On Saturday 15th September The Transparency Project supported the third Child Protection Conference and Bath Publishing kindly sponsored, thus ensuring those attending had some biscuits and some reading materials.

I will publish here below my presentation at the conference and will shortly publish a summary of what was said by all the speakers and the audience. As ever, thanks go to those who came to speak and also those who were prepared to listen. In honour of Lady Hale – the one dissenting voice in the Supreme Court in judgement of Re B – I wore her face on my chest for the day.

The aim of #CPConf2018 was not only to launch The Transparency Project’s Guidance note on the use of experts in family proceedings, but to begin the discussion on what would be needed for a further Guidance Note about how risk assessments are carried out, and how we can best understand them and challenge them if needed.

The Children Act 1989 and the introduction of ‘risk of future emotional harm’.

1. The 1989 Act was born following:

(1) a review by the Law Commission of England and Wales of the private law relating to the guardianship and upbringing of children (culminating in Law Com No 172, [1988] EWLC 172, Review of Child Law: Guardianship and Custody, 1988) and

(2) an interdepartmental review, led by the Department of Health and Social Security, into the public law relating to child care and children’s services (Review of Child Care Law: Report to ministers of an interdepartmental working party, 1985, HMSO).

2. The aim was to replace the existing ‘complicated and incoherent system’ with “a simplified and coherent body of law comprehensible not only to those operating it but also to those affected by its operation” (Second Report, Session 1983-84, Children in Care, HC 360).

3. It was considered to be a benefit to the new legislation that it was prepared to look to the future and protect children against a serious risk that they would suffer future harm, rather than waiting until actual harm had occurred until taking action.

4. However, it is clear we still have serious problems;

(1) identifying emotional harm,

(2) agreeing how serious it is and

(3) assessing the risk of it happening in the future.

5. There is no doubt that ‘emotional harm’ has been found to have really serious impact on children as they grow. Note for e.g. N. Hickey, E. Vizard, E. McCrory et al., Links between juvenile sexually abusive behaviour and emerging severe personality disorder traits in childhood, (Home Office, Department of Health and National Offender Management Service, 2006).

6. However, there are infinite number of variables about people’s behaviour and their reactions to it. We can agree that somethings are generally bad all of the time – for example, hitting or shouting at a child on a day to day basis. But some children grow up ok, possibly due to having other safeguards in place, supportive school or grandparents etc. It is simply not possible to provide a catch all definition of ‘Emotional harm’ and predict with much certainty what impact will be born by each individual child.

7. the concept of emotional harm, let alone future emotional harm, seems to cause a lot of people unease and disquiet. Either they don’t understand it or they think it misused – I suspect both. I recall the French documentary makers of ‘England’s Stolen Children’ were utterly horrified by it, calling it a concept ‘unknown’ to legislation elsewhere.

8. To me this is the crucial point – law must exist to serve the people, not impose shadowy misunderstood and misapplied concepts upon them. Professor Devine and many others make the point that our current system of child protection is seen through a lens of risk which clearly impacts on how social workers will assess the situation before them. There is abundant evidence that the language we use impacts on the way we think about a situation – note the work of Professor Kelly at the Harvard Medical School who experimented with two different descriptions of someone addicted to drugs. One was “substance abuser,” the other described as having “substance use disorder. When testing these phrases with both doctors and the general public, both groups displayed much more punitive attitudes towards to the ‘substance abuser’.

9. I also note that ‘emotional abuse’ of children is NOT currently covered in the criminal law, for example. See Children and Young Person’s Act 1933. There were calls for reform in 2013 stating this law was not fit for purpose as based on historic and outdated understanding – see ‘The criminal law and child neglect, independent analysis and proposals for reform’ Action for Children 2013. But I don’t know what if anything is happening – I suspect not.

10. The amount of care cases involving emotional harm is clearly growing so there is an urgent need to be clear about how it is identified and how we make decisions about how serious it is or could be. NSPCC statistics show neglect cases rising from 17,930 in 2013 to 24,590 in 2017; emotional abuse from 13,640 to 17,280.

11. All of this I hope we can discuss today. I would like to touch briefly on what happened in the Supreme Court decision of Re B in 2013 as this is such an important decision that sets the scene for the current law and practice. Lucy Reed is going to discuss further the lawyer’s perspective about how the current law is operating.

