This is a post by Sarah Phillimore. I am concerned that the decisions by Mr Justice Hayden in Re J [2016] are being overlooked in the ongoing debate about children who want to ‘change genders’, and in particular the role played by the Mermaids organisation. I discuss my unease about what would have happened in Re J if it was decided this year in a talk at the Make More Noise event on July 27th 2019

First disclaimer. I am not a bigot.

It has, and has always been my view from when I was very young, that if consenting adults wished to dress in a particular way, have sex in a particular way or get married to someone they loved who loved them back, that was absolutely their business and no concern of mine, other than to be happy for them that they had the chance to live their best life. As a disabled person I am well aware of those times in my life when I have been denied opportunities, been insulted or attacked for a physical characteristic that I did not ask for and was completely out of my control. I would never knowingly inflict that kind of harm upon another.

But I am also a lawyer. So by training and by temperament I am not interested in what people ‘feel’ about any particular issue. I am interested about what they can prove. What evidence do they bring to the table to support their fears or worries?

Some advice; if you find what I say ‘hateful’ and wish to have me removed from social media or my employment then of course you must take what ever steps you think are appropriate. But please remember I don’t have an employer; I am a self employed sole trader. If you think my words mean I am not fit to be a lawyer, please refer the matter to the Bar Standards Board.

Please also note that I will not agree with you and will use my best efforts to challenge and reject any complaints made.

Second comment. We cannot sacrifice facts for feelings.

In the on-going and harmful ‘debate’ about trans women with intact male bodies in female spaces (such as sports or prisons) we find very clear and horrible illustrations of what happens when people bring feelings to a fact fight; when both sides of the ‘debate’ appear to believe that they are supported by facts and reasons and the other by unreasoning hysteria and bigotry.

While adults may insult others as they wish, provided they don’t step over the line dividing freedom of speech from criminal harassment, I am concerned here about what is being argued on behalf of children. The need for clear and honest debate is particularly important when talking about the ‘rights’ of children to transition and to be supported/encouraged in accessing surgery or medication to do so.

i have no interest in controlling what consenting adults do to other consenting adults and think such attempts to control is a moral wrong, unless and until of course their activities impinge on my ability to live my life. However, as a lawyer who has worked in many years in child protection law, I do have a very keen interest in what adults do to children, often purporting to act in ‘their best interests’ when, to the objective outsider, it seems anything but.

Much of the increasingly anguished ‘debate’ about transitioning is now very clearly focused on children and at what age they could or should be supported to make the ‘decision’ to transition from ‘male’ to ‘female’ or vice versa. This ‘transition’ is often required to be supported by medication or pretty serious surgical intervention. The impact on the child’s body as he/she grows will be serious, often leading to infertility or loss of sexual function.

I have become increasingly concerned about the role played in all of this by the Mermaids organisation.

They describe themselves in this way:

Mermaids is passionate about supporting children, young people, and their families to achieve a happier life in the face of great adversity. We work to raise awareness about gender nonconformity in children and young people amongst professionals and the general public. We campaign for the recognition of gender dysphoria in young people and lobby for improvements in professional services.

The decisions in Re J [2016]

I am worried that the continuing debate and discussion over the role of the Mermaids organisation has overlooked a very important judgment from Mr Justice Hayden in July 2016 – J (A Minor), Re [2016] EWHC 2430 (Fam) (21 October 2016).

The Transparency Project wrote about the case and the media response here and summarised the court’s approach in this way:

Mr Justice Hayden heard the case over a number of days in the summer and, based upon the experts and professionals whose evidence he heard (along with that of the mother herself), the judge concluded that J was a little boy whose mother’s perception of his gender difference was suffocating his ability to develop independently – and was causing him significant emotional harm. He was placed with his father, where he quickly began to explore toys and interests that were stereotypically “boys”. The judgement is very clear that the father had brought “no pressure on J to pursue masculine interests” and that his interests and energy were “entirely self motivated” (pa 47). So, not forced to live “like a boy” (whatever that means) – but choosing (there is more detail in the judgment).

