Answering questions about adoption (by an adoptive parent)

A bit of background about me first – I’m a single mum, with three children, all of whom are adopted. Two of my children are now adults; the third is still in primary school. I spend a lot of time online nowadays, and I’ve been really privileged in the last few years to be able to talk with several birth mums about their experiences, and answer some of their questions about adoption and adoptive parents.

I could never truly know what it’s like to lose your child to adoption. But talking to mothers whose children have been adopted, has shown me that it’s often really confusing. They had a huge number of questions about adoption and adoptive parents, and no answers. They didn’t know any adoptive parents themselves, or at least none they felt comfortable asking their questions to.

I think these mothers were incredibly brave to ask me to answer their questions – they didn’t know me, I was just a random adoptive mum. They must have been worried that I would be judgemental or unkind. However it doesn’t matter to me whether someone is an adoptive parent or a birth parent or an adoptee. I hope I can find a way to support everyone who asks me to.

But I strongly feel that these mothers should have had an opportunity somewhere in the process to have all these questions answered, without having to reach out to a stranger on the internet. I am also sure that if these mums I talked to had questions, then there must be a lot more parents/grandparents (and other family) who also have the same questions about adoptive parents and adoption. So I’ve made a list of the questions I’ve been asked the most often by birth parents, and here are my answers. I’ve also included questions I’ve seen online which I haven’t been personally asked.

If you are a mother or father (or grandparent, sibling etc.) whose child (or grandchild, or sibling) is being adopted, then firstly I am sorry you are going through this. I hope you find these answers helpful. If you have any more questions you want to know about adoption that you think I could answer, please comment on this post, and I’ll try my best to answer for you.

And finally, from the bottom of my heart, thank you to the mums who asked me these questions first, who opened my eyes to how the process worked for them and who will remain in my thoughts always, as very courageous people who wanted the best for their children.

………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Why do adoptive parents want to adopt?

Adoptive parents have very different reasons for adopting. Many come to adoption following infertility, but quite a few of us don’t. For me, adoption was my first choice because above all, I wanted to become a mum and love a child with all my heart. I was a single lesbian woman and no other method of becoming a mother felt like the right thing for me to do. I felt that there were so many older children in care that I wasn’t comfortable creating a new life instead of becoming a mum to a child who was already here.

One thing all adoptive parents have in common is that we ALL adopt because we want to experience parenthood, in the same way that people who give birth to their children want to experience parenthood. I’ve seen a couple of people suggest that we want children as “accessories”, but nothing could be further from the truth. I want to reassure families of children in care, that with every adoptive family I’ve ever met, we love our children in exactly the same way as we would love a child born to us, and we would never treat a child any differently because they were adopted.

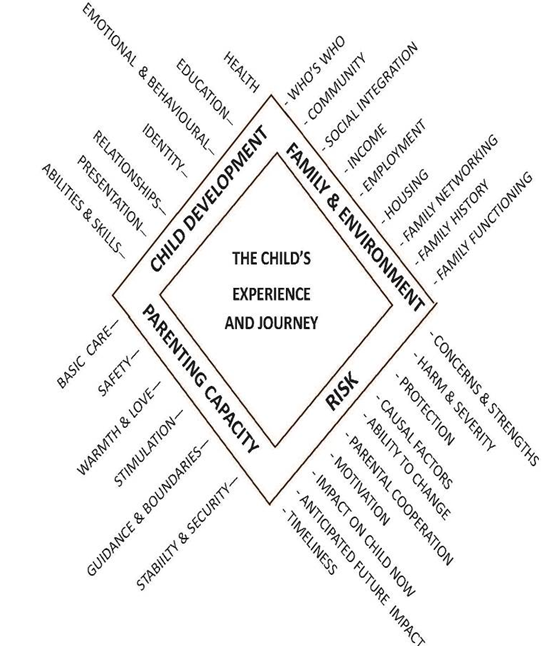

How does being approved as an adoptive parent work? Is it hard? Do they check up on you thoroughly?

It’s a long process, and it is definitely very thorough. It’s changed now from when I was approved to adopt, but the basics of it are the same. There are several key parts of it. Firstly, there are the basic checks – every adoptive parent will have a criminal records check (certain criminal offences bar you from ever adopting, including any offence against a child) and a medical check to make sure they are well enough to parent a child into adulthood. Social services will also check on prospective parent’s finances, inspect their home and make sure it’s safe for a child, and also get references from family, friends and others. For instance, my employer had to give a reference for me when I adopted the first time.

Secondly, there is a “preparation group”, which all prospective parents will attend at some point during the process. The point of this is to educate, and prospective parents will be taught about the legal process of adoption, why children are available for adoption, about parenting adopted children, and so on.

Thirdly, there are the homestudy visits. This is where a social worker visits the parent/s in their home and talks to them in huge depth about their life and about adoption. For instance, in my homestudies, we talked about my childhood, my family, what support I have around me, my beliefs, my previous relationships (including my sex life), how I would support and parent my adopted child, and about what kind of a child I would be adopting. We basically give social services our life story! A social worker even interviewed one of my ex-partners as part of my assessment.