FUTURE EMOTIONAL HARM – the SUPREME COURT PERSPECTIVE

12. Guidance from Re B 2013 UKSC

13. ‘Amelia’ was born in April 2010 and immediately removed from her parents’ care. This case is described by Julie Doughty (rightly) as:

‘A remarkable case where a child is to be adopted although she has not suffered any harm attributable to her parents, both of whom have established and maintained positive contact with her for more than 2 years since she was removed at birth’.

Julie Doughty (2013) Re B (A Child) (Care Order) (2013) UKSC 33, Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law

14. The concerns about the parents and particularly the mother were based on their past behaviours. The mother had been involved in a dysfunctional relationship with her domineering step-father who started having sex with her when she was only 15, resulting in 6 abortions and one child, who was also taken into care in 2011. She had several criminal convictions for offences of dishonesty. She had been diagnosed as having somatisation disorder, a psychiatric illness in which the sufferer makes multiple complaints to medical professionals for which no physical explanation can be found. She was found to be a ‘pathological liar’ and continued making serious false allegations against a variety of people even when no longer under the malign influence of her step father.

15. The father had 52 criminal convictions dating from when he was 13 and was very unwilling to co-operate. For example, rather than agreeing to take a drugs test in 2010, he told the LA to ‘kiss my arse’ until eventually agreeing in July 2011 – thus contributing to a year’s delay for decisions about his daughter. (This could not happen now of course – the 26 week timetable would have meant the final care order being made no later than October 2010!).

16. The court decided in 2012 after a 15 day hearing, with evidence from a variety of experts, that Amelia should be adopted. This was on the basis that although Amelia had suffered no actual harm in care of her parents and they had been able to maintain a positive and loving relationship with her over 2 years of supervised contact, if she went to live with them, there was a serious risk that neither parent could create and maintain a safe environment for her as she was growing up.

17. There are obvious worries about this case – any case that gets to the Supreme Court is raising clear and serious issues of general public importance. Although the Court of Appeal upheld the decision of the first judge on the basis that his judgment was ‘long, detailed and careful’, they found the case ‘troubling’ as an example of state intervention regarding a ‘much loved child’ in the subjective area of moral and emotional risk, rather than physical abuse. The famous statement of Hedley J is relevant again; Re L (Care Threshold Conditions) [2007] 1 FLR 2050 para 50

Society must be willing to tolerate very diverse standards of parenting, including the eccentric, the barely adequate and the inconsistent… it is not the provenance of the state to spare children all the consequences of defective parenting’.

18. So the case continued to the Supreme Court. The appeal was dismissed but it is important to note both that this was not unanimous and the dissenting Judge was Lady Hale. She agreed, with some reluctance that threshold was crossed but regretted that the first Judge had not explicitly identified what exactly tipped this case over the threshold. It has to be something of character or significance to justify the compulsory intervention of the state.

This case raises squarely the problem of how should courts assess risks that are ‘conditional’ or unrealised?

19. There is a clear worry here that not enough attention was paid to the impact on the parents of the system itself on what worried the judges most about them – their unwillingness or inability to co-operate with professionals.

20. As Julie Doughty comments, Lady Hale was the only judge to refer to facts that made the parents anxieties about Amelia’s health and their distrust of professionals less irrational. For example, that Ameila was born prematurely at 32 weeks and was initially cared for in intensive care. The parents received no ‘pre proceedings letter’ . The mother in particular had escaped a horrifically abusive relationship with her own step father.

21. Lady Hale did not accept that Amelia being adopted was a ‘proportionate’ response to the risk of harm identified. She was concerned that the most drastic option for a child (closed adoption) was the choice in a case where even the first Judge had not found threshold crossed ‘in the most extreme way’.

22. What is also interesting is that the commentary on this case on the Supreme Court’s own website is critical. I note:

As Lady Hale highlighted in her dissenting opinion, this case brings into stark relief another difficult question. When should the state take away a child, not because physical abuse or neglect is feared, but because the character of the parents is such that they cannot help but be deficient parents? What was remarkable about this case is that, though the parents clearly had significant problems, their care of their daughter was held to be highly satisfactory. As parents, they appeared to be competent; as people, apparently less so.