Importantly, Hayden J acknowledged that there are genuinely children who are transgender or gender dysphoric, and who present in this way from an early stage, but – and here is the crux of it – this child was not one of them. This was all about the mother’s position.

At para 63 of the July judgment, the judge commented on the expert opinion of the mother and how she presented:

When stressed and distressed, [M] becomes controlling, forceful and antagonistic. This reflects her underlying anxiety. She is actually very frightened and upset. She tries to sooth herself by taking control of situations but her interpersonal style is counter-productive. She does not negotiate well. She finds it difficult to compromise and situations become inflamed rather than de-escalated. In situations of interpersonal conflict, she protects herself from loss of confidence or face by unambiguously perceiving herself as correct which means that from her perspective, the other party is wrong. To acknowledge her flaws, even to herself, feels crushing and devastates her self-esteem so she avoids this possibility by locating responsibility and blame elsewhere. When she is unable to achieve the outcome that she wants, she resorts to formal processes and/or higher authorities: complaint procedures, The Protection of Human Rights in Public Law, the European Court of Human Rights, Stonewall and so on.”

It is clear that the mother was insistent with all agencies that J ‘disdained his penis’ and was being subjected to bullying at school etc. She could not provide any proof of this and the school denied it was happening. She was supported throughout by Mermaids who played a significant role in the development of a ‘prevailing orthodoxy’ that J – at 4 years old – wished to be a ‘girl’. That view was found by the court to have no bearing in reality and was a product of both ‘naivety and professional arrogance’

Mr Justice Hayden was highly critical of the local authority for getting swept up in this prevailing and false orthodoxy, commenting at paragraph 20 of the July judgment

This local authority has consistently failed to take appropriate intervention where there were strong grounds for believing that a child was at risk of serious emotional harm. I propose to invite the Director of Children’s Services to undertake a thorough review of the social work response to this case. Professional deficiencies to this extent cannot go unchecked, if confidence in this Local Authority’s safeguarding structures is to be maintained.

A later judgment in October 2016 dealt with the aftermath of the boy’s removal and how he had settled with his father and to what extent these matters should be in the public domain. That judgment is here: J (A Minor), Re [2016] EWHC 2595 (Fam) (21 October 2016)

What happened after 2016?

Mermaids at the time were highly critical of these judgments and said they would be supporting the mother in a appeal. No application was made to appeal. They showed no humility or understanding in their press release of October 2016, insisting that the courts simply had not understood issues of gender identity. I assert that no one can in good faith make such argument if they had bothered to read the lengthy and careful judgments of Mr Justice Hayden.

Since 2016 Mermaids have continued – in my view – to show no understanding or humility. The current controversy is around a grant to their organisation of £500K by the Lottery Fund which is currently under review and has been the subject of some critical press attention.

Children are – quite rightly in my view – protected as a vulnerable class of people in our legal system. Children below the age of 12 are highly unlikely to be considered to have the requisite maturity and understanding to make significant decisions about their lives that will impact well into adulthood. Even those older children who are ‘Gillick competent‘ may find that their wishes and feelings are not allowed to determine issues of significance; such as the right to refuse surgery.

The accepted wisdom of the majority of child psychologists is that a child under the age of 6 years is probably unable to express any view that does not align with his or her primary care giver. This is a relatively simple matter of stages of cognitive development and pure survival. The older a child gets the more their wishes and feelings carry weight, but they remain unlikely to be ‘determinative’ unless and until they age out of the protected class of ‘child’.

So why are we even entertaining any discussion that a 4 year old is in possession of all the facts and their consequences needed to make a serious decision about whether or not to keep or ‘disdain’ his penis? Particularly when organisations such as Mermaids and their supporters appear to wish to push for wholly regressive and offensive gender stereotyping such as little girls like pink and sparkly things and little boys want to play rough and get dirty. If a little boy wants to play with dolls and wear a dress, why does he have to ‘disdain his penis’ to do that?

