Thanks again to Kate W a retired social worker for her thoughts about the meaning of ‘likely to suffer’ significant harm. Consideration of the ‘risk of future harm’ is often a hot topic in debates about the child protection system; its detractors complain that this is no more than ‘crystal ball gazing’ and removal of children without actual proven harm is ‘punishment without crime’. What does Kate say in defence of ‘future risk’?

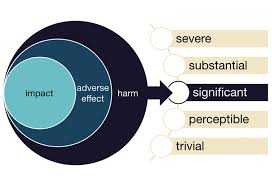

There appears to be a degree of confusion/misunderstanding about the meaning of “likely significant harm” Children Act 1989. The standard of proof needed is that the children IS suffering significant harm or is likely to suffer significant harm.

I can to some extent understand this confusion, as the wording can suggest that it is possible to see into the future and there is talk of social workers gazing into “crystal balls” etc. Very often parents involved in care proceedings talk of “future emotional harm” though significant harm covers all aspects of abuse and neglect. It would be difficult to argue that any child suffering abuse and/or neglect was not also suffering from emotional harm.

There are some cases where the issue of “likely significant harm” can be proven in court, and I provide some examples from my own experience below.

Case Studies – when parents just can’t cope

Case Study 1: D is a 25 year old single woman, pregnant with her first child. D suffers from schizoid affective disorder, a complex and enduring mental illness. She was diagnosed with the condition at the age of 18 years, though had suffered from mental illness since she was aged around 13 years. The illness from which D suffers is characterised by episodes of deep drug resistant depression and frequent psychotic episodes (as in not being in touch with reality) D hears voices that tell her god wants her to kill herself and she has made numerous suicide attempts by way of ligatures to her neck. She has been sectioned under the Mental Health Act on many occasions and is well known to the Mental Health Crisis Team and the emergency services.

D lives alone on the 10th floor of a high rise block of flats. She has no family support and her only friends are other flat dwellers, one of whom is allegedly the father of the child. However he is completely disinterested in D and claims that he is not the father of the child. He is a drug user and has criminal convictions. D is a heavy smoker, and a moderate drinker, and self harms on a frequent basis, almost always needing hospital treatment. The only support she has is a CPN (Community Psychiatric Nurse) who visits on a monthly basis to deliver medication. D rarely leaves the flat, only to buy essential items of food etc from a nearby shop. Neighbours sometimes shop for her and generally befriend her.

D is 28 weeks pregnant and refuses to access ante natal care though has allowed the health visitor to visit. D claims that she will be able to care for the baby. The HV does not share this opinion. The flat is very unhygienic, the floors are dirty and sticky, the only furniture is a very worn sofa; there is a TV and small table. The kitchen is dirty and greasy – there is a portable cooker and no fridge. The bathroom is dirty as is the bedroom. D has not collected any items for the baby and is dependent on state benefits and the flat is cold in the winter as she rarely has money for the electricity meter. In discussions D shows a complete lack of understanding of caring for a child, either practically or emotionally.

The psychiatric report states that D’s mental health condition will prevent her from giving good enough care to a child. The point is made that this may not be the case if there was a supportive partner and a good support network but this is not the case.

A pre-birth multi disciplinary case conference made a unanimous decision that the LA should make application to the court for an ICO on the basis that this baby is “likely to suffer significant harm” if left in the care of the mother.

D gave birth at 32 weeks to a premature baby who needed several weeks in the Special Care Baby Unit. D left hospital and didn’t visit the baby or show any concern for her child. The baby made good progress and was discharged and placed with foster carers at aged 3 months.

The court made an ICO and later a Placement Order. D did not contest the application, and the Orders were made by consent.

I would stress that it was in no way any fault of D that she was unable to care for her child. Indeed because of her severe mental illness she was barely able to care for herself and that given the extreme deprivation and poverty in which she lived, the care of a baby would have presented her with insurmountable difficulties and of course would place the child “at risk of significant harm.”

Case Study 2: This case concerns a couple who have lived together for 2 years. B (the female partner) and C (male partner). B has moderate learning difficulties and C has mild LDs. There are 2 children aged 2yrs and 8 months. C is not the father of the elder child. A social worker is allocated to the case and is in frequent contact with the family. The SW is concerned because C appears to be spending very little time at home and instead goes to the home of friends to play computer games. This leaves B alone to cope with the 2 children, which puts her under a great deal of pressure. A family support worker is allocated to the family and she visits twice per week and she too is concerned for the welfare of the children in B’s care. She has talked to C about the need for him to spend more time at home to help B care for the children, and despite his promises to do so this isn’t borne out in fact. C’s mother gives support from time to time but other than that, there is no support, although a neighbour “looks in” from time to time.

