This is a post by Sarah Phillimore.

I was interested to read the decision of Re S (Parental Alienation: Cult), a judgment handed down on April 29th 2020. It covers so much of what has been interesting and challenging for me throughout my career. The damage that even loving parents can do to their children, and the particular harm caused by a parent who puts their own right to self identification above the child’s welfare.

This is a case about a mother who was a member of a cult and a father who wanted their daughter to live with him because he was so worried about her exposure to the cult. His application was refused and the child’s time was divided between the parents; he appealed.

The first Judge to hear the case agreed that the mother was a member of a cult organisation founded in Australia in 1999 by Serge Benhayon, called ‘Universal Medicine’. The mother in turn cross appealed, denying she was a cult member and sought to reduce the amount of time the child spent with her father, relying on historic and repeated allegations that the father had sexually abused the child and he was coercive and controlling.

The father’s appeal ultimately succeeded.

The judgement offers a helpful analysis of the law relating to the weight to be accorded freedom of belief when that conflicts with a child’s welfare. I think it poses some interesting further questions about what areas courts ought to be investigating when faced with other parental systems of belief that are controversial or deny material reality – such as the growing insistence in some quarters that biological sex is a myth and to attribute it to a child is some kind of hateful bigotry.

The law concerning freedom of belief

The court first needed to examine the law concerning freedom of belief. The first Judge carefully surveyed the law’s treatment of sects, cults and minority groups in cases involving children. He recognised that the court had to approach this with caution: the court should not become unnecessarily involved with criticising minority groups and controversial beliefs. The court should only be concerned with the welfare of the child.

The leading decision around religious upbringing is Re G (Education: Religious Upbringing) [2012] EWCA Civ 1233; [2013] 1 FLR 677. This case involved the schooling of children from an ultra-orthodox Jewish background, but the comments of Munby LJ apply equally to belief systems that are not avowedly religious. The Judge is not there to weigh one religion against another and all are entitled to equal respect so long as they are ‘legally and socially acceptable’. The court must recognise Article 9 of the European Convention:

“1 Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief, in worship, teaching, practice and observance.

2 Freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs shall be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of public safety, for the protection of public order, health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”

From this, we can see the right to religious freedom is not absolute but qualified in two ways. Your religion or philosophy is protected only if worthy of respect in a democratic society and not incompatible with human dignity – see Campbell and Cosans v United Kingdom (No 2) (1982) 4 EHRR 293. Second, how you ‘manifest’ that religion or philosophy – such as in worship or other observance – can be restricted if necessary to protect the rights and freedoms of others.

It is incompatible with any power on the State’s part to assess the legitimacy of religious beliefs; the State must be neutral and impartial – see Moscow Branch of the Salvation Army v Russia (2007) 44 EHRR 46.

But if a religious practice or belief has negative consequences for a child’s welfare, the court has the power to restrict manifestations of that practice or belief – and in the most extreme cases, remove the child from the care of the parent who will not change their views.

In summary, the court must respect the mother’s beliefs to the extent that the teachings of Universal Medicine are worthy of respect in a democratic society, but the child’s welfare remains the paramount consideration and may override the mother’s rights.

The law concerning parental alienation

The Appeal Court then considered the law around parental alienation. The Court rejected any attempt to enter the debate about labels, agreeing with Sir Andrew McFarlane (see [2018] Fam Law 988) that where behaviour is abusive, protective action must be considered whether or not the behaviour arises from a syndrome or diagnosed condition. The Appeal Court relied upon the CAFCASS definition of alienation.

“When a child’s resistance/hostility towards one parent is not justified and is the result of psychological manipulation by the other parent.”

Such manipulation does not need to be deliberate or malicious. It is the process that matters, not the parent’s motive.

The Appeal Court commented:

Signs of alienation may include portraying the other parent in an unduly negative light to the child, suggesting that the other parent does not love the child, providing unnecessary reassurance to the child about time with the other parent, contacting the child excessively when with the other parent, and making unfounded allegations or insinuations, particularly of sexual abuse.

These cases can be very difficult but the courts are under a positive obligation imposed by Article 8 of the ECHR, to strive to find some resolution, particularly as the passage of time often leads to a determination of the matter by default, as a child simply hardens negative views towards the absent parent.

