I am very grateful to the mother of Shayla for giving me permission to post this. I shall call the child murdered by Matthew Scully Hicks (MSH) by the name her mother gave to her at birth. It is one of the sad and poignant features of many in this case that at the time of her death Shayla was known by at least four different names, which made it difficult to find relevant records about her short life. Page 15 of the Review notes that ‘at the point of her death it was difficult to get the information about when she had seen medical professionals. This was due in part to a number of different IT systems and that S was known by four different combinations of her birth and adopted name.’

Another more poignant issue is her mother’s belief that, had she been told of Shayla’s injuries when in the care of MSH before the making of the adoption order and when she still had parental responsibility, her baby would still be alive. The mother may or may not be right in that belief. But now, sadly, we shall never know.

What rights do parents have to know their child has been hurt? Even if the parent isn’t caring for their child? Even if there is no chance the parent ever will?

In brief, S was injured on several occasions in the care of MSH before the adoption order was made. Shortly after the adoption order was made he assaulted her again and this time she died. The mother was never told about any of these injuries despite retaining parental responsibility until it was extinguished by the making of an adoption order. She remains of the belief that had she known, there would have been something she could have done to stop her daughter’s death.

Other parents have told me online, and in person, that the same thing has happened to them. That their children suffered sometimes really serious injuries whilst in foster care but they were never told. Just what is going on here? Why is parental responsibility apparently so carelessly ignored when children are looked after? The clue is found in the Review at page 15:

the child while still legally a child looked after, was considered an adopted child and so this shaped the way professionals shared information.’

I suspect what we are seeing here is the logical conclusion of the mantra that ‘adoption is best’ and that ‘children need to be rescued’. If a child is seen entirely in isolation from his or her parents, if those parents are seen as unsuitable or undesirable then it is hardly surprising that their legal rights are not seen as something worthy of much attention. But this is wrong. It hurts both parents and children.

Even if parents cannot care for their children, by reason of circumstances within or without their control, it is rare to find a parent who doesn’t care about them, who doesn’t have knowledge about their child. Even the very ‘worst’ ‘monster parent’ still has something to offer, even if it is only some sense of identity or history.

I do not think what appears to be widespread negation of parental responsibility when children are looked after is acceptable and it says profoundly ugly things about our society.

The review of Shayla’s death.

The only written document I have seen relating to these proceedings is the Extended Child Practice Review C&V CPR 04/2016 (‘the Review’) which was commissioned by the Cardiff and Vale of Glamorgan Regional Safeguarding Board on the recommendation of the Child and Adult Practice Review Subgroup in accordance with the Social Services and Well Being (Wales) Act 2014 Part 7.

What happened between September 2014 and S’s death in 2016.

At page 4 the Review sets out what it is has done and who has been seen in order to complete the work. I note that both the mother and the maternal grandmother were interviewed and the Review explicitly recognises how difficult and emotional it has been for both.

S was placed in foster care in November 2014. A care and placement order were made in May 2015 and S was placed with MSH and his husband in September 2015. The adoption order was made in May 2016 and she died shortly afterwards. MSH was convicted of her murder in November 2017.

The Review sets out the care planning for S at page 6 and concludes it was appropriate; all the evidence suggested that adoption would be in S’s best interests.

MSH and his husband were first approved as adoptive parents in August 2013 and had their first child placed with them in October 2013. The first child was adopted by them in April 2014. They were assessed again in February 2015 and approved in July 2015. In September 2015 the Agency Decision Maker approved the match between S and the adoptive parents and she moved to live with them.

The Review sets out at page 7 that they had access to key documents about this assessment process and considered it was ‘robust, detailed and comprehensive’. All the evidence suggested this would be a positive outcome for the child. There is no mention here of any member of the assessment process or any social worker being related to MSH’s husband. If this is true, I would expect comment.