What do we know about the implications of medical and surgical intervention for children?

Not only is a young child likely to be unable to grasp the necessary information to make an informed decision about transition, it seems that the adults around him or her do not yet even possess sufficient information to make a safe, informed decision on the child’s behalf. We appear to know more about the impact of puberty blockers on sheep than we do on children. Note comments from the Science Symposium on 18-19 October 2018 at The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, cited below in Further Reading. Grateful thanks to @bettytastic to alerting me to this.

We do know something of the effect of puberty blockers on the brain development of adolescent sheep however. Professor Neil Evans of the Institute of biodiversity in Glasgow reported impairments to several functions, including a sheep’s capacity to find its way through a maze, which persist after stopping puberty blockers. This raises questions about the possible neurological effects of puberty blockers on children’s psychological, social, sexual and cognitive development. Some of Professor Evans’s references are listed below (Robinson et al 2014, Hough et al 2017 a & b).

The consequences of a pathway of surgical and medical intervention are not merely physical of course. Stephen B Levine wrote in 2018 in the journal of Sex and Marital Therapy ‘Informed consent for transgender patients’ reminds us that risk needs to be identified across three categories – the biological, social and psychological. Four specific risks arise in each category.

Biological risks include loss of reproductive capacity, impaired sexual response, shortened life expectancy, Insistence that biological sex can be changed cannot alter the possibility of sex based illness – such as prostate cancer arising. Social risks include emotional distancing from family members, and ‘a greatly diminished pool of people who are willing to sustain an intimate and loving relationship’. Significant psychological risks involve deflection of necessary personal development challenges, inauthenticity and demoralisation – when changing your body does not bring about the desired changes to the way you ‘feel’.

Of course, the existence of risk does not mean that one should never embark upon a risky endeavour. It may well be that the benefits outweigh the possible disbenefits to a significant degree and the risk is well worth taking. But that conclusion cannot be reached without clear eyed and dispassionate unpicking of the risks AND benefits.

How can the ‘no debate’ platform and unquestioning acceptance of any child’s expressed wish to ‘transition’ ever reflect the serious ethical duty of medical professionals to be sure their child patient has offered informed consent?

To what extent are adult influences driving children?

Julian Vigo independent scholar, filmmaker and activist who specializes in anthropology, technology, and political philosophy, wrote for Forbes in December 2018 about discussions with Mermaids in 2013 and the concern noted then about what might lie behind adult desires for their chid to ‘transition’ – to help the adult ‘fit in’.

I spoke to Linda at Mermaids, a support group in London formed in 1995 by parents of transgendered children. She told me that this group supports parents who have children who do not ‘fit in’ with ‘gender roles.’ I ask what she meant exactly by ‘fitting in’ and Linda explains, ‘If you are a little girl who behaves like a boy, you will want to have your hair short, to play with the boys. Even at play group they will be different…they will be picked on and those are the problems.’ I tell Linda that many little girls will have short hair and play with boys—I was one of those little girls. She says, ‘I have known a lot of girls in my time and they don’t like rough and tumble..they don’t like playing with boys. They like to play with dolls, dressing up, playing in the Wendy House, to grow their hair…’ Linda emphasises that it is important that these children ‘fit in,’ a phrase she often repeats in our discussion. Is this what transitioning for some trans adults is about? Is this the ‘support’ that parents are receiving in order to understand ‘gender roles’?

Professor Michele Moore makes some similar points and her talk is linked to below.

Conclusions

I will never make any apology for raising and discussing these issues. As a disabled child who could not be ‘fixed’ it became clear to me in my teens that I had a choice; to kill myself or to try and live the best life I could in the body I had. I had virtually no support from the adults around me in this process; the 1970s and 1980s, when I grew up, were much less enlightened times than now and I am glad these issues can be more freely raised.