A nursery place for the 2yr old girl is being financed by CSs for 3 days per week. When C was part of the family he would take the child to nursery but since his absences, B is not motivated to take the child to the nursery hence the child only attends spasmodically. The nursery are concerned that the child is thin, often appearing dirty and smelly and unable to interact with the other children, preferring to cling to one of the adults.

There is growing concern that C is no longer living with B and the children and has in fact moved in to live with another young woman and her children. Initially B denies this but later admits that she thinks he is “not coming back.” The situation is deteriorating, and it is becoming evident that B cannot cope with the house and children. One day the neighbour contacts the social worker to allege that the 2yr old is screaming and B has shut her outside into the small yard. It is cold and the child is wearing only a vest and wellington boots. When the social worker visits a short time later, the child is in the house but C admits to shutting her outside because she was “getting on her nerves” – the child is still cold and distressed. C admits to smacking her to make her stop crying and is vague when asked what the children have had to eat that day. The baby is asleep in a pram and is suitably clad. During the visit C continues to shout at the 2 yr old and is threatening to shut her outside again and the child is crying inconsolably. It’s a grim picture and the social worker tells C she is not capable of caring for the children on her own. C immediately says “well you can take her – she’s a little shit…” the child is moved to foster carers under a S.20 on a temporary basis.

The issue of “likely significant harm” arises with the 8 month baby. He is of normal weight but very pale and has bad nappy rash. Again C cannot say what the baby has had to eat and there is no baby food to be seen in the house. C is disinclined to talk about the child’s diet other than to say he has a bottle of milk at bedtime but there is no formula to be seen, though there are feeding bottles which are dirty and have encrusted milk around the rims. The social worker asks C if there is any formula for the baby or baby porridge/jars etc and C says she doesn’t know but he can have some orange squash. This of course is not suitable nourishment for an 8 month baby. C is disinterested in the baby or his care but is very distressed about B leaving her, which is understandable, and is threatening to go round to the flat where he is living and leaving the baby with him. The social worker speaks to B on his mobile phone and he confirms that he has left C and has a new relationship. He does not want to care for the baby and claims that he is not the father. He is told about the EPO on the 2 year old and makes no comment, other than to say it’s a good thing as C is a “lazy cow who sits on her arse all day.” The SW asks if C’s mother will look after the baby and he says he doesn’t know but provides a telephone number, but she is totally unwilling to care for the baby or support C and repeats the claims that her son is not the father of the baby.

The social worker goes next door to talk to the neighbour who gives more information and states her concern that things have “gone downhill” since B left the family. Upon the social worker’s return to C’s home, she is half asleep on the sofa and the baby is wailing. She is refusing to give her consent for the baby to be taken from her. The social worker advises that she will have to seek an EPO on the grounds that the child is “likely to suffer significant harm” if he remains in the care of his mother. The EPO is granted and the baby moved to foster carers later that evening. He thrived in the care of the foster carers and was described as an “easy pleasant baby who ate and slept well.” C made very little effort to take advantage of contact offered to her whilst the children were with foster carers. However it was recognised by all concerned that C needed care and support for herself, given her moderate learning disabilities and this was provided by a social worker to some extent. It was an impossible task to expect that she could care for 2 young children when she was functioning as a child herself. It had been possible while B was in the family home as he was far more able than C and there hadn’t been any serious concern until he actually left the family.

Both children were later made subject to Placement Orders and adopted, though separately as it became clear that the 2 year old needed to be the youngest child in the family as she had clearly been immensely traumatised in the first 2 years of her life in the care of her mother and step father. This was manifested in some very difficult and challenging behaviours – and like many children who have suffered abuse/neglect, there was a significant gap between her emotional age and chronological age. Additionally she was also failing to meet her developmental milestones and there was concern about global developmental delay. The baby fared better as he had been with the mother and step father for a shorter time and so was much more able to form secure attachment patterns with his adopters.

Case study 3: this involved J (a young woman aged 18 years) who lived with her mother and younger brother. It was a very stable family and J enjoyed a close relationship with her mother and brother. Her mother reported that J was a quiet girl who had a few friends but was a “homebird.” Then J formed a relationship with a man (T) she met through a friend also in his late teens. J became pregnant very soon after the relationship started. Her mother was shocked and very concerned as she had no liking for T sensing a difference in her daughter, in that she seemed afraid of him although she denied this was the case.