The Review then considers S’s placement with the adopters. In November 2015 she is taken to the GP by one parent, it is not clear which (reference is made to ‘dad’ or ‘father’ rather than ‘primary carer’ which would have clearly identified MSH) and found to have a fracture to the bone at the end of her left leg. However she is seen only by a Registrar who was not overseen by a consultant; in fact she had two fractures of two different bones in her left leg and this was not discovered until after her death. The doctors, unaware of the second fracture, find the parents’ description of what happened to fit with the injuries found and a cast was put on S’s leg.

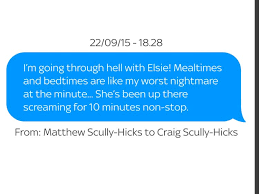

In December 2015 MSH texts the Adoption SW to say S has a large bruise on her forehead. The Adoption Review makes no reference to that bruise. Five days later a health professional notes (presumably) another bruise to her forehead and eye. The health professional does not tell anyone else.

In March 2016 MSH telephones 999 to say S has fallen though the stair gate at the top of the stairs, does not lose consciousness but vomits. S goes to hospital for 4 days. Medical professionals accept MSH’s explanation. S is then seen by a GP for a ‘unilateral squint’. A referral is made but she dies before this can take place.

In May 2016 S is seen by consultant neonatologist for routine follow up and no concerns identified. Later than month MSH calls 999 to say S is limp, floppy and unresponsive. He gives different explanations about what happened. S never regains consciousness and died in hospital with bleeding on her brain. The police arrest MSH.

The Review does identify some serious flaws in these procedures:

a. The bruise(s) to S was not recorded and not considered at the Adoption Review

b. S was not taken to the GP until 5 days after the ‘accident’ that led to the fracture of her left leg and in fact a second fracture to the top of her left leg was identified after she died. It was considered highly unlikely for any child to break two separate bones in one accident and had the second fracture been found at the time, ‘concerns would have undoubtedly been raised and child protection procedures instigated’.

The Review notes that immediate organisational changes were made.. I note at page 15 the Review comments ‘the child while still legally a child looked after, was considered an adopted child and so this shaped the way professionals shared information.’

The Review comments on the mother’s views in the following terms:

The Birth Mother shared her concern that it was several months before she was informed of her child’s death. She indicated that she would have preferred to have been informed of her child’s death by somebody that was known to her. Following being informed, she felt she received information from several sources in an ad hoc fashion. Understandably the emotional impact of the child’s death on the birth family has been very significant.’

However the Review does not appear to make any substantive comment on these issues and how they could be dealt with better in the future. I would have liked to see at least some discussion of that.

At page 12 the Review identifies what they have learned from S’s death. A key point appears to be that although MSH, his husband and some of the extended family knew that MSH was under stress caring for two children, this information wasn’t shared with any professionals and only became clear in the criminal proceedings. The Review notes that ‘the overall presentation to the agencies was one of a happy and united family’.

It is clear that MSH was viewed through a ‘positive’ lens and there was nothing throughout the adoption assessment process that could have indicated MSH would injure and kill S. However, as the Review concedes, this ‘positive lens’ led to a minimisation of concerns about S’s injuries, 2 incidences of delay in getting medical treatment to her and MSH informing the HV he had sought GP advice about a bruise when he had not. The Review comments that ‘… with the benefit of hindsight, the monitoring and review of children placed for adoption can be strengthened by ensuring that safeguarding responsibilities are given due emphasis’.

The mother would have liked to have been part of that process to ensure that S was safe. But she was never given any opportunity.

The ‘Key Learning’ identified is set out at pages 14-15 – no discussion of failure to provide information to those who hold PR

- When children are seen at hospital, Paediatricians are key professionals in recognising the possibility of injuries being caused deliberately

- Professional judgements should be based upon consideration of all the evidence available rather than individual events

- Professionals need to ensure the details of a child’s injuries are recorded as significant events.

- Each agency has a professional responsibility to ensure that they are aware of all the significant events in a child’s life. – no one agency or worker held all the relevant information about S.

- Adoption reviews should provide opportunities for robust professional scrutiny and challenge – a holistic understanding of the child’s story was not gained

- The recording and retention of information received via text and other messaging services are an increasingly important source of information.