As McFarlane LJ said in Re A (Intractable Contact Dispute: Human Rights Violations) [2013] EWCA Civ 1104; [2014] 1 FLR 1185 at 53:

The conduct of human relationships, particularly following the breakdown in the relationship between the parents of a child, are not readily conducive to organisation and dictat by court order; nor are they the responsibility of the courts or the judges. But, courts and judges do have a responsibility to utilise such substantive and procedural resources as are available to them to determine issues relating to children in a manner which affords paramount consideration to the welfare of those children and to do so in a manner, within the limits of the court’s powers, which is likely to be effective as opposed to ineffective.”

The courts have to keep the child’s medium to long term welfare in mind, as the temptation may well be to take the short term path of least resistance as less stressful for everyone. However the court must not wait for serious harm to be done before taking appropriate action.

The Facts

The parents separated in 2012 when the child was about a year old, so at the time of the appeal hearing, she was aged 9 years.

The father moved out but continued to spend time with his daughter on alternate weekends. About the same time as the separation the mother became a ‘student’ of ‘Universal Medicine’.

The Judge did not need to decide if this was a ‘religion’, but found it was a ‘belief system’ to which the mother was strongly aligned. The founder of this system, Serge Benhayon, was described by an expert on cults, the Rev Dr David Millikan, in this way:

Benhayon hovers over his followers with a myriad of pronouncements about how they should behave. His teachings, cloaked in the robes of sanctity, prescribe what food they can eat. He has strict rules on clothes, work, physical exercise, how to speak and move, how sex works (he encourages orgasms like a hermaphrodite), how to treat children, how to dispose of their money, what books to read, who to talk to, what media to read or watch, how to treat family and friends who complain about their discipleship. Piece by piece their lives are recast in the mode of Benhayon himself.”

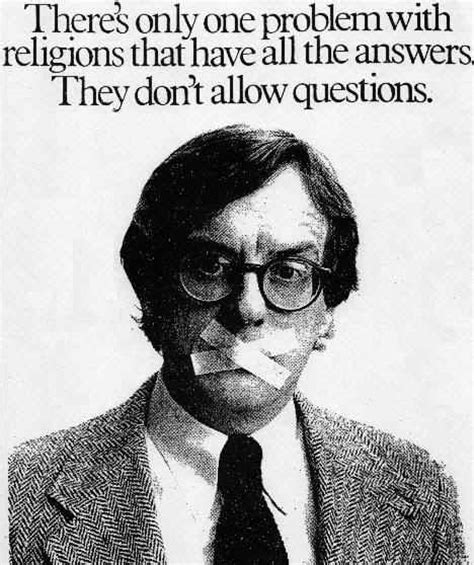

As is common with cults, its members will lose the capacity to question what they are taught and will consider those outside the ‘closed system’ as unable to understand. Relationships with family or friends who aren’t in the cult becomes very difficult, or are severed entirely.

The father was particularly concerned by the attitude of the cult towards food, collecting information which showed what categories of food were allowed or disapproved of by Universal Medicine. The categories include “Fiery foods”, “Pranic foods” (said to hinder the flow of the light of the soul and the body, including all wheat and grain and dairy milk … ) and “Evil foods”.

Other concerning cult practices included “Esoteric ovary massage” which is said to offer women “a true healing to deconstruct the emotional inputs and blockages that may lay suppressed in the ovaries, consequence to the many experiences a woman has endured throughout her life that have had the effect to the relationship she holds with herself”. There is apparently no evidence in support of any of the cult’s practices which were ‘developed’ by the cult founder Benhayon, described as a ‘former bankrupt tennis coach from New South Wales’.

When his daughter was three, the father became increasingly concerned about her restricted diet and the influence of this cult upon the mother’s parenting. The local authority assessed and found a good relationship between mother and child. The social worker thought the mother’s ideas were somewhat ‘fixed’ but did not pose a safeguarding concern.

The father applied for a child arrangements order so that his daughter would share time equally between her parents and a specific issue order so that she would not have any further dealings with Universal Medicine.

The mother objected, and asserted that that Universal Medicine was not a cult but rather “an award-winning complementary healthcare organisation bringing many benefits to its adherents, herself included.”

“Serge provides the absolute reflection of integrity and truth,and of unwavering love for all in service untiringly andunceasingly… No greater role model have I ever met.”

CAFCASS reported in April 2017 and recommended that the child should not attend any Universal Medicine events until she was old enough to make informed choices, reporting concern that the child would become segregated and that would impact on her formation of relationships.

The parents were able to agree shared care and the mother was prohibited from taking the child to UM events before she was 16, imposing any teachings or doctrines or initiating discussions about UM.