I wish for all the chance to the live their best life and to live it freely, with love and respect from their fellow humans. We should all do what we can to allow this to happen. If we can’t support it, we should step back and keep quiet.

However, we need to tread very carefully when it comes to little children, who are wholly at the mercy of the decisions made on their behalf by the adults caring for them. Any decision which has the consequence of setting their bodies and hence their lives on a particular path is one that must be taken carefully, honestly and in possession of all the facts. It should never be about a way of assuaging the pain or mental distress of any adult.

None of this means it is impossible for a four year old to have clear and decided views about what he or she wants to do with his or her body, or that it would be automatically wrong to act on those views. But it is – by simple matter of that child’s very young age and compromised cognition – highly unlikely that the vast majority of four year olds can make informed decisions about something serious – such as surgery. We need to be very, very careful about the extent to which adult hopes and dreams are pinned on children.

If anyone in the Mermaids organisation cannot read the judgments of Hayden J and feel appropriate remorse for their role in contributing to the significant harm caused to a 4 year old child, they are not fit to receive even 50 pence of public money, let alone £500K.

Edit 26th December 3.40pm

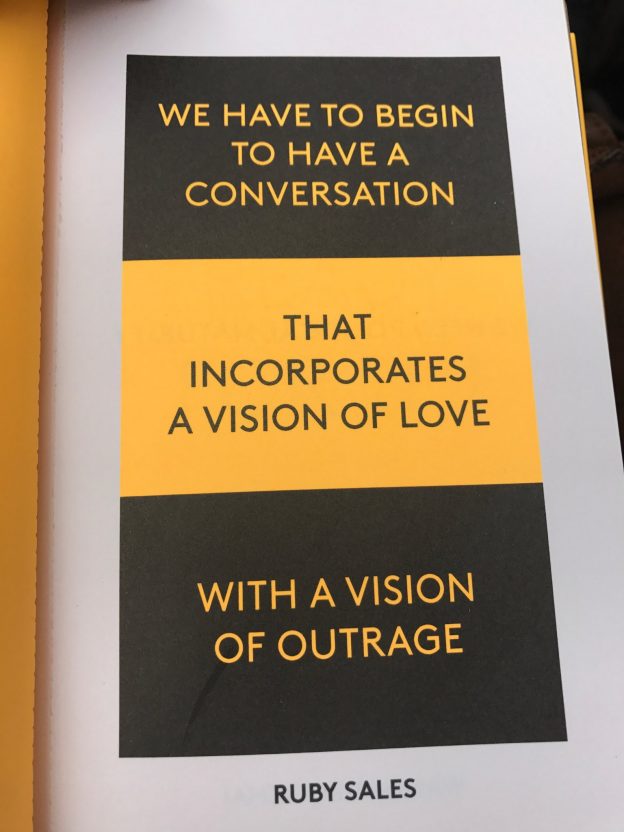

I am really grateful for the mostly courteous expressions of interest in this post. In particular, the comments from the parent of a trans child. I agree with her that this was not a case where anyone (so far as I know) was advocating for immediate surgery on a 4 year old. I remain very concerned about what the logical outcome for the child would have been if no one had intervened to disrupt the ‘disdain the penis’ narrative. But I accept that surgery and/or medication are not usually on the horizon until the child approaches puberty. I also accept – as did Hayden J – that there are children who will need the kind of support and intervention advocated by Mermaids. But to force ‘transition’ on a child who didn’t want it is as every much a horrible tragedy as it is to deny a child help and support they desperately need. The only way – I think – out and through these difficult and emotional questions is by adherence to facts and rational debate about them.