- Learning after S’s death – this was made more difficult by the fact that it was difficult to gather all the relevant information due to different IT systems in use and S being known by up to four different names.

I note again a failure to refer to the lack of provision of information to those who have PR.

The overall conclusion of the Review is that some systems and practices should be improved but that there was no information during the assessment stages of the parents that could or would have predicted what happened to this child.

This is true but rather skates over the concerns in the body of the Review that the significance of some of this information was missed; either because it was unknown (the second fracture) or because it was not seen in its proper context – serious bruising and delays in taking S to the GP for example. The reason for this is given as that the adoptive parents would inevitably be seen through a positive lens, as adoption is inevitably seen as a positive thing for a child. Thus as the Review concedes there was a ‘lack of professional curiosity’ regarding S’s experiences.

I am concerned about this. There were two categories of information that were not given to the mother.

a. information that S had been injured and suffered a fractured leg in the care of the adoptive parents prior to the making of an adoption order and while the mother still had parental responsibility (PR).

b. Information about S’s death which occurred after the making of the adoption order, thus extinguishing the mother’s PR.

Information withheld while the mother had PR

The mother was never told about her daughter’s injuries. The failure to inform her was a breach of her continuing Article 8 rights as a holder of parental responsibility. The local authority may argue that this breach would be seen as proportionate and lawful given regulation 45 of the Adoption Agency Regulations 2005, which disapplies section 22 of the Children Act 1989 and thus removes the local authority’s duties to ascertain the wishes and feelings of the parent and take them into account when coming to any decision about the child who is subject to a placement order. However, asking about wishes and feelings is not the same as providing information.

I do have to accept that it is likely that even if the mother had been told about S’s fractured leg, I do not think this would have made any difference to the LA approach as the significance of that injury was that there were in fact two fractures and the second was not found until after S died. I can speculate that if the mother had been told about the bruising and raised complaint, this might have pushed the various agencies into looking more closely at the overall picture painted by the bruising and late presentation to the GP. However, I suspect that absent any information that MSH was struggling to cope – which was not shared by MSH or his husband with any agency – that the mother’s intervention would have made little difference as there was no evidence before the LA to challenged the ‘positive lens’ though which the adoptive family were seen.

However, whether or not the mother could have ‘done’ anything with the information, I do not think is the relevant point here. She still had PR. She should have been told. Parents in this situation should have a remedy pursuant to the Human Rights Act for ‘just satisfaction’.

Is Article 8 ECHR extinguished after adoption? I don’t think so

After S’s adoption, the convention wisdom of the family courts is that all Article 8 rights fall away and thus the mother was no longer seen as anyone with any relevant interest in S’s life or death. This may be the current view of the courts –see Seddon v Oldham MBC (Adoption Human Rights) [2015] EWHC 2609 (Fam) but in my view it is based on a misunderstanding of what is actually protected by Article 8 – protection of family and private life encompasses protection of psychological integrity.

A sound mental state is an important factor for the possibility to enjoy the right to private life (Bensaid v UK para 47). Measures which affect the physical integrity or mental health have to reach a certain degree of severity to qualify as an interference with the right to private life under Article 8 (Ben-said v UK, para 46).

I imagine that the mother’s distress arising out the circumstances of her daughter’s death and the failure of other agencies to provide her with any timely information, would bring this case into the necessary degree of severity of harm. An adoption order did not change the fact that S was the mother’s daughter and at some point in the future, had she lived, may have sought her out. The pull of biology is recognised as strong and important for most and is reflected in such initiatives as life story work and the Adoption Contact Register.

If the law does says that the mother had no right to learn of her daughter’s death because an adoption order ‘wiped out’ her Article 8 rights, then in my view the law is wrong and should be challenged.

It is my very firm view that no law should be permitted to stand that is capable of imposing such a cruel situation upon any parent, no matter their previous failings and no matter that their child has been adopted. I suspect the problem here is what was identified by the Review at page 15: ‘the child while still legally a child looked after, was considered an adopted child and so this shaped the way professionals shared information.’