By July 2018 the father was concerned that the mother was not sticking to this agreement and in fact the influence of UM over their child had increased.

In October 2018 an Australian court [Benhayon v Rockett (No 8) 2019 NSWSC 169] found that Universal Medicine was a socially harmful cult and Benhayon to be a sexually predatory charlatan who had assaulted female students and had an indecent interest in children as young as ten.

The father therefore issued his application for his daughter to come and live with him and have no further involvement with the cult. The father set out a schedule of allegations against the mother. In May 2019 the court refused the father’s application for a psychological assessment of the child but ordered a report from an Independent Social Worker. The matter was listed for a three day final hearing in November 2019.

The father said that he did not trust the mother to distance herself from Universal Medicine and although their daughter would be devastated to spend less time with her mother, to remove her from the mother’s care would be the lesser of two evils.

The mother rejected the father’s criticisms of Universal Medicine and alleged he was coercive and controlling. The Independent Social Worker found that the mother’s involvement was harmful to the child, in terms of restricted diet, behaviour and beliefs. She recommended that the child live with her father and have supervised contact with her mother.

The mother then changed her legal team and instructed her new lawyer to strike out the father’s application altogether on the grounds that any transfer of residence would breach the mother’s Article 8, 9 and 10 rights. This application was dismissed and the matter continued to trial. The mother asserted that the Australian judgment was nothing to do with her and it was discriminatory to require the child to give up her ‘thoughts and conscience’.

The Judge’s Decision and the Appeal

The Judge rejected any allegation that the father was coercive or controlling. He was motivated by concern for his child’s welfare. He thought the mother seemed genuine in her agreement to dissociate herself from Universal Medicine if it meant her daughter would stay with her.

Both parents loved their daughter and could meet her practical needs. The Judge concluded that the order which would best meet the child’s welfare was a return to the arrangements in 2017, after weighing up the harm presented by Universal Medicine against the distress that the child would feel if spending less time with her mother. The court was persuaded that the mother was ‘sincere and genuine’ in her assertions that she would ‘modify’ her thinking about Universal Medicine.

The father appealed, on the basis that the Judge had given inadequate reasons for not following the recommendations of the ISW and that by January 2020 it was clear that the mother was backtracking from her undertakings and that the child arrangements order had already been wholly disrupted.

The mother responded to seek a reduction of the father’s time with the child, on the basis that historic allegations of sexual abuse had not been properly investigated and that the mother could not be asked to give up her her beliefs.

The Court of Appeal rejected the mother’s cross appeal and found that the Judge had been entirely correct in his evaluation of the facts and that Universal Medicine was a harmful cult. What was at issue here was his evaluation of how this applied to the child’s welfare and what orders should be made. It was clear that the mother was not going to stick to her undertakings. She had raised issues of sexual impropriety against the father since 2015. This supported the father’s case about parental alienation but had not been considered by the Judge.

The court therefore decided to give the mother one last chance to demonstrate that she would reject any adherence to the cult, failing which the child would move to live with her father. The final hearing was listed for July 2020.

EDIT On 15th July 2020 the court decided that the child should move immediately to her father’s care, as the mother was not able to show that she had made the necessary break with the cult. See Re S (Parental Alienation: Cult: Transfer of Primary Care) [2020] EWHC 1940 (Fam)

Conclusion

This case is a fascinating example of parental alienation but also a very useful examination and summary of the authorities relating to freedom of religious or philosophical belief and how rights can exist in serious tension with one another.

The mother has a right to religious freedom. But equally her daughter has a right to a healthy diet, to grow up to make her own choices and to have a relationship with her father. The court found that the child’s right to be free of a ‘harmful and sinister’ cult outweighed the mother’s right to continued adherence to it. However the mother would be given one last and short chance to show she could break away from the cult and promote her child’s welfare.

I wonder what parallels can be drawn between this case and the continuing debate about ‘transgender children’. Is there really much distinction between a harmful cult that puts food into categories (including ‘evil’) and promotes ‘esoteric ovary massage’ and a belief system that holds that biological sex does not exist but rather we can chose from infinite ‘genders’?

Both are products of adult minds. Neither have any foundations in fact. Both, if imposed on children from a young age have the potential to do harm. The welfare of the child remains the paramount consideration and that will require clear, honest and thorough weighing of a variety of factors in every such case.

Further reading

In whose best interests? Transgender Children: Choices and Consequences

No one, no issue is off the table when it comes to safeguarding

You had better make some noise – abusers will exploit bad laws and poor safeguarding