This is a post by Sarah Phillimore

Response of the CPR to the Family Inquiry into the courts response to domestic violence

I have commented critically on the nature of the Inquiry and the response of some such as Charlotte Proudman to what necessitates such an Inquiry – making the reasonable point that serious allegations require some kind of evidence.

I confess that I missed the initial call by a group of family lawyers into an independent review of how domestic abuse is treated in the family courts – reported here in Family Law Week on 29th May 2019 and here in the Guardian.

What happens when the starting point is ‘victim’?

The letter from the lawyers group is a detailed and clearly articulated statement of case that makes many good points. They say

There is no data collected about the implementation of Practice Direction 12J but anecdotal evidence suggests, as remarked by Lord Justice Munby in 2016, that there are very real concerns about its application in practice at different levels of the judiciary and across the country.

This echoes the points made by Dr Proudman in her post for The Transparency Project. I commented that her experience did not reflect mine, nor that of the other family lawyers who commented via Twitter. We clearly see here the dangers of relying on one person’s subjective experience over anothers – as the tiresome but accurate cliche has it ‘anecdotes are not data’.

But there is something interesting going on. The group states:

We can say from our experience that Practice Direction 12J is often ignored or ‘nodded through’ without any proper risk assessment, leaving women and children vulnerable. Where a fact-finding hearing is listed, the victim is increasingly being told to limit the number of allegations that can be considered by the judge, meaning that there is not a full forensic and expert assessment of the risks. The impact of coercive control, emotional abuse, economic abuse and other forms of non- physical violence are routinely overlooked.

And its there in that use of the word ‘victim’. Clearly if your starting point is that anyone who makes an allegation of abuse is in fact a victim of that abuse then you are going to take a very different and probably negative view of a judge who takes another approach – as indeed every judge must. To deal with any family case on the basis that one party’s allegations are accepted as fact prior to any attempt to hear evidence about contested allegations is simply a denial of justice. It is wrong. Advising police, for example, that they must commence their investigations by ‘believing the victim’ has been rightly decried by the Henriques Report and caused much human misery and massive waste of public money.

The fact that anyone who alleges abuse is automatically a victim is embedded in the recommendations

A domestic abuse coordinator in each court appointed in order to specifically ensure that victims going through the court process are properly protected and all necessary measures are in place, to try to minimise the risk of further abuse through the court process.

And this is a real problem. It is my very clear experience, arising I accept from 20 years experience, not robust peer reviewed research, that while out and out lies made by women about abuse suffered are rare, exaggeration and re-stating history are very commonplace. Unkindness, cruelty, blinkered thinking, denial etc etc are qualities that I am afraid are demonstrated equally by men and women. I do not doubt that violence in relationships is a real and serious problem and I do not doubt that the majority of physical violence is perpetrated by men against women. But emotional abuse, ‘gas lighting’, unreasonable behaviour are common to both sexes.

Many of my cases chart a drearily predictable course. I will represent a woman who makes a large number of allegations, often over many years. There will be nothing by way of corroboration from either the police or the medical profession. There will be nothing by way of statements from family or friends. The relationship with the father has utterly broken down; often he will contribute to this by behaviour which can be measured objectively as selfish and unkind. But when the allegations encompass drugging, rape, serious physical violence and there is literally nothing before the court but the assertion of the ‘victim’ that this is is so – what do the lawyers or indeed anyone expect the courts to be able to do with all this?

The group make the following suggestion for reform:

Training for the judiciary to better understand domestic abuse, particularly the nuances and subtleties of abuse such as gas lighting, coercive control, and financial abuse especially apparent when hidden by a polite, non-threatening perpetrator. Input from psychologists in this regard is key.

To which I make the following reply. Judges don’t need ‘training’ to know what violence is. They live in the world. They know what violence is. What they need is evidence on which to base decisions. The family justice system simply is not set up to offer inquisitorial tribunals to unpick relationships that may span decades and involve considerable amounts of ‘nuances and subtleties’.

Conclusions – we need the data

This polarisation of the debate into women = victim and men = perpetrator and everything must then stem from that, has done real harm. We can see this in the actiivities of such groups as Fathers 4 Justice. it is easy to dismiss them as posturing idiots but the anger they feel didn’t come from no where. To simply remove men from the debate – as the Panel membership appears to do, Mr Justice Cobb as the lone exception – is to fuel this kind of anger and distrust to the detriment of us all.

It is a great shame as I agree with and think very sensible many of the recommendations made by the group of lawyers. Removal of legal aid has caused enormous problems. Findings of fact need to be held far more often and far earlier. But I don’t accept the problems in the system are due to ‘lack of understanding’ from judges about issues of violence. They stem more from the very clear understanding by judges of their duties to the Rule of Law and procedural fairness. These are concepts vital to any society worth living in.

The real problem for the FJS is that our judges do not have the infra structure to support them to make speedy and robust decisions. I accept that cases drag on and there is little by way of support either during or after the court process.

However, without establishing a firm factual foundation for investigation, any proposed ‘three month’ inquiry into all of this is clearly doomed. Because we just do not have a consensus about what is really going on. Groups support women will say false allegations of abuse are very rare, groups supporting men say entirely the opposite. Just what is the evidence about the rate of false allegations and how do we find this data?

The group of lawyers say, rightly:

There is no data collected about the implementation of Practice Direction 12J but anecdotal evidence suggests, as remarked by Lord Justice Munby in 2016, that there are very real concerns about its application in practice at different levels of the judiciary and across the country.

What the group of lawyers recommend and I heartily endorse is this:

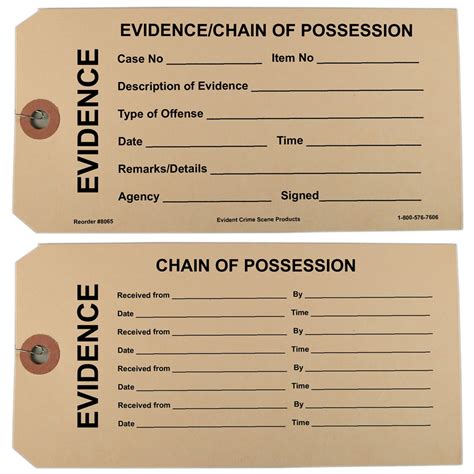

that robust recording of decision making is made by the Judge, and collated by an appointed court recording officer so that we can begin to assess the scale of the problem and so understand how we must deal with it.

This will be the only recommendation of the Family Inquiry that will make any sense at all. In my view. Nothing will change unless it can be identified and faced.