Every adult person of sound mind has the right to say what can and can’t be done to his body. Without consent, medical examinations or procedures are unlawful – they are either the criminal offence of assault or the civil offence of trespass to the person. Therefore it is very clear that consent must be given to any kind of treatment or examination unless its an emergency and doctors say they had to act out of ‘necessity’.

Consent is only valid if it is:

- voluntary – given freely;

- informed – understanding the implications of consenting;

- and the person giving it has capacity – they are capable of making decisions.

Who does not have capacity?

A ‘child’ is defined in the Children Act as a person between the ages of 0-18 years, but it’s really important to distinguish between children who are 16 and older as 16-17 year olds can provide consent to treatment as if an adult.

- Children under 16, unless found to be ‘Gillick competent’ do not have the capacity to consent to treatment. A child will have capacity only if he or she is able to understand the nature, purpose and possible consequences of the treatment proposed. For a useful discussion of issues that arise around understanding and capacity see the article about transgender children in Further Reading below.

- Adults or children over 16 years, may not have capacity as defined by the Mental Capacity Act 2005, if they can’t make their own decisions because of some problem with the way their brain or mind is working. This could arise due to illness, disability or exposure to drugs/alcohol. It doesn’t have to be a permanent condition.

An example of a situation where an adult was found not to have capacity to consent to medical treatment, is the ‘forced C-Section’ case of 2013 (see P (A Child) [2013) where the pregnant mother was experiencing serious mental health difficulties and the hospital were concerned about the risks of a natural birth in such circumstances.

Who do doctors ask if the patient doesn’t have capacity?

They will need to get:

- consent from someone who has parental responsibility (PR) for the child; or

- permission from the court in the case of an adult who lacks capacity or where there is a dispute between adult carers of the child.

Parental Responsibility

Parental responsibility is defined at section 3 of the Children Act 1989. The British Medical Association (BMA) ethics guidance from 2008 describes PR in these terms:

- Parental responsibility is a legal concept that consists of the rights, duties, powers, responsibilities and authority that most parents have in respect of their children. It includes the right to give consent to medical treatment, although as is discussed below, this right is not absolute, as well as, in certain circumstances, the freedom to delegate some decision-making responsibility to others. In addition, competent children can consent to diagnosis and treatment on their own behalf if they understand the implications of what is proposed (see below). Those with parental responsibility also have a statutory right to apply for access to the health records of their child, although children who are mature enough to express views on the issue also need to be asked before parents see their record. Parental responsibility is afforded not only to parents, however, and not all parents have parental responsibility, despite arguably having equal moral rights to make decisions for their children where they have been equally involved in their care.

In theory, doctors only need consent from one person with PR to go ahead with treatment. However this will rarely be a wise course of action if there are strong objections from others who have involvement in the child’s upbringing. The best ethical option in cases of dispute, is to apply to the court for an order to either allow or refuse the treatment in question.

An example of such application to court can be found in the case of Neon Roberts, whose parents disagreed about the best way to treat his cancer. Parents may also disagree about specific medical interventions, such as circumcision or blood transfusions on religious grounds.

While the parties are waiting for a court decision regarding treatment, doctors should only provide emergency treatment that is essential to preserve life or prevent serious deterioration of health.

If the doctors consider that by refusing consent to treatment you are not acting in your child’s best interests, they will need to raise this issue with the LA who may need to consider issuing care proceedings.

Further information for doctors and patients.

The British Medical Association (BMA) publishes guidelines and can be contacted for advice.

- BMA members may contact: 0300 123 1233 or British Medical Association Medical Ethics Department BMA House, Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9JP Tel: 020 7383 6286 Email: et****@*****rg.uk.

- Non-members may contact: British Medical Association Public Affairs Department BMA House, Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9JP Tel: 020 7387 4499 Email: in*********@*****rg.uk

What if I am sharing PR with the LA?

If a care order has already been made then you share PR with the LA. It is clear that it would be unwise for doctors to feel they need only seek permission from the LA, particularly if the proposed treatment is significant. Efforts should always be made to reach agreement, particularly if the proposed medical intervention is not going to involve significant impact on a child’s bodily integrity.