The couple moved into a flat near to J’s mother’s home and the baby (M) was born but it was obvious from the beginning that the baby had physical disabilities – diagnosed as cerebral palsy of a severe nature. The young parents and J’s mother were distraught as can be imagined. J’s mother did all she could to support the young family and ensure that baby M got all the medical support that he needed. However a few weeks after M’s birth J told her mother than she was not to visit the flat again as T didn’t like her and thought her interfering. J said she would try and bring M to see her mother when T was out. J’s mother was a feisty woman (I’ll explain how I know all this at a later stage) and most definitely had J and baby M’s best interests at heart. She refused to abide by T’s rules and continued to visit the family as her concern for J and baby M was increasing. T would usually absent himself when she visited, slamming the door and telling her to F off.

J arrived at her mother’s house one day with baby M and she had a badly bruised eye and was shaking and crying, saying that T had “lost the plot” and she was terrified of him. Her mother immediately said that she and the baby should not in any circumstances go back to the flat. They were both welcome to stay with her and she would tell T not to come near her daughter again. But before this could happen, J took a phone call from T and immediately rushed back to the flat. This kind of event happened several times and J’s mother was very worried and frustrated that J was clearly dominated by T. When baby M was aged 6 months, T was bathing him and held his head under the water, gripping him tightly around the neck. J was hysterical and dialled 999 and M was taken to hospital and T arrested, claiming he was only playing with the baby.

However on examination baby M was found to have bruising and old fractures to both of his legs. T was later charged with grievous bodily harm and given a custodial sentence of 2yrs 6 months. Fortunately baby M survived and was hospitalised for 3 weeks. Obviously CSs were involved and were not satisfied with J’s account that she was not aware that T was harming baby M. They initiated care proceedings and placed baby M with J’s mother (baby M’s MGM) Contact between J and the baby was allowed x 3 per week but always to be supervised by J’s mother. J’s mother did not believe that J was unaware that T was harming baby M but she was convinced that her daughter was dominated by T and would therefore be unable to protect the baby.

J was adamant that she would have no contact with T in prison or when he was released but her mother didn’t believe her and was more or less certain that she was visiting him in prison. She challenged her of course, but she denied emphatically that she would have anything to do with him after what he had done to baby M. Apparently he had told J that he had done it as it was the best thing for a kid like that with twisted arms and legs and wished that he had drowned in the bath. J blurted this out to her mother but later denied that he had made such comments.

When T was released from custody J’s mother kept a close watch on the flat to see if T was visiting J as she believed this to be the case. Within 3 months of T’s release J became pregnant again but denied that T was the father. J’s mother immediately involved CSs and advised that she believed T was the father although she obviously had no proof of this. J’s mother began to visit J at the flat but there was no evidence of T. However one day J’s mother’s suspicion was aroused as J asked her not to visit that day as she was having a friend to visit with her baby. J’s mother kept a watch on the flat and decided to stand outside and wait to see if T went in or came out. She waited for over 2 hours and in the lobby area and finally saw T leaving the flat.

J’s mother “saw red” and as he ran off, she gave chase (she was a very fit woman, a hillwalker and strong swimmer) – he eventually jumped on a bus and the chase ended. J’s mother immediately contacted the social worker and the police (as T was on licence) and admits to slapping her daughter across the face, as she was so disgusted with her. J was apparently hysterical but her mother’s only concern was baby M. and the unborn child. J was trying to convince her mother and the social worker that T had only been in the flat for a few minutes to collect some belongings, but no one believed her, especially as her mother had stood outside the flats for 2 hours. I did ask J’s mother what she would have done had she caught T and she admitted that she didn’t know, as her anger had taken over!

There was a pre birth Case Conference and it was decided to initiate care proceedings on the basis that the unborn child was likely to suffer significant harm, given the injuries to baby M and the fact that J was still in a relationship with T and it was likely that T was the father. It was made clear to J that whether he was the father or not, she had been unable to protect baby M, given her fear of T and his controlling and bullying behaviour, and hence this unborn baby was at risk of likely significant harm. She eventually admitted that T was the father.

The baby girl was born and placed with J’s mother. She was made subject to a Care Order. J’s mother later successfully applied for SGOs on both children. I undertook the assessment initially for kinship care of the children and later for an SGO.

What do these case studies demonstrate?

I hope that I have been able to demonstrate in the 3 cases above exactly why that wording was contained in the CA89 “likely to suffer significant harm” and not because someone looks into a crystal ball and thinks “Oh they look like they might abuse or neglect that child in the future, so we’d better ask the court for an Order to be on the safe side.”

I don’t understand why so many people talk of the injustice of “future emotional harm” – I don’t see how emotional harm (be it in the present or the future) can be a “stand alone” reason to give as a justification for seeking an Order to remove a child. If a child is physically abused, sexually abused or neglected, then they are by definition going to be emotionally harmed – they can’t not be…………..can they?