The social worker who is assessing us will write all this information into a big report. Lastly, the report goes to an Adoption Panel, who review it all, and then recommend whether a parent should be approved to adopt or not.

So it is definitely a thorough process, and whoever adopts your child, will have been checked, questioned and scrutinised as far as possible to make sure they are up to the task.

Do you pay social services to adopt a child?

If we are adopting a child in the UK care system, no we don’t, absolutely not. Not even one pence! You might see people at some point claiming that we pay social services for a child, but this is not true at all. I think some of this confusion is because people see American adoption sites online, and over there, they also have a private adoption system for babies where money is paid by adoptive parents to the adoption agencies. This just doesn’t exist in the UK, so don’t let those sites worry you.

Do you pay any money to anyone else to adopt?

All adoptive parents have to have a (thorough) medical check. Doctor’s surgeries will usually charge for this, in the same way as they might charge for holiday vaccinations or some medical letters.

At the final part of the process, when you apply to the court to legally adopt your child, the court charges a fee. Some adoptive parents have to pay the fee themselves, but sometimes social services pay it for them. I have never paid for the court application for instance; the council have always paid it for me.

There is no other money paid to anyone in the adoption process.

Do you get paid to adopt?

No. Adoption is very different from foster care. Foster carers get paid a weekly allowance to foster. But when you adopt a child, they become your child (legally the same as if you gave birth to them) and so you are entitled to the same as birth parents get for their children (child benefit for instance).

What information do you get given about a child by social services, and what makes you “make your mind up” to adopt that child?

We get a lot of information. The very first thing we see is usually a short profile with just a little bit about the child, and if we are interested, we would get a lot more, in a report which is now called a CPR (Child Permanence Report). The information would include – about the child’s background, their birth family, why the child is in care and being adopted, the child’s personality, interests, behaviours, their health and medical information, their development, if they have any ongoing difficulties or need to be parented a bit differently to other children, about school and friends. It will also say what the plan is for contact after adoption with birth family.

After that, if you are still interested in adopting that child, the child’s social worker reviews your homestudy report and interviews you. Then they (and other members of their adoption team) come to a decision about whether they want to take things further. So it’s not just about you, as a parent, picking out a child. We adoptive parents do not just select a child to adopt like how it was decades ago. Social services have to choose you, based on whether they think you are the best possible parent for this child, and whether you can give this child everything they need.

If social services choose you, you then get even more information. You will meet the foster carer/s, and a medical advisor/paediatrician to get as much information as possible about the child and get all your questions answered. Finally after this, another ‘panel’ approve the match. This whole process of ‘matching’ lasts several months.

Making up your mind that you would like social services to choose you for a certain child, is really different for different people. Some parents ‘just know’ as soon as they read the CPR report, but others don’t and need more time.

When I read my eldest daughter’s information, I felt a strong connection to her, and I felt once I’d read her reports that she was most likely my daughter. I can’t tell you why I felt such a strong connection, it just happened! But we always use the huge amount of information we have to make up our minds as well. We have to be certain we can be the parent this child needs, and that we are comfortable with the child’s behaviour and their needs.

Whoever your child/relatives adoptive parents are, they will have put a huge amount of thought into whether or not to adopt your child/relative, and considered really carefully whether they are the right parents for this child.

Does eye and hair colour come into it?

No! I’ve seen birth parents being told that adoptive parents want children with blonde hair and blue eyes. Actually, we generally couldn’t care less what our child will look like! I’ve certainly never met any adoptive parent who cared whether their child was a blonde, or a brunette, or whatever. We view our children the same as we would a birth child. We wouldn’t care what our birth child looked like, and we don’t care what our adoptive child looks like. We just love them for who they are on the inside.

Personally, I thought it might be helpful for my children, if they looked like I could have given birth to them, because then my children could have privacy – they’d never have nosy strangers thinking ‘ooh, she/he must be adopted!’ based on their appearance. So for me, it was all about the child, and what I thought would be good for my child. It was not about me. As it happens, all my children look quite different, even the two who are birth half siblings!

Do you meet the child before you’ve decided 100% [if you want to adopt them]?

No. Being introduced to the child you are adopting is the very last stage. It’s called “introductions” and it’s where you and the child get to know each other before the child moves in. Before that happens, you’ve had all the information, made up your mind 100%, and been to the panel that’ve approve the match (and of course you’ve bought furniture and decorated etc.!) At this stage, everything is set. Once you’ve read the CPR and been to panel etc., you can’t meet the child and then decide if you want to adopt them. That would be very unfair and wrong for the child. As far as I was concerned, as soon as my children were told about me for the first time (by their foster carers and social worker) then I was absolutely 100% committed to them.

Do you “have” to tell the child that they are adopted? Could it happen that an adoptive family wouldn’t tell the child?