The decision made here is problematic for two reasons.

Firstly, it is based wholly on future harm. The risks identified may never materialise. Further, it is enough that such harm is “possible”; it need not even be “probable”. It is not a perfect comparison, because the one deals with the past whilst the other deals with the future, but it is worth noting that we do not convict people of crimes unless we are “certain so that we are sure” that they have committed them: in contrast, we will take children away from their parents on the basis of a “real possibility”.

Secondly, even if the harm identified does materialise, is it enough? We have decided as a society that, as a general rule, it is more important for children to be brought up in their own families than to be brought up in “better” families. Does the effect of the parents’ dishonesty and mother’s psychiatric illnesses justify removing Amelia permanently from their care? As Hedley J observed in Re L (Care: Threshold Criteria) [2007] 1 FLR 2050, 2063: “Society must be willing to tolerate very diverse standards of parenting, including the eccentric, the barely adequate and the inconsistent”.

23. I am not confident that one can so neatly make a distinction between who we are as ‘people’ and how we are as ‘parents’ – if we are rude, impatient or violent as ‘people’ we are highly likely to display similar traits when wearing our parent hats. ‘How you do anything is how you do everything’

24. However, if more cases are going to be determined on the basis of a risk of something that hasn’t happened yet, and that something is as potentially nebulous as ‘emotional harm’ then we do need to take more seriously the fact that parents appear to be increasingly alienated and confused by care proceedings. This problem is compounded by the very bad advice I have often seen on line about refusing to co-operate. The likely consequences of that refusal is to increase concerns and escalate the probability of serious action being taken, or pessimism about the parents’ abilities to change. Lucy Reed will look at this problem in more detail.

25. Guidance on threshold from the Supreme Court.

(1) Court’s task is not to secure for every child a happy and fulfilled life but to be satisfied the statutory threshold are crossed

(2) This requires the court to identify as precisely as possible the nature of the harm which the child is suffering or is likely to suffer.

(3) This is particularly important where the child has not yet suffered any, or any significant, harm and where the harm which is feared is the impairment of intellectual, emotional, social or behavioural development.

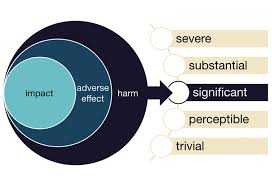

(4) Significant harm is harm which is “considerable, noteworthy or important”. The court should identify why and in what respects the harm is significant.

(5) The harm has to be attributable to a lack, or likely lack, of reasonable parental care, not simply to the characters and personalities of both the child and her parents.

(6) Finally, where harm has not yet been suffered, the court must consider the degree of likelihood that it will be suffered in the future. This will entail considering the degree of likelihood that the parents’ future behaviour will amount to a lack of reasonable parental care. It will also entail considering the relationship between the significance of the harmed feared and the likelihood that it will occur. Simply to state that there is a “risk” is not enough, the harm must be ‘likely’.

Further guidance S & H-S (Children), Re [2018] EWCA Civ 1282 (06 June 2018)

(7) It is good practice to distil findings into one or two short and carefully structured paragraphs which spell out the court’s finding on threshold identifying whether the finding is that the child ‘is suffering’ and/or ‘is likely to suffer’ significant harm, specifying the category of harm and the basic finding(s) as to causation.

(8) When making a finding of harm, it is important to identify whether the finding is of ‘significant harm’ or simply ‘harm’.

(9) A finding that the child ‘has suffered significant harm’ is not a relevant finding for s 31, which looks to the ‘relevant date’ and the need to determine whether the child ‘is suffering’ or ‘is likely to suffer’ significant harm.

(10) Where findings have been made in previous proceedings, a judgment in subsequent proceedings should make reference to any relevant earlier findings and identify which, if any, are specifically relied upon in support of a finding that the threshold criteria are satisfied in the later proceedings as at the ‘relevant date’.

(11) At the conclusion of the hearing, after judgment has been given, there is a duty on counsel for the local authority and for the child, together with the judge, to ensure that any findings as to the threshold criteria are sufficiently clear.

(12) The court order that records the making of a care order should include within it, or have annexed to it, a clear statement of the basis upon which the s 31 threshold criteria have been established.

https://twitter.com/SVPhillimore/status/1040841426194636800