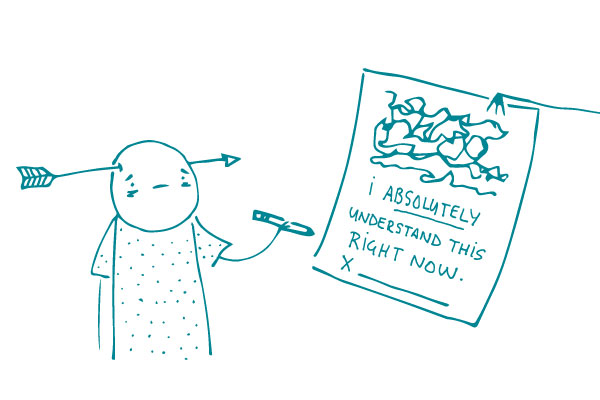

If you don’t feel able to agree to relatively simply medical procedures or assessments, that may raise question marks in the minds of the professionals about how you are discharging your parental responsibility. It is not difficult to see how such situations can spiral out of control (as in the case of Ashya King above) with parents being very suspicious of doctors and vice versa. As ever, good communication is the key; if you are worried about a particular procedure, say so and say why. Ask for further explanation and discussion.

If agreement just isn’t possible, again applying to court may be the only option. The LA cannot simply make any decision they like even when they do share PR under a care order. They can only act when it is ‘necessary’ to safeguard or promote the child’s welfare. See section 33(4) of the Children Act 1989 and considerations of proportionality under Article 8 of the ECHR. The LA also remain under a duty to consult parents before making any serious decisions about a child who is subject to a care order.

See this case from 2013 where Kingston on Hull City Council were subject to a successful judicial review of their failure to consult parents. The Judge made clear at paragraph 58 his views about the duty to consult:

- I have made it clear that there is a duty upon a local authority to consult with all affected parties before a decision is reached upon important aspects of the life of a child whilst an ICO is in force. I have been shown the guidance issued by HM Government to local authorities in 2010 [The Children Act 1989 Guidance and Regulations] where there is valuable material available to social workers about how to approach their difficult task in this regard. Paragraph 1.5 provides (inter alia): “Parents should be expected and enabled to retain their responsibilities and to remain closely involved as is consistent with their child’s welfare, even if that child cannot live at home either temporarily or permanently.” … “If children are to live apart form their family, both they and their parents should be given adequate information and helped to consider alternatives and contribute to the making of an informed choice about the most appropriate form of care.”

Principles of law when there is disagreement about the treatment a child needs.

If it is not possible to reach agreement, the court will have to make a decision about what kind of treatment/intervention is in the best interests of the child. Baker J set out the relevant principles to be applied in such cases (see para 29 of his judgment in September 2014):

- The child’s welfare is the most important issue before the court ;

- The court must also have regard to the child’s rights under the ECHR; most pertinently the right to life under Article 2 and the right to respect for family and private life under Article 8;

- Responsibility for making decisions about children rests with the parents and the state should only interfere if the child is suffering or at risk of suffering significant harm.

For consideration of how the court should approach a case when doctors wish to stop giving life sustaining treatment to a seriously ill child, see the case of Kirklees Council v RE [2104].

Further reading

Children of Jehovah’s Witnesses and adolescent Jehovah’s Witnesses: what are their rights? BMJ 2005

Girl of 13 allowed to refuse heart transplant – The Independent November 2008

Parents with child in care cannot object to the LA deciding to immunise their child, using section 33 of the Children Act – The Guardian April 2020

In Who’s best interests? The transitioning of preschool children – Sarah Phillimore October 2019

Transgender Children: limits on consent to permanent interventions Heather Brunskell-Evans January 2020

GIDS deploys three Gillick Competence criteria to assess whether a child under 16 can give informed consent.

The first criterion is that the child has the mental capacity to fully understand the likely consequences, both positive and negative, of her decision-making. However, she or he is not psychologically competent to assess the likely consequences of a complex and contested medical area whose future ramifications will have little or no meaning. Not only are all the long-term impacts of hormone therapy unknown to clinicians themselves, a child will have little or no cognisance of a future in which she or he will become a medical patient for life, may come to regret lost fertility (including, for example, the lack of breasts, ovaries and uterus), and the lack of organs for sexual pleasure.

Moreover, the information given by GIDS to children is simply not factual. For example, children are told that hormone blockers will make them feel less worried about growing up in ‘the wrong body’ and will give them more time and space to reflect. This reassurance is contradicted by GIDS’ own recognition that research evidence demonstrates that after one year young people report an increase in body dissatisfaction; rather than giving the opportunity to change their minds children almost invariably proceed to cross-sex hormones.