You don’t “have” to tell, because there is no law about it. We have the same freedom as birth parents to tell or not to tell our children about their early lives.

However, it is very rare nowadays for a child not be told they are adopted. Right from day one, we are told how important it is for children to know their story. Social workers and other adoptive parents, we are all very clear to prospective parents about how important it is for children to know about their adoption in an age appropriate way. Parents can access a lot of advice and tips about how best to do this. So whilst it could be that a child wouldn’t be told, it’s very unlikely. I’ve only come across a couple of people in about 18 years who haven’t told their children (and this includes online as well), as opposed to hundreds and hundreds who have.

At what age do you ‘tell’? And how?

Obviously with an older child, they know what’s happening. With a baby or toddler who is too young to understand, the way most adoptive parents try and ‘tell’, is in a way which means the child ‘always knows’. When they are older, they shouldn’t be able to remember a time when they didn’t know they were adopted. This means that for most children adopted as babies, they’ll be having little conversations about adoption by the age of 4 at the latest, but most usually a bit younger than that.

I told my youngest child the story of “the day we met” from when he was 2 years old (and he was 23 months old when we met), and I was also mentioning the word ‘adoption’ from that age. I didn’t bombard him with information; I just dropped in little things here and there. For instance, I remember when at age 3, a neighbour of ours was pregnant, and he pointed at her because she was getting so big. I said that yes, babies grow in the womb which is down in your tummy area, and you grew in X’s womb before you came to live with me. And he repeated that back to me.

All children who are adopted now are supposed to have life story books. These books, which as the name suggests, tell the child’s life story, might help parents to explain to the child the basics.

What are the options for any contact with birth mum? What’s the “norm”?

The norm in my experience is letterbox contact, which means letters going between you and the adoptive parents. This is normally either once or twice a year. It isn’t so common for there to be visits, but if there are, it will most likely be either once or twice a year. I’ve personally done both letters and visits.

For other adult family members, there might also be letterbox or, less commonly, visits.

The plan for contact should be mostly decided on before the child moves into their adoptive home, although it isn’t always. There may be a letterbox agreement which you sign and the adoptive parents sign. This agreement would say when the letters are being sent, to whom, how they are signed, and so on.

As the child gets older, they can have their own say in contact. For instance, my youngest child has asked for all letters to be stopped, so I stopped them. On the other hand, if my child had wanted the opposite and wanted more letters, I would have tried my best to add in another couple of letters a year. For adoptive parents, it’s about supporting our kids and helping them process everything.

What are the options for any contact with siblings? What’s the “norm”?

It definitely depends on where the siblings are living, whether they’ve lived together before and how close their bond is. But in my experience, visits with siblings are much more common than visits with any other members of the child’s birth family, especially if the siblings are also adopted or in long term foster care. I’ve supported my kids through a whole lot of sibling visits over the years. However, if there are no visits, letterbox contact is very often in place for the siblings, usually 1-3 times a year.

Will my child be told that I love them?

I realise how desperately you want your child to know that you love them. Every adoptive parent speaks to their children differently about their past, but most parents, when talking about their (young) child’s birth family, choose to say something along the lines of “your birth mum loves you very much, but can’t look after you”. As our children get older, we add in more about the ‘why’. I certainly have told my children that they are loved, and all the other adoptive parents I’ve met, tell their children the same. I want my children to know that they are loveable people, were the most loveable babies in the world, and that nothing that happened is their fault. I certainly want them to feel loved, and that’s something that all adoptive parents want for their children.

Will my child’s name be changed?

This is something I can’t give an answer to, because every situation is different. I can only say that in nearly all situations, the surname will be changed. Some children have their first names changed, but others don’t. Some of the things that may go into the decision are – whether there is a security risk (whether the child is likely to be recognised), how unusual the name is, its meaning and how old the child is.

I can give you my situation as an example – two of my children were older children when they came to live with me, hence it was entirely up to them what they did with their names. My eldest literally waltzed downstairs one morning and informed me that she was dropping both of her middle names, and had picked two new middle names for herself instead, which were x and y! And that was that, as far as she was concerned. My middle child on the other hand, only ever changed surname, and has kept all her other names as they always have been.

However my youngest child has been entirely named by me (and themselves!). I changed my child’s first name for many reasons, chief among them a security risk from a few people. I kept the old first name as a middle name, because I couldn’t take that away from my child. However, recently my child asked for that (original first) name to go entirely, and to pick a new middle name instead. So I went with my child’s choice, and we picked a new name together, which we are in the process of making legal now.

We are just one family, and every adoptive family will have a different story. So I can’t say whether or not your child will be given a new first or a new middle name. However I can say that if your child’s name is changed, they will at some point be told about it. My youngest always knew which name was originally the first name.

Again, if you have any more questions you want to know about adoptive parents/adoption that you think an adoptive parent could answer, please comment on this post, and I’ll try my best to answer for you.