Second Edit 26th December 5.55pm

A reader comments that it is ‘absurd’ to say that re J highlights anything about Mermaids. I refer to this article in the Guardian which confirms that Mermaids supported the mother in court. I stand by my assertion that the judgment in Re J reveals very worrying things about Mermaids’ operation and assumptions. ‘To the man with a hammer – everything is a nail’.

Third Edit 1st January 2019

I have further edited this article to include references to some interesting papers and online talks which I have discovered in conversation with others on line. i remain profoundly grateful for the opportunity to take part in these kind of discussions.

Further reading

Articles/Research

A New Way To be Mad The Atlantic 2000

How common is intersex? Journal of Sex Research Dr Sax August 1 2002

Autopedophilia: Erotic-Target Identity Inversions in Men Sexually Attracted to Children November 2016 Psychological Science Journal

Mum of ‘gender non conforming child’ sells fake ‘extra small’ penises for transgender children under five – The Mirror December 2017

But nobody is encouraging kids to be trans! Lily Maynard March 2018

Emperor’s new clothes. Gender ideology and rebranding the privileged as the marginalised – Liberals for Sanity June 2018

,No, you don’t have a disorder. You have feelings – Lisa Marchiano July 2018

Those of us in the mental health profession ought to be in the business of helping people to see themselves as having the potential to be well and whole. We should help them understand themselves as resilient, rather than infirm and frail. We ought to help people imagine larger, richer, more complex stories for themselves, rather than simplistic narratives of illness and victimhood.

The Science of Gender: what influences gender development and gender dysphoria – summary of the 2018 European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology (ESPE) Science Symposium on 18-19 October 2018 at The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust. By Bob Withers and posted by Miranda Yardley in November 2018

Trans groups under fire for huge rise in child referrals – Andrew Gilligan November 2018

Young children, reality, sex and gender Katie Alcock May 2019

Politicised trans groups put children at risk, says expert – The Observer July 27th 2019

Talks/television

Rene Jax, a male to female transsexual, calls for caution and further research over use of medication for children who express gender dysphoria – Calfornia Family Council July 2018

Professor Michele Moore speaks in October 2018, discusses her concerns about the lack of debate about the impact on children of a medical and surgical pathway; that gender dysphoria does not reside in the body. Encouraging self identification in children is a tool of adult self interests. She is expert in Inclusive Education and Disability Studies

The Man who Lost his Body BBC 1997

Case law

Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority and another [1986]

Jay v Secretary of State for Justice [2018] EWHC 2620 (Fam) (08 October 2018) and note the evidence of Dr Barrett quoted at para 29 of the judgment:

“Separately, and recently, she reports gender identity problems. Her history, if taken at face value, is reasonably consistent with this diagnosis but the difficulty is that other aspects of that history are rather directly at odds with the documentary records leading me to have doubts about the veracity of her whole history – which would include a reasonably consistent history of gender identity problems. This aspect might be made clearer if a source other than [Ms Jay] could be interviewed …. If collateral collaboration is elicited I would reach an additional diagnosis of some sort of gender identity disorder. Whether the intensity of gender dysphoria caused by that disorder is great enough to merit or require a change of gender role might be explored in the setting of a gender identity clinic; it might be sufficiently intense in a prison but not so outside one and in civilian life, for example. If collateral corroboration is not convincingly elicited I would have grave doubts and wonder whether [Ms Jay]’s somewhat dependent personality had caused her to unwisely latch onto a change of gender role as a seemingly universal solution to both why her life had gone wrong and how it might be rectified.”

Lancashire County Council v TP & Ors (Permission to Withdraw Care Proceedings) [2019] EWFC 30

TT, R (On the Application Of) v The Registrar General for England and Wales [2019] EWHC 2384 (Fam) (25 – transman applied to be registered on child’s birth certificate as ‘father’ – refused as he remained ‘mother’ according to common law . This was appealed – the appeal failed. Apparently it will be taken to the Supreme Court.

https://twitter.com/VictoriaPeckham/status/1079039829604814849